People all over the world will take part in the International Day of Prayer for the Persecuted Church this Sunday (November 10). Local author and advocate Reg Reimer tells how he became part of the movement to protect believers whose freedom, and lives, are threatened.

People all over the world will take part in the International Day of Prayer for the Persecuted Church this Sunday (November 10). Local author and advocate Reg Reimer tells how he became part of the movement to protect believers whose freedom, and lives, are threatened.

Advocacy for persecuted Christians in Vietnam has been my passion for over 30 years. It has also been a constant activity even as I have served various international ministries. It was not an accidental development.

As a boy I heard my father recount with horror his first living memory. As a five year old he witnessed the assassination of his grandfather and uncle in their home by anarchistic marauders who terrorized southern Russia (now the Ukraine) in the wake of the 1917 Communist Revolution.

What followed the shooting was equally memorable. His devout grandmother came out of hiding, fell on the bodies of her husband and son, screaming, “There is no God, there is no God!” The next day the two men were hastily buried and the entire village fled.

This part of our family story made a deep impression on me, even though I was to learn that religious persecution was not the whole story. As in other persecutions, the causes were complex.

To learn more I studied Russian history at my university in the 1960s. This led me to discover the remarkable work of Michael Bourdeaux. Through a journal published by Keston College in the UK, he tirelessly documented the terrible persecution of Christians in the USSR during the Soviet era.

In 1966 our family went to serve in Vietnam as missionaries. Eight years later, after the Communist victory (1975), we were forced to leave the country. Both my family history and my study of the ruthless persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union told me Christians in Vietnam would face very hard times. Indeed, they did.

In 1966 our family went to serve in Vietnam as missionaries. Eight years later, after the Communist victory (1975), we were forced to leave the country. Both my family history and my study of the ruthless persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union told me Christians in Vietnam would face very hard times. Indeed, they did.

Shortly after the fall of Vietnam to Communism, we were assigned by our mission organization to Thailand to work with refugees fleeing newly Communist Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Our contacts with arriving refugees, among them Christians, gave us a window into the dark decade which had descended on these countries. It was a story of deep deprivation for all – and heavy persecution for Christian believers.

We gave ourselves to help those fortunate enough to survive perilous flights across treacherous land borders and pirate-infested rough seas. Refugees came regularly but in numbers manageable by the Thai government with the support of mostly Christian NGOs, until late 1979 that is. Then Vietnam, angered by attacks on its border villages by the Khmer Rouge, overthrew the murderous Khmer Rouge regime. Hundreds of thousand of desperate, starving and dying Cambodians poured into Thailand, for a time overwhelming us all.

In July 1980, over breakfast coffee, I read in the Bangkok Post an advertisement for the first Western group tour to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. I jumped to join. There were eight of us and an embarrassingly impolite British guide. However, not one of us was a tourist. Among us were a journalist, a Red Cross representative, a couple of intelligence agents and a missionary.

Sunday was a day off on our highly supervised tour. Our government minder looked puzzled when I informed him I wanted to worship with Christians, but he did not say no. There were a few hundred people at worship when I arrived at the large evangelical church on Tran Hung Dao Boulevard. I recognized a significant number of friends and acquaintances. None acknowledged me!

During the distribution of the communion elements, I managed through a server to exchange notes with the pastor who preached that day. I knew him well. His return note to me said simply, “Come to the side street beside the church at dusk and follow the directions of an old lady who will be watching for you.”

When I came as instructed, I was guided through the back door of the big building, up narrow stairs into a room where four pastors awaited me. After an emotional reunion, I listened as they poured out their hearts concerning the suffering of persecuted Christians throughout the country. Many leaders were in prison, some had died, and many shepherdless Christians were living in fear. When the room fell silent, I asked, “What do you want me to do?”

Immediately, the president of the Evangelical Church of Vietnam, the Reverend Doan Van Mieng, said, “Please, raise our voice in the outside world; we cannot speak for ourselves!” This request proved to be a seminal moment. It burned into my mind and heart. I knew then and there that I had received another calling, though I had little idea how consuming and complicated it would become.

The very next day, I ‘accidentally’ spotted the wife and children of Pastor Mieng’s son, a close friend of mine, who was in prison. They stood on a low balcony of a flat as I passed by in a pedicab. Our eyes met, but the situation was such that I could only move my hand in acknowledgement. That moving moment contributed to my first response. I knew I must help the families of those in prison, so I began to raise money for this purpose.

To my consternation, neither my own mission nor a relief organization that I served were willing to pass these donations through their books. They deemed this activity ‘political.’ I knew beyond a doubt that I was obliged to help the suffering families and contribute to the care packages they were occasionally allowed to give their prisoner husbands and fathers. I found ways. That experience foreshadowed other evangelical ambivalence and misunderstanding about advocacy that I would encounter.

During the 30 years since that first visit, I have made at least 100 more to Vietnam. I have learned, often by trial and error, what it is required of an advocate for the voiceless. I have also come to understand that what I have learned in Vietnam has application for others who would understand advocacy or wish to become advocates.

Gradual improvement

Let me paint the religious liberty situation in Vietnam. The first decade in a Vietnam united under Communism (1975–85) came to be called ‘the dark decade.’ All Vietnamese ethnic minority pastors were imprisoned, their churches disbanded.

Ethnic Vietnamese Christians also suffered hardships and imprisonments. Many Christians ceased gathering for public worship. Small denominations voluntarily were subsumed into the largest, the Evangelical Church of Vietnam South. The situation improved marginally toward the end of this period. Importantly, through intense prayer and a spiritual revival many fearful Christians were emboldened.

From 1986 to 2004, religion was ruled in Vietnam by a series of decrees. In 1986 Vietnam announced a period of Doi Moi or ‘Renovation,’ which included the decision to abandon much of Marxist economics and to engage the outside world for trade. This political change of perspective helped expose and modestly ameliorate some of Vietnam’s harsh policy and practice regarding religion.

This period also saw the birth and dynamic growth of the house church movement. Denominations multiplied. In Vietnam’s Central Highlands and Northwest Mountainous Region, where Protestant Christianity virtually exploded among ethnic minorities in the 1990s, the authorities devised comprehensive plans to ‘eradicate’ the growing faith, including government programs of brutal, forced renunciations of faith.

The third period may be dated from 2005. Strong international pressure helped usher in some new religious legislation. One policy change promised a greater measure of freedom by registering churches. The new laws also made illegal the large, systematic measures taken to force renunciations of faith. Mercifully they were stopped.

By 2010 the nine church organizations that were able to convince the government they had roots before 1975 achieved registration. However, dozens of other organizations representing many hundreds of congregations remain unregistered. The situation has improved, but all churches, registered or not, currently remain under close scrutiny by Vietnam’s large religion management bureaucracy.

Vietnam’s Christians affirm that international advocacy was the biggest contributor to positive changes. They plead for it to continue. In spite of it all, the Protestant movement grew from 160,000 in 1975 to an estimated 1.4 million by 2010. That is 900 percent growth in 35 years! In Vietnam it is more accurate to say that persecution came (and still comes) to where churches grow, rather than that persecution caused growth.

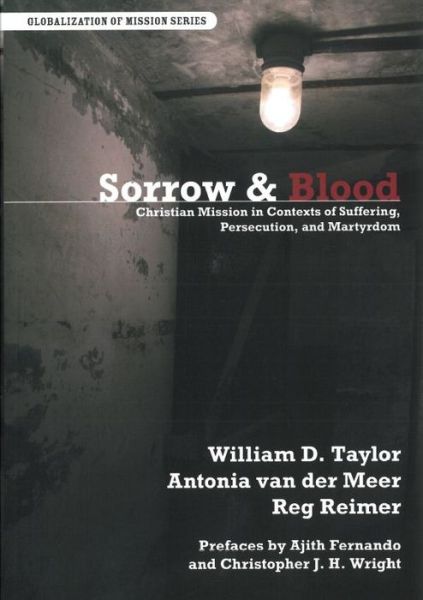

This article is excerpted by permission from Sorrow and Blood: Christian Mission in Contexts of Suffering, Persecution and Martyrdom. Reg Reimer, who lives in Abbotsford and attends Sevenoaks Alliance Church with his wife LaDonna, edited the book, along with William Taylor and Tonica van der Meer. In 2011 Reg published the acclaimed Vietnam’s Christians: A Century of Growth in Adversity.