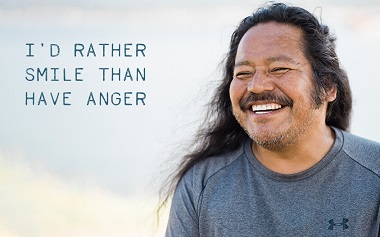

Frank was raised in a small Nisga’a village before moving to Vancouver at age 12. Photo: Solomon Hsu

Four years ago, I was laying on the street in the Downtown Eastside, about to try heroin for the first time. But then, I turned over and saw the UGM sign. If it weren’t for that, I believe I’d be dead today.

Frank grew up immersed in the traumatic effects of the Indian residential school system

I’m from the small Nisga’a Village of Gingolx. When my parents were sober, they were the best ever. We always had food in the cupboard. My dad would take me out crab fishing. We’d bring firewood and make a day out of it. It was awesome – I remember so many great things.

But things would get scary when the parties happened. I lived through alcoholism and violence. I saw my mom getting beaten up. Rape, violence, abuse. Guns being shot off, people almost being killed, cops taking away my dad.

When I was young, I didn’t know about the residential schools and the effects it had on my dad, mom and Native brothers and sisters.

But later, my dad told me what happened to him. That when he’d speak his language at school, the nuns would grab a metal brush and make him scrub the brown off his skin. And when he’d speak up, they’d lock him in a cellar and starve him for weeks.

I used to always wonder why my dad was angry and abusive. I used to be mad at him for that. But now that I know why, I’m not. It’s really just heartbreaking.

Frank’s family moved two hours south to escape the ongoing violence when he was 12

Moving from a reserve to a big city was totally different. That’s when I first started dealing with racism.

Groups of white people would see me walking down the street and start running after me. They’d say, “Let’s go kill that Indian!” I’d have to run for my life. I was just a kid.

As I grew up, I used soccer as an outlet to deal with the racism and hurt inside of me. I would always wonder why I felt mad, but I used that to train really hard.

Soccer helped Frank cope, but when tragedy struck again as an adult, he turned to alcohol

One day, the cops came to my house and said, “We busted your former elementary teacher in Gingolx for drugging and sexually abusing you and your childhood friends. He’s in custody in Vancouver.” I couldn’t believe it.

Two weeks later, the cops came and told me, “Your dad died in police custody.” My older brother called and told me too. I instantaneously started crying, and left my job as a youth worker.

I tried continuing with soccer, but I started partying so much I was unable to train and recover properly. My body was too pickled up on booze and I always was hungover to hell.

Legal justice was eventually served for the teacher’s abuse, but that didn’t heal Frank’s deep anger

By then, I had moved to Vancouver because I wanted to look for the teacher who raped me, and the police who killed my dad – I wanted to kill them.

But when I got here, I was introduced to crack. I got numb from it and forgot what I came here to do. It was a curse, but a blessing at the same time. It stopped me from becoming a murderer.

I won the case against my teacher, but I saw it as blood money and I didn’t want nothing to do with it. So I used it all in one month on drugs.

Frank spent several years hooked on alcohol and drugs, often homeless. Photo: Solomon Hsu

Frank continued spiralling into addiction over the next decade

I was still working and getting paid, but I was spending all my money on cocaine and using more and more.

I also became homeless on-and-off for 10 years, after my mom passed away. Sometimes I’d sleep in alleys or on soccer fields. But I always tried to make it to emergency shelters – I even slept at UGM a few times.

That all ended up with me neglecting my son. I’ve cried a lot about not being there for him. . . . it’s something I feel a lot of shame about, since I was yearning to have my own father figure back.

But over the years, I met people who also didn’t want to deal with things. They used drugs to numb themselves. So I learned to not care and numb myself too.

Frank was living at rock bottom and eventually reached a crossroads

I remember laying across the street thinking, “This crack’s not doing anything for me anymore. Should I try heroin needles now?”

I walked in and said to Mike, an outreach worker, “I’m as high as a kite. If you don’t have a bed for me now, I’m not coming back.” He brought me in right away. That was amazing – I still thank him for that to this day.

I look back and know it was a miracle I saw the UGM sign. If I didn’t, I believe I would be dead today, because that’s when fentanyl got into everything, and the opioid overdose crisis started.

In recovery, Frank confronted his trauma and embraced forgiveness, leading to deep healing

At first, I didn’t know what to think about being at UGM and being Native – knowing what Christianity and residential schools did to my people. But the chaplain and counsellors really listened to me and apologized. That’s what made me stay – I could see that the people at UGM actually care.

In one of the teachings, I learned that Jesus says not just to forgive someone once. You forgive them 777 times. That was eye-opening: learning to forgive others, and forgive myself.

People now ask me, “Why do you smile so much?” I tell them, “It’s because I forgave the police. My abusive teacher. All the racists. I forgave myself, for hating my Native identity and hurting my family. Now, I’m proud of who I am.” I really believe in the power of forgiveness.

Since recovery, Frank has continued rebuilding his life through education, which has brought both pride and peace

I went to Native Education College to finish English 12, a graduation requirement I was short of for 29 years. Being around other Native students really helped me. And the Elders and teachers were always there with encouragement when I felt hopeless. Since losing my parents, I’ve been looking for that kind of wisdom and guidance again.

When I was almost finished, my teachers came up to me and said, “Frank, we’re so proud of you. We know your story. Your grades are great – you’re on the Dean’s List! We want you to be one of the valedictorians.” I couldn’t believe it!

Then I got into SFU’s Aboriginal University Preparation Program. I’m the first person in my family to ever attend university, so it’s a big feat! In the first few months, I was crying on the bus all the time. I couldn’t believe I was actually going to university!

Today, you can find Frank with a smile on his face, and optimism that extends beyond himself

Frank is now attending Simon Fraser University. Photo Solomon Hsu

When I first came to UGM, I wanted to show my family I can be a better person. I couldn’t live that way anymore – drunk, addicted and homeless with nowhere to go. So I took a chance on straightening up my life.

Now, I have a strong sense of purpose. I’m four years sober and in the third year of my Environmental Science degree.

I’m surrounded by like-minded people with similar goals. I never had that before – people would just tell me, “You’ll never amount to nothing, except for being a drunk like the rest of your family.” But today I have people in my life standing beside me as I better myself as a human being.

Through my education and recovery, I’m hoping to show my family, Native brothers and sisters, and everyone else that if I can do it, they can too.

This reflection is re-posted by permission.

UGM’s mission: “Demonstrating the love of Christ, Union Gospel Mission is determined to transform communities by overcoming poverty, homelessness and addiction, one life at a time.”

Powerful!

Frank’s testimony is so beautiful… Overcoming stories such as this one shows that God always cares IF you follow his lead… Frank knew UGM could provide and move him through… WOW!!!! Such a blessing!!!!!