Benjamin Perrin on The Social; he has been very active in the media on the issue of decriminalization of drugs.

Adults will be allowed to possess up to 2.5 grams of opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA in British Columbia by early next year.

That major shift in Canada’s drug policy was announced May 31 by Federal Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Carolyn Bennett, accompanied by BC Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson.

One of the most prominent voices making the case for that kind of change over the past few years is a professor at the Peter A. Allard School of Law at UBC.

Benjamin Perrin seems, at first glance, an unlikely champion of relaxed drug laws. A one-time lead legal counsel for Prime Minister Stephen Harper, he understands those who resist freer access to drugs – but he has been persistent in sharing the logic behind his change of perspective.

When Pierre Polievre, the leading contender for leadership of the Conservative Party, tweeted May 30:

Decriminalizing deadly drug use is the opposite of compassionate. Those struggling with addiction need treatment & recovery. Drug dealers need strong policing & tough sentences. . . .

. . . Perrin responded:

This is so disappointing. I used to think the same things, Pierre. Then I met with people in recovery and loved ones of people whose kids died of overdose. And I read the research. All of them said criminalizing people who use drugs made it worse. This isn’t a political issue.

Perrin has been clear that a major element in his change of mind is his experience of renewed faith. His brief profile on the law school site includes these words:

In recent years, Ben was confronted with childhood and intergenerational trauma, addiction, mental health challenges and disability in the lives of people close to him and his own. In this journey, he found freedom and peace in Jesus Christ. He is an advocate for compassionate, evidence-based approaches to pressing criminal justice and societal issues.

(In 2018 I wrote about a class I sat in on at the law school in which Perrin addressed the topic ‘Jesus & Justice: What would Jesus think about our criminal justice system and why should you care?’)

During an interview on CTV’s The Social March 5, he was asked what compelled him to write Overdose: Heartbreak and Hope in Canada’s Overdose Crisis.

During an interview on CTV’s The Social March 5, he was asked what compelled him to write Overdose: Heartbreak and Hope in Canada’s Overdose Crisis.

He responded:

Well, I was literally just driving to and from work, teaching criminal law here in Vancouver. It was around 2015 – 2016 and I just kept hearing story after story of people in the news who were overdosing and dying. Back then they were talking about individual cases.

I was going through a real awakening in my own faith journey, and I pulled the car over one day, literally, and I just said a quick prayer. I just asked God to give me a heart of compassion for people who are dying there.

I felt a real ethical obligation, and also a moral obligation. I’d been part of a government that had set up the contemporary approach to drugs that was clearly failing. Looking back from then to now, over that time-period, 25,000 Canadians have died during the opioid crisis.

He noted that the opioid epidemic has affected people across all socioeconomic and other barriers, but . . .

It has had a disproportionate impact on people who are disadvantaged and who have been really devalued by our society.

So when you look at who that impacts – people experiencing homelessness have been disproportionately affected, Indigenous people, significantly more likely to overdose and die, and people who have been recently released from prison. . . .

[In provinces like BC] more people have died of fatal drug overdoses in the last two years than died of COVID-19.

[In provinces like BC] more people have died of fatal drug overdoses in the last two years than died of COVID-19.

The Social co-host Melissa Grelo raised a point which many may have been muttering as they heard about the province’s new laws. She asked, “How do you close that gap for people who are like, no, if you’re using illegal drugs then that’s wrong and you should be charged with a crime . . .”

Perrin said:

Yeah, look, I was there – and that’s kind of why I wrote the book. As you started introducing me, I was Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s top criminal justice advisor, and now I’m the one here saying we need to decriminalize drugs, and provide a safe supply.

So, I’d say read the book. That’s the journey, that’s why I wrote it. I went and talked to judges, police prosecutors, investigators, people who use drugs, family members – that was the most impactful for me, was sitting in front of mothers whose children have died from the shame and the stigma of their addiction, because that’s what the criminalization of this does.

He encourages people to set aside their previous beliefs and “be open the the possibility that they need to be updated and changed.” He would like people to open their hearts:

It really speaks a lot to the society we live in that we’re blaming people, many of whom came to use drugs out of very deep pain and childhood trauma, and for me that was a real turning point – was to start to see people not as harmful names like addicts or junkies, but people who have deep pain that they’re often medicating, and they’re not at this part in their lives because they want to be there. Having that open heart is so crucial.

He recommended speaking to people with a new attitude:

I was surprised how, when I started talking to friends and family members, about this research and about how I’d changed my views, people started opening up. There were people I never knew who had issues with drugs who began to talk to me about that, because now I was a safe person.

Before, I was someone who they, rightly, assumed would be probably judging them or looking down on them. We need to sort of come to a place where we can understand and meet people where they’re at.

Perrin also recommended supporting Private Members Bill C-216 before Parliament which would decriminalize simple possession of drugs. That bill was voted on June 1 and did not pass.

Perrin’s website hosts several videos – interviews with The Social and BBC World News (June 1), but also a couple which would work well to initiate conversation in a home group setting:

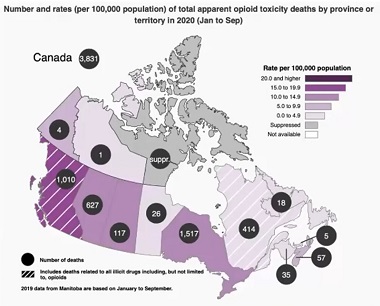

Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021.

He has posted a one-hour workshop for the Addiction Medicine Symposium 2022 at McMaster University’s Michael G. Degroote School of Medicine May 28. This one feature lots of facts, figures and graphs.

Another video is ‘A Christian Response to the Opioid Crisis,’ with Ambrose University, an evangelical institution in Calgary, March 4, 2021.

Perrin said:

As a follower of Jesus Christ, I see that we are really in a position where people are – as I did too – turning to all kinds of other things to deal with the pain, the trauma, the stress of our lives. As we turn to those things, we ultimately – it may take years, or decades – we find that they are bankrupt. They don’t ultimately work, and they all demand their cost.

People heal in community; that’s what the research shows. And the role of faith, actually, in overcoming addiction, is backed up by the research as well. There’s a real opportunity for people of faith to step into what is a tremendously painful and traumatic and complicated issue – and come with some humility and to come without a spirit of judgment and thinking that we’re better than others because we aren’t using those substances.

He carried on with what can only be described as his testimony and agreed with some who have described his about turn-about on the issue of drugs as a ‘road to Damascus experience: “That’s what, quite frankly, is supposed to happen when you meet Jesus.”

All things are legitimate [permissible — and we are free to do anything we please], but not all things are helpful (expedient, profitable and wholesome). All things are legitimate, but not all things are constructive [to character] and edifying [to spiritual life]. 1 Corinthians 10:23 AMPC

I totally want to approach this issue with an open heart and not stand in judgment of those who have made wrong choices maybe, but need help. My biggest concern with decriminalizing these drugs is that it would make it easier for kids to start that.

It is definitely a fact that since weed was made accessible to people over 18, lots more kids younger than that can be seen in neighborhoods smoking it – it has become available and we fear it will ruin their lives. That was not a helpful law! Will this law not also make those drugs more available and so ruin more people who don’t need the help of that law?

Thanks for this article.

Great question, Patricia. Decriminalization and legalization are two different things.

Alcohol and cannabis are legalized meaning anyone over 18 (or 19 depending on the province) can buy it freely.

I’m not recommending we legalize ‘hard drugs.’ Rather, that we no longer make it a crime for people to possess them (i.e. decriminalizing them). Criminalizing drugs contributes to shame, stigma, using alone, using faster and those increase risk of overdose deaths.

It also raises barriers to rehabilitation and gives people criminal records that can prevent them from getting some types of employment or housing. So decriminalizing drugs doesn’t make them more widely available to people, it just treats people who are addicted them more humanely.