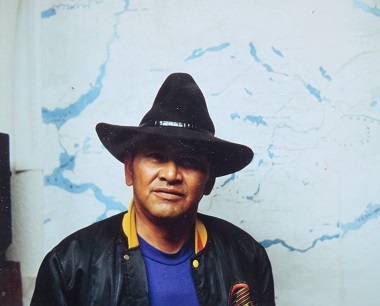

Chief Marvin Charlie told us how he lost his home.

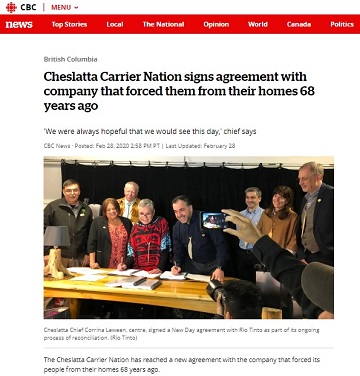

‘Cheslatta Carrier Nation signs agreement with company that forced them from their homes 68 years ago.’ That CBC News headline took me back to a momentous (for us) family trip to three reserves back in 1993.

Reflecting on the trip reminds me of several things – how naive (almost ignorant) we were about the lives of Indigenous people in our province; how bad things were for them due to colonial practices; and how slowly things change. But I do see some signs of change in terms of settler/Indigenous relations – among the Cheslatta, for example, but also for our family (and for many others in the broader culture).

Cheslatta

I remember meeting with the leader of the Cheslatta people in a modest band council building while our kids were outside, watching as his teenage son returned from a successful hunt with a deer loaded onto the back of his pickup truck.

Here is what I wrote about that meeting for the September 1993 issue of Christian Info News (later BC Christian News), as a sidebar to a larger story about the whole trip:

Chief Marvin Charlie of the Cheslatta Nation (south of Burns Lake) told us how, as a boy of eight, he and the whole band were forced to leave their traditional home when Alcan flooded the whole area as part of the Kemano hydro-electric project in 1952.

The Cheslatta people heard April 3 that they would have to move. Flooding began April 21. Some band members who were out on the traplines came back to a settlement which had first been burned, then flooded.

The Cheslatta people went from being self-sufficient to being heavily reliant on government programs. Charlie and many others have had problems with alcohol before starting to collect themselves. The band members are now rehabilitating themselves and some of the land near their old home.

Now Alcan is pursuing a second phase, called the Kemano Completion Project, which, with Kemano I, will result in at least an 80 percent reduction of flow in the Nechako River. And it would wipe out the value of work the Cheslatta people have done so far.

Now Alcan is pursuing a second phase, called the Kemano Completion Project, which, with Kemano I, will result in at least an 80 percent reduction of flow in the Nechako River. And it would wipe out the value of work the Cheslatta people have done so far.

The Kemano Completion Project was cancelled in 1997, though Alcan been given permission to proceed a decade earlier and had invested $1.3 billion in the project.

The CBC News story reported that things are looking up for the Cheslatta people, but only after long years of struggle. They said:

Go here for the full story.

Dog Creek

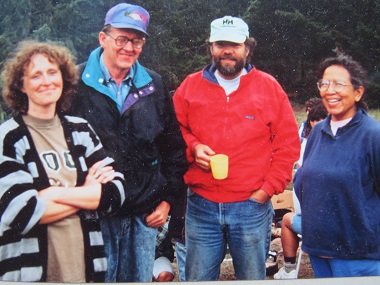

My wife Margaret (left), with Darryl Klassen beside Chief Agnes Snow.

Our family’s stop in Cheslatta was just one part of a guided visit to meet members of the Shuswap, Carrier (Cheslatta) and Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en nations. Darryl Klassen of the Mennonite Central Committee introduced us to many people with whom he had built up relationships over several years.

I introduced the article I wrote in this way:

We were a little apprehensive. We knew something of Native issues, little of individual Native people. Our five children were clearly looking forward more to Barkerville and lake swimming than to meeting Indians.

Our 10 year old boy was interested – to our chagrin – in “cowboys and Indians.” Our eight year old daughter wondered if we would have to learn another language to talk to them. But we were on our way.

We began by joining people from Dog Creek and Canoe Creek (Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation) at their high plateau summer camp:

Before long, our kids were telling us how much they like the people, how the kids were nicer than kids in the city (read, less aggressive). They loved the baseball games. Some of them liked the food.

For most of us, a feast involving great numbers of salmon and deer ribs cooked over an open fire was a highlight.

But the real high points were the times when we had a chance to talk with people. One morning, Chief Agnes Snow and a good number of others sat down with us to talk about their lives.

The Catholic-run residential schools are still with them, even though they no longer operate. Most in their thirties and older had gone. They told us about living away from home most of the year; about the identification numbers they went by; about the regimentation; about feeling lonely all the time, separated even from siblings. . . .

Chief Snow was reflective: “We must be a strong people to have come through what we have come through . . . and then begin to heal.”

K’san

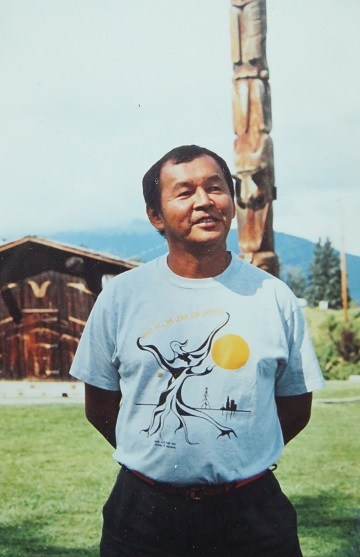

Wii Seeks, defender of Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en territories.

I wrote this about a unique man we met in K’san:

Wii Seeks is a veteran of many roadblocks and other attempts to extend the effective control of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en people in their traditional territories north and south of Hazelton.

He pointed out that his people have been less touched by white culture than groups further south. They are not hesitant to assert themselves.

He told us a tale of taking a group of native people from BC’s northwest to protest the quincentenary (1492 – 1992) of Columbus’ discovery of America in the Caribbean. They went a step further than he had expected by taking over a replica of the Santa Maria.

Wii Seeks said he would be happy to see BC divided up among the native nations, but added with a mischievous grin that ‘we have to aim high so we get something.”

The Gitxsan keep a History of Resistance on their website, beginning in 1830. One entry reads: “1988 (February 29) – Chiefs place huge cedar tree across Kispiox Valley logging road. Wii Seeks, Ralph Mitchell, and Wii Muugalsxw, Art Wilson lead the blockade.”

Three conclusions

1. A lasting influence

When I mentioned what I was writing about to one of my sons, he said that as a boy he had been particularly impacted by the stories of dispossession that he heard on our trip. Today he is an archaeologist who works with a Coast Salish community in the Fraser Valley and is half way through his PhD, the theme of which, roughly, is ‘the archaeology of Aboriginal rights and titles.’

The ’10 year old’ is also an archaeologist, also working mainly with Indigenous communities. Both girls have worked with First Nations people, one through her anthropological training and the other with a local church after-school program.

2. Thank you Mennonites

Our family remains very thankful to Darryl Klassen and to the Mennonite community that supported him as he made friends with Indigenous communities around the province – and then introduced us, and others, to them.

Steve Heinrichs is continuing with that work, albeit in a different way; I wrote about him a couple of weeks ago.

3. Reconciliation takes time

The progress towards reconciliation is slower than it should be. But there is some forward movement, as we have learned in our family. I was brought up, in Vancouver, with minimal knowledge or concern about Indigenous people. Our children are more alert and involved than we were.

The fact that the Wet’suwet’en issues are so high profile in Canada right now shows that Indigenous land claims will not fade away, and increasing numbers in the general public understand the intrinsic merit of those claims.

Very interesting comments. We need more info from behind the headlines about these issues.

Ever thought about writing a book, Flyn?

Thanks Pat. I’ll think about it – but for the moment I’m too busy collecting and reading some of the amazing books already written.