Samuel Andri says the church should be challenging itself at least as much as the government.

On Palm Sunday morning, while I was speaking to my small group about the readiness of Jesus Christ to face His death (Mark 15), one of the older youths suddenly broke into tears.

She then explained that that particular gospel story somehow made her think of her grandmother, who is seriously considering euthanasia – often referred to as Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD).

As the primary caregiver for her grandmother, she felt like she had failed her. On one hand, she knew that her grandmother is suffering physically and mentally. Yet on the other hand, she still could not understand why, after all of her best effort to care for and to love her, her grandmother would still consider euthanasia.

Now, I am well aware that voluntary euthanasia or MAiD is an extremely complex and multi-faceted issue that directly affects people who are most vulnerable, i.e., the sick, the disabled and the frail. In this sense, I concur that they are the ones who should have the biggest say on this issue.

Indeed, I have no intention to offer another ethical argument for or against euthanasia. There are already numerous sophisticated ethical arguments representing both positions.

What I want to reflect upon here, instead, is something that I have been pondering since that emotional discussion on Palm Sunday morning – that is, how did we arrive here? How did we become a society in which it is conceivable – and even considered compassionate – to alleviate people’s suffering by giving them an option to kill themselves?

To put it bluntly, how did our society become so convinced that active, voluntary suicide could be the best option to relieve certain human sufferings? What kind of social formation and/or habituation took place in our society that makes the legalization of MAiD not only possible but also widely supported?

Furthermore, since my pondering upon this pressing issue has been interrupted by the two most important events in the Christian liturgical calendar – Good Friday and Easter – I cannot help but ask myself: in what way could the church’s proclamation of the death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ meaningfully re-form and re-habituate our society’s perception of death and dying in relation to MAiD?

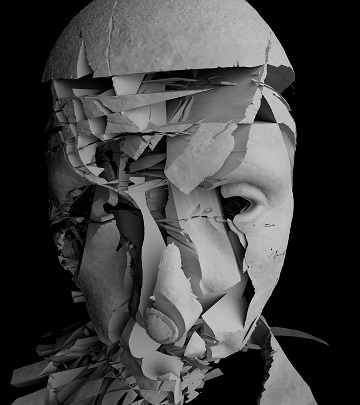

The meaninglessness of death in secular Western societyi

Image by Wendy Scofield

If we want to deeply understand the radical change of attitude toward euthanasia, we need to first understand the change that happened before that, which is our society’s change of perception toward the meaning of death.

Unlike in the past or in other cultural locations, death has become a meaningless event in our secular Western society. One could strongly argue that this meaninglessness of death is a direct result of our society’s insistence on excluding any reference to transcendence. Let me explain.

With the rise of science, our secular Western society reduces our perception of reality only to what can be measured by scientific reasoning alone. In other words, no more room for anything beyond this material world. The world becomes ‘disenchanted’ – to use Friedrich Schiller’s characterization of the secular West.

Therefore, our attempt to discover the meaning of life is constricted to this enclosed, material universe alone.

How then could people discover meaning in this utterly enclosed secular world? Ultimately, one’s meaning can be found only through one’s positive contributions for the common benefit and the flourishing of the wider society. Here, personal freedom and liberty are assumed and upheld as long as we keep bringing mutual benefit for the flourishing of society.

It has become inevitable that the perceived value of humanity becomes increasingly instrumental and economic. Hence, it comes as no surprise that people relentlessly pursue productivity and efficiency in all aspects of their lives. We regard our lifespan as an opportunity to construct our own meaning and values through various activities that benefit society.

Death then becomes nothing but a meaningless tragedy. It can only be understood as the very event that ultimately impedes secularists’ pursuit of progress toward human flourishing. It becomes “the terminator of purpose, the dreaded force that wipes out human effort in attempting to make life meaningful.ii” Death strips off a lifetime’s worth of self-constructed meaning.

Escaping limitation

Image by Eric Butler.

Considering the fact that death no longer has meaning, that one’s value and meaning in life are ultimately derived solely from one’s contribution to the progress and the mutual benefit of society and that productivity and efficiency become the chief goal in secularists’ pursuit of progress, it is nearly inevitable that our society would be favourable to euthanasia for the sick, the disabled and the frail.

For what prospect is left for the sick, the disabled and the frail within a society that deifies progress more than anything else? No wonder many choose to quickly escape from their profound pains and agonies through euthanasia or MAiD.

Indeed, by giving the option only for the sick, the disabled and the frail to actively and voluntarily end their lives, secular society has in effect declared that these human beings are more disposable than the strong, healthy and productive ones.

The value of human beings has been reduced solely to their ability to contribute to society’s progress. I cannot help but wonder whether this is why euthanasia has often been portrayed as an act of undertaking death with ‘dignity’ – as if one’s suffering, sickness, disability, frailty and one’s inability to contribute to the society would essentially diminish one’s dignity. All under the disguise of compassion.

Proclaiming death in the light of resurrection

Image by Wesley Tingey.

What then shall we do as God’s church to re-imagine, re-form and re-habituate our society’s perception of death and dying? How can the church ‘outnarrate’ – to borrow John Milbank’s termiii – the secular imagination of death and dying, which has ultimately deemed the sick, the disabled and the frail as being disposable and least valued?

Perhaps, the answer to that question is for the church to be more persistent and consistent in our proclamation of the death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

By persistently proclaiming the death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ, we effectively also proclaim that even God has suffered and does suffer with us and for us.

On the cross, God has actively and voluntarily taken upon Godself the most horrifying form of human pain and suffering – even to the point of death – so that our pain, suffering and death could inexorably become a glorious site of encounter with the Holy God.

In this sense, our pain and suffering have now become a meaningful invitation for us to be like God in Jesus Christ. No wonder St. Paul, in Philippians 3, expresses his longing to partake in Christ’s sufferings, “that I may know him, and the power of his resurrection, and the fellowship of his sufferings, becoming conformed unto his death; if by any means I may attain unto the resurrection from the dead.” For St. Paul, it is precisely in our participation to suffer and die with Christ on the cross, that we will also participate in His resurrection.

If then we are being shaped by the death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ, I believe this will shape our Christian imagination so that we regard the sick, the disabled and the frail as the most indispensable members of our society – hence greatly treasured and respected.

This is why in talking about Christians living as one resurrected body of Christ – with Christ as the head – St. Paul says in 1 Corinthians 12:

On the contrary, the members of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, and those members of the body that we think less honourable we clothe with greater honour, and our less respectable members are treated with greater respect; whereas our more respectable members do not need this.

But God has so arranged the body, giving the greater honour to the inferior member, that there may be no dissension within the body, but the members may have the same care for one another. If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honoured, all rejoice together with it.

Far from being the least valued or disposable, these treasured ones, in their human frailty, give witness to the grace of God who has suffered, died and rose again for the whole cosmos.

The death and resurrection of Jesus Christ proclaims that their suffering is neither forgotten nor ignored but is shared by Jesus – and to be shared by us – knowing that in Christ, who has become the first fruit of resurrection, we too will be resurrected and fully restored.

So, perhaps, as the church, after we have done challenging the deadly government’s legalization of euthanasia, we need to start asking ourselves consistently:

- Have we proclaimed the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in the way we do church?

- Have we proclaimed the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in the way we treat those who are sick, disabled and frail among us?

- Have we proclaimed the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in our church budget?

- Have we proclaimed the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in our every thought, word and deed?

i Read. Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007)

ii Raymond L. M. Lee, “Modernity, Death, and the Self: Disenchantment of Death and Symbols of Bereavement,” in Illness Crisis and Loss vol. 10(2), April 2002: 91.

iii John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory: Beyond Secular Reason (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990), 5, 6, 402.

Originally from Indonesia, Samuel Andri and his wife immigrated to Canada in December 2016. After graduating from Vancouver School of Theology (VST) in 2020, he is now serving as worship coordinator at the Dunwood Seniors Place Complex as well as youth pastor for Oakridge Christian Community, a ministry of Vancouver Chinese Presbyterian Church.

Well written Sam and you have affirmed many of my thoughts around MAID. Thanks for the article

Thank you Sam for shedding some light on this thought-provoking topic in another light.

This article is really thought-provoking, reminding me several times of family around the sick person who asked me to minister to their loved one who were being sick for years. I just consider it was MAiD, forthey were ready to release their loved one to the Lord. Thanks for this profound messages that related to the death and resurrection of Christ.

Sam, thanks for this. Thoughtful and well-written and hopeful. A demonstration of what it can mean to bear witness to the hope that we have. I’m gonna use that term ‘outnarrate’ for sure.

A lot to ponder. This is the first time that I’ve taken the time to read anything related to MAiD. Thank you for the post, Samuel.