Alan Twigg, publisher of BC BookWorld and BCBookLook, wants to help out Father Placid and the community of Luhombero in Tanzania.

Alan Twigg is probably best known as publisher of the ubiquitous BC BookWorld, but he also runs BCBookLook, (“dedicated to continuously promoting the literary culture of British Columbia”) and ABCBookWorld (“the Wikipedia of BC Literature”).

Though Twigg notes that he has no affiliation to the Roman Catholic Church (nor, I believe, to any church), he has of late taken it upon himself to help out Father Placid Kindata and Luhombero, “the poorest and most remote parish in the Mahenge Diocese of western Tanzania.”

Following is his March 1 BCBookLook article, re-posted by permission.

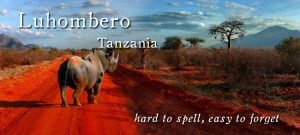

“I didn’t go to Tanzania to see hippos and zebras. I went there to learn about a pioneer in the treatment of epilepsy, Dr. Louise Jilek-Aall. And instead I discovered Luhombero, a place that’s hard to spell and easy to forget.

How I found Luhombero

In 1960, while working alone in Tanganyika in her twenties, Dr. Louise Jilek-Aall responded to an emergency Red Cross request to manage a large hospital in the Belgian Congo (now Zaire) during the worst of the bloody civil war. She was taken to Matadi on the Congo River in a United Nations helicopter. All the Belgian doctors had fled. Conditions were horrendous. She had a Swiss degree in tropical medicine. She stayed.

In 1961, she visited the Nobel Peace Prize-winner Dr. Albert Schweitzer at his riverside clinic in Gabon. Impressed by Jilek-Aall’s experience and intellect, he asked her to remain on his staff. She stayed. Later she wrote a book about their time together.

Even since then the Norwegian-born Dr. Jilek-Aall has been making medical history by managing an unprecedented program for rural epileptics in eastern Tanzania that she started in the early 1960s. The inland clinic in Mahenge attracts patients from all over the Ulanga District where the prevalence of epilepsy is 10 times higher than the global norm.

Male colleagues all said it would be impossible to get African patients to take their medications regularly. Thousands of recovering epileptics later, having become a psychiatrist and anthropologist along the way, the beloved, multilingual “Mama Doctor” is no longer able to travel to Africa from her home in Tsawwassen.

That’s where I came in. Somebody had to write a biography about this person.

Travelling to Tanzania, I took a small, crowded ferry across the Morogoro River and didn’t see another white face for two weeks.

Father Placid

In the process of visiting Dr. Jilek-Aall’s still-functioning clinic – basically a refurbished shack on the grounds of a little hospital at Mahenge – I met one priest who clearly stood out from all the rest.

The affable and ever-capable Father Placid Kindata treats everyone as equals. Everywhere he goes, people literally flock towards him, with smiles on their faces. He jokes with them and makes everyone laugh. Unlike most other priests, he doesn’t own a car. He is poor. He is solely interested in uplifting local people – whether they are Catholics or not.

With a degree in business administration, Father Placid has managed Mama Doctor’s program to rehabilitate epileptics socially.

With his instruction, the epileptics are no longer treated as social outcasts. They are paid for agricultural work, enabling them to lead happy, independent lives. Having grown up in rural circumstances, Father Placid knows how to farm and how to take care of livestock.

When I arrived at Mahenge in July, the Bishop of the Diocese had just informed Father Placid that he was to be transferred immediately to the most remote and backward area of the Diocese, at Luhombero. Father Placid did not dare utter a single word of protest, but he was deeply troubled. I met with the epileptic workers who depended on him. They were crestfallen and frightened. What was going to happen to them?

Father Placid’s replacement – who I also met – is a very fine, young priest from a prominent family. He confided he knows nothing about agriculture. Upon taking over the parish, where Father Placid had just overseen the construction of new church, Father Placid’s successor was further rewarded with a trip to Rome for two months.

They say God works in mysterious ways. Well, so does the Catholic Church. I could not fathom it. And I dreaded returning to Tsawwassen with this news.

Placid and I borrowed a vehicle to get us to Luhombero. I wanted to see the place. Mama Doctor had already told me about it. She had visited Luhombero several times in the late 1960s when it was regarded then as the Pluto of all parishes.

As we jolted our way along the pot-holed road, with two nuns in the back seat, one of the wheels fell off. We didn’t have a spare. Several wide-eyed children appeared in the darkness, staring in silence. I gave them a kite. There we all were, stranded in the moonlight, out of cel phone range. And I felt strangely calm and happy.

Sisters Ponsiana and Maxensiana were companions in the moonlight when the tire fell off.

At Luhombero, there’s a big church and not much else. The accommodations are primitive. Maybe grim is a better word. I became privy to Father Placid’s feelings. Gradually I learned the story of his life. And we explored. Atop one hilltop, teenagers silently gathered around a rough-hewn wooden bench, with their right arms extended, holding aloft their cel phones, as if praying to the heavens, hoping to catch a signal from the outside world.

Rather than feeling uncomfortable in Luhombero, I felt I was joining the rest of the planet. Placid and I became friends. We decided Luhombero had to be seen as an opportunity for change, for transformation.

Back in the progressive independence days of Julius Nyerere, who led Tanzania out of colonialism from 1961 to 1985, the government had tried to develop the Luhombero area as a hub for wildlife tourism. The hazardous road was impassable during the rains; there was also no infrastructure at Luhombero, not even a store; so the scheme failed. But, as a result, Luhombero is blessed with a plethora of discarded buildings.

Two wells can be refurbished and there is an excess of flat land. With his business acumen, his rural cultural background and his skills as a farmer, Father Placid is confident he can upgrade the living standards for everyone and ultimately employ more recovering epileptics in Luhombero than he had done in Mahenge . . .

If he only had a tractor.

Help Luhombero

Consequently, Vancouver Island website designer Sharon Jackson and I have made a public platform called Help Luhombero to empower Father Placid to generate change.

Consequently, Vancouver Island website designer Sharon Jackson and I have made a public platform called Help Luhombero to empower Father Placid to generate change.

It’s not rocket science. With multiple, small donations – via Paypal or with a credit card – collectively people who are familiar with BC books and authors can “Adopt a Village” in Africa.

If you have read BC BookWorld for free over the last 30 years – or if you have visited ABCBookWorld for free, or read The Ormsby Review for free, or enjoyed book news from BCBookLook for free – well, it takes only one minute to send a small donation.

Visit the website to learn more.