I’ve just finished reading four books on anorexia nervosa. This sudden interest in Eating Disorders (referred to hereafter as ‘Ed’) is not, as you might have guessed, coming from a random, casual interest in the subject.

I’ve just finished reading four books on anorexia nervosa. This sudden interest in Eating Disorders (referred to hereafter as ‘Ed’) is not, as you might have guessed, coming from a random, casual interest in the subject.

This dreadful disease has completely upended our lives. Ed took over the mind of one of my children somewhere around May or June of this year.

He breathes subtle lies about the importance of being skinny and how bad fat is. Come on, don’t you want to be healthy? He whispers. He picks on conscientious young girls who are hard-working, disciplined and diligent. He takes these virtues, and, with destructive malice, he redirects them towards a deadly goal – self-starvation.

Ed is like that loser boyfriend who uses guilt, shame and blame to control and manipulate his poor unsuspecting girlfriend. He uses all the dirty tricks until he has total domineering control over his victim. Ed doesn’t let go until he has destroyed the person. If ever there was a bad boyfriend who needed to be scared off by a dad’s shotgun, this is he. If only it were that easy.

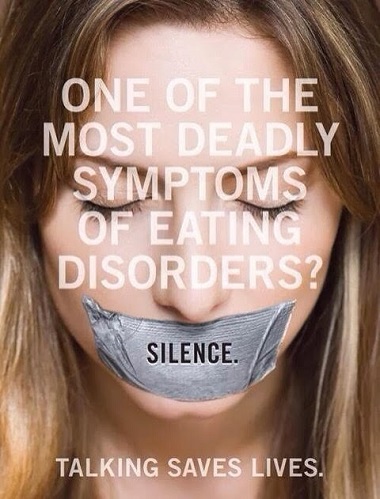

Ed is a parasite, a monster, a demon and a terrorist. This disease is so maddening because the one who has it is unable to comprehend the severity of their predicament, and no amount of rational conversation can alter that. Once Ed has control, there is no chance of ‘talking some sense into’ the sufferer.

With cancer or diabetes, you naturally want to get better and are willing to do whatever it takes to make that happen. But not with Ed. There is only one cure for Ed, one medicine which will make him go away – food. And food is the one thing Ed will not allow.

We didn’t know Ed was whispering in our daughter’s ear. All we saw was a happy, successful kid enjoying life. She was always a bit more health conscious than her siblings, but we didn’t fault her for that. So what if she wasn’t mowing through junk food like the others; it was probably a good thing.

School finishes on a high note. Our daughter receives straight A’s, and her hockey team wins the championship. She and I make plans for power skating school in the summer and to climb Garibaldi together. But first, there are two weeks of summer camp. This is an excellent opportunity for her to be a junior counsellor, so off she goes.

When she comes back two weeks later, I hardly recognize her. Her eyes are sunken in, her body reduced to skin and bones. “Honey, what is going on?” I question with mounting concern, “You look like a holocaust victim!”

Ed is ready for me with a hundred excuses designed to convince me that self-starvation is somehow a good thing – most of them centring around healthy living. Mistin and I are not convinced. We ring up our doctor and schedule an appointment.

During the intervening week, our daughter’s attitude and behaviour around food becomes increasingly bizarre. She converts to strict vegetarianism. Bread is now bad. Any kind of sauce is out of bounds. Butter becomes a disgusting menace to be avoided at all costs. She takes over meal planning and cooking. She constantly reads up on nutrition and all things relating to food. One evening, she bakes banana peals for us! She pushes food around her plate but eats very little of it.

When we encourage her to eat, she says, “no, thank you” if we insist, she acts terrified or angry. She’s so confident in her decisions. Finally, we stick her on the scale, and the puny number that registers back up at us, makes our mouths fall open. “What the heck is going on with you?” Again more excuses.

We share all our concerns with the doctor. He gives a good speech about the need for a balanced diet and the consequences of not correctly fuelling the body. He is concerned because our daughter has also been missing her period, so he schedules an appointment in three weeks with a pediatrician. Since we are going on vacation to Malaysia in a few days, we use his counsel to map out a food plan to keep us on track while on holiday.

The moment we board the plane for Malaysia, the food plan goes out the window. Our sweet, kind, compassionate daughter becomes belligerent, angry and vindictive whenever we encourage her to eat. Her personality change is so shockingly dramatic that we sometimes can’t even recognize her. We shake our heads in despair and ask, “Who is this person, and what did they do to our daughter?” “Come back to us,” we say to her, but she’s gone.

By the second week of our holiday, we are all petrified. Like a flashlight running out of batteries, she is shutting down in front of us. She experiences cognitive delays, and her motor skills slow right down. Her body starts acting up. She blacks out a couple of times, has a panic attack, she develops fine white hair all over her body, her feet and ankles swell, and she gets a nasty rash. She smells bad. I’ve since learned that that smell comes from the body cannibalizing itself in a desperate attempt to survive.

In addition to self-starvation, Ed has another morbidly sadistic point of attack. Not only must my daughter not eat, but she must also exercise relentlessly. He screams in her ear that she is a fat lazy, worthless pig if she is not constantly in motion. So while the rest of us are sitting down to enjoy Malaysian cuisine, our tortured child is off in a corner cranking out jumping jacks.

Mistin and I go into panic mode. We scream at our daughter to eat, we threaten her. We preach sermons to her. “Jesus wants you to eat. He wants you to enjoy your food; that’s why he gave you tastebuds!” We guilt trip her. We try coaxing, bribes, humour – anything we can think of to break this demon-like spell she is under. But no luck.

Her siblings are all going crazy now too. Everyone can see that she is in mortal danger. Everyone but her; Ed has blinded her. She stares blankly at us all, unmoved by our skyrocketing concerns. She admits she’s a little tired, but on the whole, she is convinced that her lifestyle choices around food and exercise are for her good. Ed smiles; he’ll have another one in the grave before long.

We arrive home on a Saturday utterly shaken. Our Tuesday pediatrician appointment can’t come soon enough. On Sunday morning, our afflicted daughter forces herself out of bed and announces to the jet-lagged family that she will be going on a 10 k run. We talk her down to a 5 k and demand that she eat something before she heads out with mom. A fight ensues when a measly carrot stick is forced upon her. In anger, she flies out of the house.

At the end of the run, she loses consciousness and smashes her face on the concrete. We are beside ourselves with worry and fear. The ambulance comes, and we spend the next eight hours in the ER. I tell the doctor that our daughter needs to be admitted to the hospital. Whatever is going on is beyond our ability to fix. They talk it over but finally decide to release us. It’s a call for the pediatrician to make. They say that Tuesday will be here soon enough.

“Soon enough” does little to soothe us. We lock our daughter in the house and watch her like a hawk. She’s offended. She won’t eat and tries to do push-ups and sit-ups when we are not looking. The stitches in her face do nothing to give her pause. On Tuesday, the doctor runs some tests. He discovers that our daughter is on the verge of heart failure and brain seizure. He orders us immediately back to the hospital.

For the next eight days, Mistin, I and our daughter are in lockdown at the hospital. Mistin takes the day shifts; I take the night shifts. Re-feeding is a no-nonsense jail-like situation. Six meals a day, complete bed rest and constant monitoring. Any funny business, and you get a feeding tube shoved down your nose. Our daughter complies. The diagnosis comes in: anorexia nervosa.

The hospital stay is already six weeks in the rearview mirror at the writing of this blog, and we’ve yet to see any improvement in our daughter other than weight gain. Ed still holds complete sway over her. But thanks to what I’ve read, a support group and a compassionate therapist and pediatrician, we are clinging to the hope that at some point after our daughter establishes a healthy weight, the voices in her head will diminish to such a degree that she can have a healthy relationship with food again.

Ed has cost much for my sweet daughter. No school, no mountain climbing trip, no hockey season, not even any exercise to speak of. The re-feeding continues at home, just like in the hospital. There is no chance she will get better if she doesn’t get to a healthy weight.

Since Ed has scrambled her brains around eating, we’ve had to radically alter our schedules to ensure we are present for a half dozen feedings a day, each one taking over an hour to complete and usually full of screaming, crying, rage and all manner of vocalized despondency.

This is easily the hardest thing Mistin and I have ever had to do, but we will not give up. We love our daughter too much to let Ed win.

Things I’ve learned along the way:

- Parents are of vital importance in overcoming Ed: This wasn’t always the case. Prior to the mid-1980s, the assumption was that bad parenting and dysfunctional families were the underlying reason for the onset of eating disorders. A ‘parentectomy’ was the order of the day by professionals. However, this is no longer the case. Research in the last 30 years has shown that Family Based Therapy (FBT) has a much higher success rate than traditional methods that restrict parental involvement.

- Don’t worry about the why; focus on the what: We always want to figure out why something happens, but in this case, it’s a wasted effort. It’s a rabbit hole with no clear answer or helps to offer. What we have in front of us is self-starvation, and it needs to be treated through re-feeding. So our energies focus on this.

- Early warning signs: There is no reason for a healthy child or adolescent to restrict his or her diet. Restriction is always the first sign of Ed. ‘No restriction only moderation”’ is the best motto to have. For girls, life-threatening starvation is evident when the menstrual cycle ceases.

- An intervention is necessary: The adolescent who suffers from anorexia has experienced severe brain trauma. In many cases, their brain has shrunk. It is foolish to assume that someone in this state of deterioration would be able to make good choices about food. With Family Based Therapy, the parents are empowered to take complete control over the eating and exercising options of the child.

- Anorexia is a killer: Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. Most of the victims succumb to heart failure.

- Victory requires a war of attrition: Ed will fight against FBT. But compassionate firmness with your child is the only proper course. We don’t negotiate with terrorists, and Ed is a terrorist! “She eventually realized that we would never back down on our expectations and that we would not allow any meal not to be eaten. Yes, we were exhausted but our determination and repetition paid off, and eventually, she realized it was less tiring for her to eat than to fight against us” (P. 60 Survive FBT)

- Unity or all is lost: The parents must be on the same page, same line, same sentence and the same word or Ed will exploit the variance and slip through the cracks.

Brave Girl Eating: The heart-wrenching true story of what it’s like to go through this nightmare. It’s a scary book with troubling statistics and not necessarily a happy ending, but it gives you the up close and personal with this rotten disease and a lot of the historical backdrop behind it.

Survive FBT: Simple, straightforward and short in length. This book gives you a fist full of tips and tricks to smash Ed in the mouth and restore your child to a healthy relationship with food.

Helping Your Teen Beat an Eating Disorder: This is the flagship book for FBT. It’s research-oriented yet full of stories. This book is given over to the idea that parents are part of the solution, not part of the problem.It covers the entire spectrum of eating disorders, not just anorexia.

Talking to Eating Disorders: The least compelling of the four books. It supports a philosophy of gentle support, not direct intervention. All I know is that if I had listened to this book, my daughter would be dead by now.

This comment is re-posted by permission from Dennis Wilkinson’s blog, In ‘Search of Better Stories.’ Following 10 years of church planting in the West End, he is now the building administrator of the Veterans Memorial Manor in the Downtown Eastside.

Thank you for sharing this Dennis. My heart aches for you, Mistin, your family and your daughter and all those dealing with this horrific disease. Prayers. . . .