The Fellowship of the Ring journeyed to Mount Doom in order to destroy the One Ring.

I’ve come to believe fantasy literature is a vital source for spiritual formation. But this belief hasn’t come naturally.

I’ve always been a realist, even as a kid, perhaps a hangover from my Depression-era ancestry. My reading list, when I was a young Christian, showcased books outlining the basics of faith and Christian practice, expository texts, laying out propositions and explanations as rational as rows in a cornfield neatly fenced in.

They were fine books, but after reading a few, they started to sound the same. I wanted something more than cornfields.

It wasn’t until my college days that I broke the covers of C.S. Lewis, Tolkien and Charles Williams, immersing myself in their fantasy literature. The imaginative journeys through other worlds grabbed me like no theological text could. These writers quickly became shapers of my Christian journey. The images, characters and stories have stayed with me.

So, why were the works of these giants seldom highlighted as a source for Christian spiritual formation in my church library, not as stories just for kids but essential for all?

When I reflect on my first halting steps of faith as a boy, I remember it was the stories that hooked me, stories throughout the Bible but especially in the gospels. The gospels, I noticed, even had stories within stories – Jesus’ parables.

I liked the fact that Jesus seldom explained them, that he didn’t feel the need to write a book detailing what his parables were meant to convey. He gave his audience space to wrestle with his stories, savour them, sleep on them and turn them over in their imaginations so that in due course the stories could work their way like seeds into the soil of the soul.

Jesus obviously thought his little parables were big enough to communicate good theology. His stories penetrate, living and breathing with the fodder of everyday life.

In the image of God, we also tell stories – true ones, fiction, fantasies even – because they are grist for human growth and the health of the community.

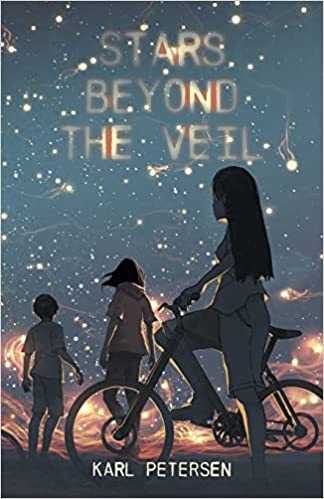

When I first told stories to my children, they would insist I tell my own rather than ones from a book. At one point, with fear and trembling I set out to write a fantasy novel for young readers, something I probably would have never attempted but for my kids. The book received some modest praise.

When I first told stories to my children, they would insist I tell my own rather than ones from a book. At one point, with fear and trembling I set out to write a fantasy novel for young readers, something I probably would have never attempted but for my kids. The book received some modest praise.

Then I wrote another and noticed adults were reading the novels as much as kids were. I suppose, why not? Didn’t Jesus say we should be like children, as imaginative and as tender-hearted as they are, if we expected to fathom the mysteries of the kingdom?

Eventually, it dawned on me that I should try using my fantasy novels with my university students as reading texts. Their responses should not have surprised me, but they did.

They were not only drawn in by the stories, but the stories engaged them in critical thinking. They wrestled with the novels’ themes in a way they hadn’t engaged with expository texts. Some had questions about the fantasies’ spiritual insights. Others felt a resonance with their own social contexts.

Why did these fantasies seem to reach them in this way?

Fantasy, perhaps even more so than realistic fiction, has the capacity to address the major questions of life that all religions strive to address, through themes of good and evil, personal character, social responsibility, love and justice, societal breakdown and restoring order, political authority and divine authority. In fantasy, we find broad story arcs that hold significance for not only one character but entire worlds. The themes are religious in nature.

Fantasies have one other way they take readers on the quest for religious significance – symbolism. In fantasies, symbols play a major role in shaping a story’s meaning. The permanent winter in Narnia, for example, represents the moral decay of the land under evil rule. Tolkien’s ring represents the enslaving urge for power for anyone who possesses it. And when Frodo drops the ring into the crater of Mount Doom, not only does he vanquish the ring’s power over himself, and over the Shire, but over the world.

These symbols are spiritual and universal in their significance. Churches would do well to include good fantasies as required reading.

The beauty of good fantasy literature is that the spirituality of the work sneaks up on us often unawares and gets under our skin only to surprise us later. We may find ourselves longing for something beyond normal vision. Fantasy is unique this way in that it paints with bold strokes realities that normally go unseen, evoking a desire that is essentially spiritual.

Karl Petersen

Lewis describes this desire as a longing for “a country we have never yet visited” (The Weight of Glory), a country the human heart nevertheless senses is real, perhaps more real than the one we have known.

Karl Petersen received an MTS from Regent College and an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC. He has published two collections of poetry, a childhood memoir and two fantasy novels for young adults – The Kingdom of What is (2017) and Stars Beyond the Veil (2022). He teaches English at Kwantlen Polytechnic University and lives in Vancouver with his wife and two girls.

Hi Karl,

Your writings resonate in my heart. In this writing, I especially liked your reference to the parables that Jesus told. “Jesus obviously thought his little parables were big enough to communicate good theology. His stories penetrate, living and breathing with the fodder of everyday life.”

I have come to love Jesus more and more as I watch him teach and interact with the people while watching the series The Chosen. Keep on writing, brother! Much love from us.

Hello great Teacher Karl,

I read your two books; the level of your imagination is incredible, inspiring and unique. I can’t wait to retire in Africa and take your books in my village.

In this article, I love the example of the the parables of Jesus, you reminded me of the parable of the good Samaritan, where he meant ‘we must love one another.’ We the people and the church have a long way to go.

Thank you for your teaching