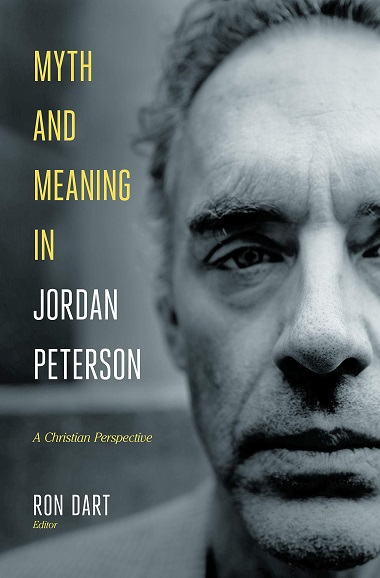

Jordan Peterson often draws on the Bible and religious themes in his writing, so Ron Dart’s brand new book – Myth and Meaning in Jordan Peterson: A Christian Perspective – is timely. He has edited 10 essays which assess Peterson’s thought.

Jordan Peterson often draws on the Bible and religious themes in his writing, so Ron Dart’s brand new book – Myth and Meaning in Jordan Peterson: A Christian Perspective – is timely. He has edited 10 essays which assess Peterson’s thought.

Dart, who teaches in the Department of Political Science, Philosophy and Religious Studies at the University of the Fraser Valley in Abbotsford, was interviewed by Mark Bauerlein for a First Things Podcast that was posted May 11.

Following are three excerpts.

Mark Bauerlein: The quote on page 3 really gives us a rationale for the book: “This book is an attempt to understand, from a Christian perspective, what has caused so many people to resonate with Peterson.”

I mean, Peterson is this international phenomenon that hit a few years ago, but the book implies that somehow, how Christianity is addressed by Peterson, or comes through Peterson, is an important part of his appeal. Is that correct?

Ron Dart: Yes, I think very much. . . . A lot of [Peterson’s] lectures, his thinking, going back decades – he’s sort of like a Virgil, pointing towards the ultimate, towards Christianity. He himself has not taken that step, but a lot of the myths and the archetypes, his exegesis of the Bible, Old Testament, New Testament, is very much leaning in that particular direction.

Many, many Christians – some who have come out of a fairly Reformed background, with a more literal, grammatical approach to the Bible, have been very much taken by Peterson’s much more sophisticated and nuanced exegesis, that you will find certainly in the Roman Catholic tradition, with its four-fold notion of exegesis.

His attempt [is to say that it is not enough] merely to understand Christianity through a creedal, confessional background, without it having any meaningful existential relationship to how we live, how we understand ourselves, the dark or the shadow side, how we have to face into that – like Dante going down into the Inferno, the journey downward, the journey upward – he works on all these great classical myths found within, at their best, the Christian tradition, but also found in other religious / philosophical traditions.

So there’s something very intellectual about what he’s doing, but also very, very experiential as well, that speaks to people who probably want to go deeper in their faith of self-understanding and then apply that practically in their lifestyle as well. . . .

MB: One of the opening essays in the book is by Bruce Ashford, which says that one of the primary advances in Peterson’s work has been “to unmask secular modernity.” What is it about secular modernity that Peterson’s work and lectures have unmasked?

RD: Modernity or secularism can go in a variety of directions, but one more ideological path it’s taken is either a negation of spirituality and religion or a subordinating of spirituality and religion. For those who come from a commitment to a religious background of one form or another, the notion that somehow it has to be banished or marginalized or subordinated, and the ideology of a harder, aggressive secularism sits on the throne – Peterson comes along and basically says the emperor has no clothes on.here, and this is very much a cyclops way of seeing the sort of one dimensional secularism.

His openness to the great myths of Christianity and other religions, and what that means in terms of one’s spiritual journey and adventure and pilgrimage through time – he deconstructs a certain form of secular modernity, and says it blinds people to a much greater reality of which world civilizations of the past, and today, still see as essential to what it means to be human and live a meaningful and authentic life. . . .

MB: When Peterson resisted this law in Ontario about pronouns – that really prescribed how you will use pronouns – that’s when he got his back up and he simply would not bend. The University of Toronto, his institution, sent him a couple of letters saying, look, you better knock this off because you’re violating the law and you’re also violating University of Toronto regulations.

Why didn’t Peterson just lighten up and go with the flow and relax? Why didn’t he just go quiet? What was it about him that said no?

RD: Probably there’s two things at work. There’s a tendency of academics to sit around the campfire, talk to one another, publish articles, publish books, do the conference circuit, almost in a monastic way – stay quite distanced from the more intense public culture wars.

Peterson, like an earlier C.S. Lewis, for example, who could have stayed at Oxford – he’d done his earlier Allegory of Love – and the notion that he would write more popular books or go on the BBC, this was a demeaning of the academic profession, becoming populist.

Peterson could have stayed in the Department of Psychology at U of T, he could have continued all his articles, done the conference round and become the junkie in terms of one more article, one more book.

But he thought something more important was at work – and that’s what Milton said: “I cannot praise a cloistered virtue that never sallies forth.” There can be a cloistered virtue at universities, even though they’re pulled obviously in different ways ideologically. But they don’t sally forth into very demanding and controversial issues, where you know you’re going to be fired at in the public domain.

For Peterson, this notion of truth, and particularly the importance of the individual in true speech, or the sovereignty of the individual being true to what they know is important against a herd mentality. And this is the danger of a certain type of ideology; it can become very herd-like. This is social justice warriors.

He sees it at obviously a more enlarged area – former communism, this is why his interest in Solzhenitsyn, fascism, Nazism. And he sees it being played out – obviously in not as gruesome a way as that – but within elements of the progressive left, as well as in the alt-right, the light-right.

He maintains the centrality of critical thinking – and this is where his doubting side comes in as well – grappling with the truth as much as he can understand it in any given time, against a herd mentality that essentially hunkers down, hoofs in the ground, and says we know what it’s all about.

He maintains the centrality of critical thinking – and this is where his doubting side comes in as well – grappling with the truth as much as he can understand it in any given time, against a herd mentality that essentially hunkers down, hoofs in the ground, and says we know what it’s all about.

The content of that can be very damning to not only the human soul, but the people who have stopped thinking critically about truthful issues. . . .

Go here for the full 31-minute interview.

Ron Dart has authored or co-authored 35 books that deal with the interface between literature, spirituality and politics, including The North American High Tory Tradition (American Anglican Press, 2016) and Christianity and Pluralism (Lexham Press, 2019)