Despite the cold, rainy weather, Burnaby Mountain protestors (protectors) continue to make the case against the Kinder Morgan pipeline. Photo by Letizia Waddington.

People of all ages and backgrounds continue to get arrested while protesting the work on the Kinder Morgan pipeline on Burnaby Mountain. The whole event raises serious questions for Christians.

The protestors are clearly operating out of deep conviction, but breaking the law is serious business – especially in Canada, where the tradition of civil disobedience is not as well-established as it is south of the border. There, the Civil Rights movement and opposition both to nuclear weapons and the Vietnam War established as a legitimate form of last resort protest. Sometimes Christians even led and blessed those movements (remember Martin Luther King).

The modern model for passive resistance as a form of political action is Mahatma Gandhi, in his leadership of the Indian independence movement. And he made it clear that the ultimate model for innocent people who choose to suffer in a righteous cause was Jesus.

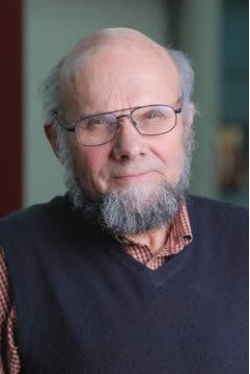

Regent College prof Loren Wilkinson has written on environmental issues for decades – and was arrested while protesting in Clayoquot Sound just over 20 years ago.

More recently, Anabaptist theologian John Yoder, especially in The Politics of Jesus has made a strong case that the highest form of Christian behaviour in a corrupt system is to live as righteously as one can and let the system show its poverty by the way it treats such inconvenient righteousness.

But is the system which is (apparently) bringing so much prosperity to Canadians through extraction of Alberta’s oil a corrupt system? Is there anything unrighteous about our participation in that system when we fill up at the pump? Is there anything contrary to the kingdom of God in the attempt to get that oil to markets and refineries?

Apparently not – especially if you survey the abundant and elaborate cases made by those promoting the pipelines. (If you need convincing, just google Kinder Morgan Pipeline, Northern Gateway Pipeline or Keystone Pipeline.)

My own brush with civil disobedience was 20 years ago, when my wife, Mary Ruth, and our daughter and I were among the 800 or so people arrested in the protests about logging in the Clayoquot Sound area on Vancouver Island. I still feel that was the right thing to do. I’ve written extensively about it elsewhere (see below for one article published in Radix).

I must say that if those protests and arrests were appropriate then, in attempting to change BC logging practices (and in that they were partially successful), such action is far more appropriate now, and the issues even more important.

This whole topic is way too big and complicated to talk about in a few paragraphs, but let me make a few points which might help us all as we think and talk about the Kinder Morgan protests, the pipelines, Canada’s increasing importance as an oil producer, the health of the planet and the relevance to all of this to our frequent prayer: that God’s kingdom will come ‘on earth’ as in heaven. Perhaps these points will give us a framework for thinking more wisely about how we live – and whether we should protest the protestors, support them or join them.

The issue

First, some details about the immediate issue:

What we call the ‘Kinder Morgan’ pipeline is already built, and has been in existence since 1953. It is at present the only pipeline supplying both crude and refined oil to the west coast of North America, and is more helpfully known as the ‘Trans-Mountain’ pipeline.

The Kinder Morgan company, which now operates the pipeline, was founded in 1997 by Richard Kinder, formally CEO of Enron corporation, and is the third largest energy company in North America. All of us in BC regularly use products which are transported across the mountains from Edmonton via this pipeline’s 715-mile length and 24 pumping stations.

The immediate cause of the current crisis is the decision by Kinder Morgan to build a parallel pipeline which would nearly triple its current volume of 300,000 barrels/day to over 890,000 barrels/day. The pipeline currently ends in Burnaby, but much of the increased oil volume will go to Asia via tanker, and for this it is necessary to get the oil to the deep-water ports on Indian Arm at the end of Burrard Inlet. The most efficient way to do this is to tunnel under Burnaby Mountain. The workers whose activity is being protested are doing surveys preliminary to the digging of such a tunnel.

The objections

There are three levels of objection raised by the protestors.

The first is against the immediate – and legally dubious – right of Kinder Morgan’s workers to disrupt and damage Burnaby’s parkland. The city of Burnaby appealed to the B.C. Supreme Court to have the survey work stopped, but that appeal was rejected.

The second objection is against the potential damage which spills from the pipeline, and the tankers which it feeds, might do to the environment, both on land, through national and provincial parks and, especially, in the waters around Vancouver, Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. This risk – despite assurances to the contrary – is very great.

But the third level of objection is the most important: it is a recognition that the Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion is part of a major move by the Canadian government to use the very dirty bitumen from the Alberta tar sands in order to become a major player on the world’s energy scene.

Tar sands development continues unabated, largely fueled by investment from countries (like China and the US) which have, like Canada, an inexhaustible demand for oil. But the more productive these oil fields become, the greater the pressure to find ways of moving the oil to markets.

At present, three other major pipelines are in the works: Northern Gateway, directly across the mountains to the port in Kitimat; Keystone, which would angle southeast across Canada and the U.S. to ports and refineries on the Gulf Coast; and Oil East, which would cross Canada to New Brunswick. The more these pipelines are built, the greater the chances that the vast pools of tar-sands oil will be extracted and used.

Thus the biggest problem is not the threat of oil spills; the biggest problem is that the oil will reach its destination and be used, thus increasing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.

There is no question at all that the CO2 content of the atmosphere has increased from around 270 ppm (parts per million), in pre-industrial times, to over 400 ppm at present. And there is overwhelming scientific consensus that the increase is caused by human activity and is leading to rapid, dangerous climate change.

Consequences are overall global warming, rising sea-levels, more extreme weather and rapid decline and extinction of many living species. Ironically, it is the poor who are most vulnerable to these changes. A rough guess of sustainable levels is 350 ppm – but the level is now past 400, and increasing by 2 ppm per year, with no realistic indication by the governments of the biggest producers that they are going to seriously reverse that trend.

Perhaps even more serious than global warming – and even harder to deny – is the fact that the increase in atmospheric carbon has led to an increase in ocean acidity, which threatens every form of ocean life which depends on calcium carbonate shells – ranging from coral reefs to edible shell-fish like clams and oysters to the diatoms which are a crucial part of the marine food chain.

God’s good creation

To protest the Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion is thus to make at least a small statement in favour of the continued health of God’s good creation.

The whole affair is complicated by the fact that professed Christians – including our current Canadian Prime Minister – are among those who are most likely to deny the reality of human-caused atmospheric change, most suspicious of science and most likely to be in support of ‘business as usual’ in the oil industry.

A good indication of how this attitude plays out in real politics is the story of Bill C-38, which was passed without objection by the Conservative majority in Parliament. It was 425 pages in length, and contained a very large number of constitutional amendments, most of them related to removing environmental regulations.

It repealed Canada’s agreement to the Kyoto Protocol; it dissolved the National Round Table on the Environment and Economy; it reduced the number of lakes and rivers protected by the Navigable Waters Protection act from 2.5 million to 159; it removed from the protection of the Fisheries Act any fish habitat that was not clearly part of a commercial fishery; finally, ironically, it terminated BC’s oil spill response centre – all without much notice or objection by the Canadian public.

Green party MP Elizabeth May, operating from a very different understanding of what it means to be a Christian in politics, is perhaps not exaggerating when she calls the government under the current prime minister “an elected dictatorship.”

None of these facts answer directly the question of whether a Christian should support the Kinder Morgan protests. However, if we take seriously that creation is good; that we humans have a responsibility to care for it; that Christ in whom “all things hold together” has chosen to reconcile “all things to himself” – then it is easy to understand why some feel that protest and arrest is perhaps the best way to express dismay at the ignoring of these truths.

A challenge

Have Mary Ruth and I joined the protesters – and those arrested – on Burnaby Mountain?

Not yet. But we take very seriously an open letter widely distributed by many well known and thoughtful people – Wendell Berry, Bill McKibben, David Suzuki, Naomi Klein and James Hansen (formerly chief climate scientist for NASA), to name a few – a couple of years ago, just before a key U.S. decision involving the Keystone pipeline. Mary Ruth and have included it since in a course we teach on ‘Wilderness, Technology and Creation.’

It is highly relevant to what is happening on Burnaby Mountain, so I close by quoting a few passages:

The short version is we want you to consider doing something hard . . . coming to Washington in the hottest and stickiest weeks of the summer and engaging in civil disobedience that will likely get you arrested.

The longer version of their letter – after talking about the undeniable fact of global warming and the environmental damage of oil sands development, and pipeline spills – gets directly to the main reason to oppose pipelines like Keystone, Northern Gateway and the Kinder Morgan expansion:

These local impacts alone would be cause enough to block such a plan. But the Keystone Pipeline would be a 1,500 mile fuse to the biggest carbon bomb on the continent. . . . How much carbon lies in the recoverable tar sands of Alberta? A recent calculation . . . puts the figure [of increased atmospheric carbon] at about 200 parts per million. Even with the new pipeline they won’t be able to burn that much overnight – but each development like this makes it easier to get more oil out. As the climatologist Jim Hansen (one of the signatories to this letter) explained, if we have any chance of getting back to a stable climate, “the principal requirement is that coal emissions must be phased out by 2030, and unconventional fossil fuels, like tar sands, be left in the ground.” In other words, he added, “if the tar sands are thrown into the mix it is essentially game over.” The Keystone pipeline [along with the Kinder Morgan expansion, Northern Gateway, and Oil East] is an essential part of the game.

. . . it’s time to stop letting corporate power make the most important decisions our planet faces.

We don’t have the money to compete with these corporations, but we do have our bodies, and beginning in mid-August many of us will use them. . . . We’ll do what we can.

And one more thing. We don’t want college kids to be the only cannon fodder in this fight. . . . Now it’s time for people who’ve spent their lives pouring carbon into the atmosphere (and whose careers won’t be damaged by an arrest record) to step up too. . . . We think it’s past time for elders to behave like elders.

. . . We know we’re asking a lot. You should think long and hard on it, and pray if you’re the praying type.

I suspect most of the readers of Church for Vancouver are the praying type. Neither the words of that letter nor my thoughts in this article can or should persuade you to break the law. But I hope they can help us all better understand how to live in such a way that the gospel is good news for the whole creation.

***************************************************

The following article was published in Radix, a journal based in Berkeley, California, about 20 years ago. It’s shamelessly autobiographical, but it asks, and partially answers, many of the questions about the Christian and creation in the context of this part of the world.

Early one Monday morning last September my wife and daughter and I were arrested at the entrance to the Kennedy River logging road near Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island in British Columbia. Later that morning we were charged with criminal contempt, and released. Our trial is in April. We will be tried for refusing to obey a court order telling us to clear the road so logging crews could go to work.

By that time of the summer there was nothing particularly unusual about our action – people had been getting arrested at the Clayoquot Sound blockade almost every day since late spring (a total of over 800). What was unusual is that we were part of a very small minority of those arrested who linked their action to their Christian faith.

In the evangelical sub-culture, to be arrested protesting abortion is laudable, if ia bit rash (I support and admire those who have taken that stand). But to be arrested protesting bad forest policy is seen by many as making dangerous compromises with anarchy, pantheism and political correctness.

Why worry about trees?

So we were something of a bewilderment to both sides: to environmentalists, who are suspicious of Christianity because of its dangerous idea of ‘dominion’ and to evangelical Christians, who are suspicious that most environmentalists are really thinly-disguised pagans.

There is reason for the suspicion on both sides, and our choice to be arrested plunged us into a whirlpool of conflicting spiritual, ideological and political currents. Was that choice wise? Was it right? Was it Christian?

I am thankful to Radix for asking me to make some sense out of our decision on the Clayoquot, issue, which is the local version of a worldwide rethinking of how we treat the earth – a rethinking which is going on within evangelical Christianity as well.

But I can’t make sense of my own decision to be arrested without talking also about lots of other things: the state of the west coast forests, the way my own life has been intertwined with those forests, and the overarching truths that the earth is the Lord’s, that the gospel is good news for the earth, and that we have all too often turned it into bad news.

* * *

The temperate forests on the northwest coast of North America sustain more living matter than any other ecosystem on the planet: on average, an acre of rain forest in Oregon, Washington or British Columbia holds twice the tonnage of living things as an acre of rain forest in South America.

That extraordinary treasure of living stuff (whether measured in cubic meters, or board feet or tons of pulp) is the main reason why old-growth forests on the west coast are regarded with something close to reverence by both environmentalists and the forest industry. To the industry, the old forests (available for a minimum stumpage fee on public land) yield vastly more profit than any tree-farm. To some environmentalists on the other hand, an intact forest is a library of genetic information holding answers to questions (including questions about forestry) which we have not yet learned to ask. To others, the forests are nothing less than outdoor icons for a religion of Gaia – goddess earth.

This wealth of the west coast forest is also one of the reasons why more of the rain forest is gone in North America than in South America. In 1990 in Oregon and Washington, only about 13 percent remained; on Vancouver Island, about 36 percent (exact figures about a project so vast as the deforestation of a corner of the continent are impossible to obtain). The future of that remaining fraction is the cause of one of this region’s biggest arguments.

On one side are the forest companies (who say they need access to the last forests in order to provide a profit for their shareholders) and the loggers (who say they need the forests in order to have a job.) On the other side are the environmentalists who argue both for a new kind of genuinely sustainable forestry, and for leaving a few watersheds undisturbed as examples of healthy forest ecosystems (at least until we know enough about the forest to be able to use it without permanent damage).

Somewhere in the middle are the governments (though historically they have been much closer to the companies), torn between the undeniable dollar value of the forest industry, and the equally undeniable vote-value of a constituency which with each election seems to contain more environmentalists, all of them grumbling about logging in old growth forests. It is a nasty and complicated argument, with plenty of studies, statistics, deceptions and exaggerations on both sides.

On the whole, Christians have stayed out of the fight, a stance which amounts to a tacit siding with the forest industry (since status quo policies are steadily reducing and fragmenting the remaining old forests). But the alternative – to side with the environmentalists – is deeply unpalatable to most Christians.

For the ‘environmental movement’ itself is becoming more and more religious: a ‘deep ecology’ which calls not only for new policies, but for spiritual renewal. However, the preferred spiritualities draw on paganism, pantheism, shamanism, Buddhism and goddess worship. So, not surprisingly, most Christians would rather keep their distance from such a crowd.

The argument over forestry is taking place all up and down the northwest coast, but it is most intense in British Columbia. Because western Canadians are, on the whole, at least a generation closer to the frontier than Americans, they have shared the frontier illusion that resources are unlimited. There’s more at stake here: there’s also a need to change attitudes in less time.

I grew up in Oregon, did my first serious thinking and writing about the relationship between Christianity and creation in Washington, and for the past 13 years I have lived in British Columbia. When we came here in 1981 I was moved by the emptiness of the country to the north: standing on a beach near Regent College (the graduate school of Christian studies where I teach) I could look at the glaciers of the Tantalus range beyond Howe Sound and realize that from where I stood I could travel to the arctic circle and cross (at most) two paved roads. Most of that land was forested, and I took some comfort in the vastness of the remaining Canadian forests.

Then, slowly, I began to learn about B.C.’s forest policy.

I stumbled on the cornerstone of that policy while engaged in my favourite form of procrastination, studying maps of mountain wilderness in the UBC map library. As I worked up the coast (via maps and imagination) I crossed mile-deep fjords, great icecaps, valley glaciers, wild rivers – and steep slopes and level valleys of deep green which I knew to be forest. On most of those superb maps there was no road or town or any boundary marker – except dotted lines that ran, in a grid, over the valleys, the mountains, the glaciers. Neatly printed by each was the label ‘Tree Farm License . . .’ and a number.

Thus I learned of the Tree Farm License system, which was hastily instituted shortly after World War II, and which assigns most of the productive forest land of British Columbia (99 percent of which is ‘crown’ or public land) to a particular logging company to manage.

Though it may look and feel like wilderness, the ultimate fate of most of B.C.’s coastal forest is to become a tree farm. The price to the company is minimal. The total return to the public per cubic metre of wood cut on crown land in BC is 2 cents. By comparison, the return to the public in U.S. National forests on the BC border for the same amount of wood is over $10. With such vast reserves available for so little cost, it is easy to see why stewardship has not been a high value in BC forestry practice.

* * *

A little over five years ago we moved to a farm on Galiano Island, half-way between Vancouver and Vancouver Island. Over half the island was owned then by MacMillan Bloedel, BC’s largest forest company, the same company which had control of many of the Tree Farm Licences in the old-growth coastal forest. The 800 Galiano islanders were generally happy to have the company as a neighbour. The island had already been logged at least once; it is a superb place to grow trees; the company was cutting at a reasonable rate, and there are worse things than living next to a well-managed tree farm in the Gulf Islands.

But shortly before we moved to the island the company drastically accelerated the rate of logging, announcing its intention to ‘rejuvenate’ its holdings – which meant logging it all and starting over. At the same time, it let it be known that its real plan for the island property was development: a resort hotel, golf courses and housing for 6,000 people. The plans (then only rumour) were met with something like universal horror. We thought this was a logging company.

The fight that followed was long and complicated, and is far from finished. Most of the islanders took the position that the island ought to remain a tree farm and a small rural community, rather than be turned into a series of golf courses and suburbs. They undertook to buy the land, hold it in trust and continue to manage it as a productive forest.

But the company was not interested in the idea of community purchase or continued forestry. It was clear that their primary concern was not good forestry (or even bad forestry), but the obligation to get a maximum return on investment. They saw the immensely greater value of the land as real estate, and saw no good reason to treat the land as a tree farm.

Eventually they abandoned their large development plans and placed their land, lot by lot, on the open market, advertising it is “an investment in paradise.” The island government countered by passing zoning by-laws prohibiting residential development on land zoned for forestry (as all of the company’s Galiano land was). The company responded by suing the island government for restricting their use of the land. They won the suit; the bylaws were overturned. At present, though, that decision is being appealed, all of the forest land has been reassessed at residential rates and the forest land is being rapidly subdivided.

The immense irony of the situation is this: the company which had, over the decades, received the most benefit from the privilege of cheap stumpage on public lands, was using the courts to ensure that its own forest land would be removed from forest status. I was a board member of the conservancy association which had tried to negotiate a community purchase of the land, and like most of the islanders, had spoken in favour of the by-laws keeping the land in forestry. The utter failure of company and courts to see the value of a genuinely sustainable forestry had a lot to do with my illegal presence on the Kennedy River logging road last fall.

For while the MacMillan Bloedel lawsuit allowing abandonment of forestry on their own lands was dragging through the courts, on the west side of Vancouver Island – and in Victoria, B.C.’s capital – another long argument was drawing to a close.

The west side of Vancouver island faces the open north Pacific, and is a beautiful – and largely inaccessible – coastline of long white beaches, rugged headlands and island-dotted bays and inlets. About half way up the island lies one of the largest and – and most accessible – of these networks of sheltered water, Clayoquot Sound.

Several large, heavily forested islands are in the sound, and a broad band of forested hills and valleys link the sound with the glaciated peaks in the centre of the island. One by one most such areas on the west coast have been logged. Clayoquot Sound was the last large relatively intact area on the coast. A variety of claims and protests – some from local native groups, some from an environmentalist organization called Friends of Clayoquot Sound – had held up logging in the area. A government study promising a final solution had been underway for several years.

In April of 1993 it released its conclusions, which were a delight to the forest industry and a shock to everyone else. Although it called for preservation of roughly half the area, most of what preserved was rock, bog or already protected; of the marketable timber in the area, more than 80 percent was slated for logging in the next few years. The last hope for a substantial coastal forest reserve on the island was gone. The logging began late that spring. So did the blockades – and the arrests.

And the company which called for the court orders which cleared the road to give it access to the public forests was MacMillan Bloedel, the same company that on Galiano island was suing to take its own land – long taxed and zoned as forest – out of forest production forever.

* * *

By late September the blockade on the Kennedy River logging road had become as predictable as a well-scripted drama. Shortly before 4 am an accordionist started playing in the darkness of the Clayoquot ‘Peace Camp’ (he played ‘Roll Out the Barrel, Let’s Have a Barrel of Fun’); people awoke in various tents. The moon was down and it was pitch dark. We dressed, groped and stumbled to cars, where we joined a long cavalcade to the road entrance; we piled out of the cars; some people started a fire to the side, and served a breakfast of rolls and tea; we massed on the road; at about 6:00 a truck approached with spotlights and two video cameramen; they proceeded to film everyone on the road; shortly afterward someone with an amplifier started to read a court injunction to clear the road; everyone not planning to get arrested (most people there had been arrested – once) cleared the road, leaving 13 of us; then a group of police arrived. With great politeness they handed us a copy of the injunction, asked if we would like to walk or be carried to the waiting bus. (We walked; some were carried.)

I can’t separate my presence on the road from my own past.

I grew up on a bend of the South Santiam River in Oregon’s Willamette valley. When my parents bought the farm at the end of World War II it was a few small fields scratched out of big old timber: quick-growing cottonwood, some huge mossy maple and ash – and a central grove of tall Douglas fir. The 200 acres of the farm was a small world to a young boy, and I grew up in the shadow of old trees. The woods were full of cow trails, for our cattle used the forest like a pasture. I roamed for hours. Once, I remember finding, with awe, a single trillium, like a white emblem of the trinity, in the deep shade under the firs. Another time, I gathered a fistful of violets growing in the deep moss beneath maples and brought them to the house. Neither the fir, the maple, the violets nor the trilliums are there any longer.

For it was our job, our vision, our dirt-poor necessity to turn the forest into a farm: to reduce the trees to salable logs, the land to tillable acres. Some of my very earliest memories are of following the clanking Cat down into the woods in the dust behind the trailing chokers – or crouching in shelter while my father dynamited stumps.

As I grew up, most of my summers were spent divided between farming (hoeing corn, shovelling manure, moving irrigation pipe) and logging (trimming; bucking, setting chokers, loading). The logging crew was my father, on the Cat; my older brother, who drove an ancient truck; and myself. Usually the saw would break, or the cat would throw a track, or the truck would develop engine trouble on the way to the log pond in Salem. But sometimes things went right, and some of my most satisfying memories of physical work come from those days.

On a good day we could get three loads off to the mill, loads that were sometimes worth as much as a hundred dollars each: 300 dollars a day, back when profits from the whole farm might not add up much more than a thousand dollars a year. Logging meant money to our dirt-poor family; it was only on log money that we could rise above the subsistence level of farming. So I still have it in me to look at the tall gray cylinder of a douglas fir trunk, guess the board feet and figure its worth.

On the farm, of course, the valuable trees were the big old ones: close-grained douglas fir, six feet through, 60 feet to the first limb: money in the bank. But though we planted new trees, we weren’t under any illusion that they would replace the others in our lifetime. Increasingly we logged the quick-growing cottonwood for pulp, leaving the dwindling grove of old-growth fir like money in the bank. But we fell the last old firs the summer before I went to college. And when I boarded the Greyhound bus for the three-day trip to Wheaton in 1961, all that was left of the big fir trees was eight $100 Traveler’s Checks buried deep in my suitcase.

One summer I worked with my cousin (who worked for my uncle), surveying logging roads into various national forests in the Oregon coast range and the Cascades. It too was good work: we were well ahead of the logging crews, and sometimes spent days in deep, fragrant woods, clambering over mossy, rotting logs as tall as ourselves. Water dripped from deep moss and maiden hair ferns; we were surrounded by life. It was a wonderful summer job.

At the end of the day we hiked easily back out, downhill, along the way we had cleared with machetes. The stakes we had carried on the way in were now driven to mark the linear route, and (up the slope) the depth of the cut. Sometimes the fallers had started behind us, clearing the right of way. I knew the value of good fir, and appreciatively estimated the footage in huge butt logs, still dripping pitch. The trees were fragrant in their death, the cools shadows gone in the afternoon sun. Sometimes I caught myself thinking: do I want to do this. Should there even be a road here. But it was a wonderful summer job.

In the following years, in Oregon, Washington, BC – at first from mountaintops, then, increasingly, from airplanes descending toward Portland, Seattle or Vancouver – I watched the clearcuts spread, and spread: the forested valleys become valleys of slash and erosion. I watched the new trees grow – at first, spontaneously, later, from planting: but slowly, slowly, never matching the rate of the cut (and never the health and diversity of the original forest). And at some deep level I remembered the vanished fir woods, the ‘money in the bank’ of the boyhood farm – and the lost trilliums and the maidenhair ferns.

At college I assumed I was preparing to be a foreign missionary. How else could one serve God? But I kept being drawn to literature, philosophy, theology. Looking back, I see that one thread linked everything I studied: what does it mean that we are creatures? What is the place of creation in all of this? In the Christianity of my childhood, salvation had meant one thing: escape from Hell.

I remember an evening evangelistic service in the community Sunday school that met at Santiam Central, my school. A couple of dozen people (regulars, all) sat in the desks to hear the preacher. Tonight he has brought “an object lesson”: a pie-plate filled with yellow sulphur, which he lights. It burns in a blue molten pool and he passes it up the aisle. The air in the room is barely breathable. “That’s brimstone,” he says. “That’s eternity without God. Don’t touch it – it eats like a cancer.”

Not even now – and certainly not then – would I exactly disagree with him. But the incident underlines the overwhelming picture I had of salvation: all the earth, myself included, under the threat of imminent, fiery destruction. The ‘good news’ of the gospel was that there was a way of escape from that fiery death soon to overtake all creation. It was good news for a few of us; it was bad news for everything else: especially things like trees, which didn’t have a chance.

As my sense of the splendour, beauty and wild complexity of creation was gradually growing, my emerging theological understanding was reinforcing in me the idea that it was all bound for destruction – fairly soon. I felt bad for the mountains and the forests, but my soul, at least, was safe.

A good part of my education has been concerned with broadening that understanding of redemption; a good part of my life has been spent trying to communicate that fuller view, trying to spell out what it means for the created world. But the theology I grew up with – that the created world is a short-term backdrop for a human drama in which the rest of creation has no place – is still flourishing.

In Seattle I recently gave a lecture in which a pastor in the audience objected to my saying that creation had a place in the redeemed order. In a later letter he articulated his views very clearly:

Christ’s redemption is always in purchasing the chosen or elect from their trespasses. . . . the redemption of the earth from its groaning will be its vaporization and replacement. Its value is in providing our habitation; it is a variable, we are the constant with God. Praise the Lord that his promise is made so clear to those that want to hear.

* * *

The afternoon before our arrest a dozen or so Christians from the Vancouver area had arrived and set up camp; we joined a hundred or so others at the Clayoquot Peace Camp in the desolation of a clear-cut valley. The once-forested valley was a bare, dusty amphitheatre, littered with burnt-out stumps and bits of old cable, softened now with fireweed. Some of our group had arrived early enough to attend a civil disobedience workshop led by a genial white-haired woman who identified herself as a witch, and who carefully spelled out the guidelines of the place: no drugs, no alcohol, no violence against other beings, all decisions made by feminist principles of consensus.

In the hot afternoon a girl was carefully getting her face painted in black, yellow and blue. The ambience was one of genial squalor, like a Bombay slum. It was clear we had entered a culture defiantly conformist in its non-conformity, united by something very close to religious zeal. All of us found the place oppressive – and at the same time, impressive.

We ate a free supper – well-cooked in vegetarian variety, mainly from donated produce. After supper there was a ‘circle,’ a painfully slow consensus discussion about the next morning’s action. Those who had chosen to be arrested were given special attention, and allowed to pick the theme and atmosphere of the morning’s blockade. Music? Chanting? Drums? One young college student requested that the group sing ‘Oh Canada’ while the court order was being read, but that otherwise the demonstration proceed in silence.

It struck me again as a kind of religion, with arrest as a functional equivalent to baptism. (The impression was heightened the next day when a bearded man wearing bear claws and a Krishna symbol complained that he found the silence emotionally uninspiring. “You feel better when there’s drums and chanting,” he said. It was for all the world like arguments about style of music in worship.)

Yet this motley crew, well beyond the fringes of respectability, had grasped a truth about the value of creation which most of us have lost. Because there was no way to know the vaguely-sensed Creator in their ‘earth spirituality,’they had no ultimate basis for the very care they were trying to exercise: yet they still followed a dim, deep God-given sense that we are responsible for creation, responsible to use these vanishing forests so they will still be here in their richness and abundance, for the use and delight of our grandchildren, our great-grandchildren. I kept wanting to preach Paul’s sermon in Athens: “Now what you worship as something unknown I am going to proclaim to you. . . “)

Should Christians have anything to do with such a mishmash of anarchic zeal and confused spirituality? There is no easy answer. But my own long road from the river-bottom forests of my childhood has led me increasingly to realize that the good news of the Christian gospel is more than personal deliverance from a sulphurous hell.

My teaching and writing keep circling back to the central realization: in Christ we are saved not out of creation, but for creation. It’s easy to write books and articles about that truth. But this time we decided to do more. Heidi, Mary Ruth and I decided we could no longer stay on the sidelines.

That night our group of Christians sat around a fire on a knoll above the larger Clayoquot Camp. The moon turned the ugly amphitheatre of the logged valley to a kind of silvery beauty. Some people had brought material for signs. How do you condense the rich biblical teaching on creation and redemption down to a few words?

We talked for a long time, then decided on three texts: On a big banner: “The Earth is the Lord’s”; on two smaller signs: “Creation groans . . . In Christ a new creation” and “You will go out with joy and be led forth in peace; and all the trees of the field will clap their hands.” (The next day we sang the song to the bemused pagans in the peace camp.) We made the signs, the fire died down and the moon kept on pouring light over the dry bones of the valley.

The next morning when the policemen came, Heidi, our daughter, was standing ahead of the rest of us. “Will you walk to the bus?” the officer said, in the glare of the headlights. “Yes,” she said, with a kind of joy, “I will.” At the time not even she knew she was a few weeks pregnant with her first child (and our first grandchild).

Three years earlier, at Heidi and Paul’s wedding on Galiano, Mary Ruth had read a text from Jeremiah: “I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord . . . plans to give you hope and a future.” Does that future include creation? Does it include the rich forests of the west coast – and a thousand other threatened treasures of God’s creation, of which Colossians says “God was pleased through him [Christ] to reconcile to himself all things”?

The reconciliation is ultimately God’s not ours. Yet our basic task, restored in Christ, remains: to care for creation. We are not sorry we were arrested in protest at the careless use of creation.

As we drove (in the police bus) back out the road lined with watchers I saw our candle-lit banner: “The earth is the Lord’s.” Behind us, the dark, old forest waited. To the east the sky was brightening over logged-off mountains. We went on our way to the Ucluelet jail; the vigil beside the road remained.

A little later the trucks roared into the woods for another day’s work.

[…] of this for the Christian community? In what ways could we respond. Read the full article here, and share your pondering in light of what Wilkinson argues […]

Details about next year’s March for Life (May) and LifeChain (October) will be posted here when they’re available: http://rcav.org/respect-life-2/

Here’s a bit of a different take on the issue, from a Catholic perspective: http://www.catholic.com/magazine/articles/when-is-it-okay-to-disobey

In short, “Authority is exercised legitimately only when it seeks the common good of the group concerned and if it employs morally licit means to attain it. If rulers were to enact unjust laws or take measures contrary to the moral order, such arrangements would not be binding in conscience. In such a case, authority breaks down completely and results in shameful abuse. (1903)” Catechism of the Catholic Church.

While I respect the passion of the protesters, it’s not clear to me that the law allowing Kinder Morgan to perform tests was morally illicit or unjust. Different people can disagree on that. But again, at least the non-violent protesters were willing to accept the penalty for their actions — arrest.

I wish we could see the same passion when it comes to truly illicit laws, like the ones permitting abortion. I invite the Kinder Morgan protesters and all those who sympathize with them to join us in protesting against laws permitting abortion in B.C. Every year thousands of British Columbians stand in public witness for life. We break no laws, but we let society know that, as pointed out by St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, God’s natural law supersedes man-made law.

Thank you so much, Loren, for this important call to consideration, prayer, and action. It is really encouraging to me to see this kind of discourse happening now.

I am also touched by the inclusion of native rights. Surely that is as big as the future of Burnaby or Vancouver. We need to learn from the native population these days, not just support them.

After reading this lengthy paragraph I see my protestor friends often and helped them get started on the journey taking direct action stances and putting themselves across the line of Kinder Morgan’s first attempts to overcome some simple civil disobedience measures as a kind way of saying: We don’t want your ways of making a carbon footprint in our environment with a chance of ruining our City with an oil spill that would take 20 years to clean up.

Some realized thereafter that we where already allowing Kinder Morgan to utilize our land and sea to carry out raw bitumen from Alberta through eastern B.C. to Burnaby and out to our coast Salish waterway and to sea. Form my part as an environmentalist and activist, it’s not so much what we are doing currently as how we can transition over to other natural clean ways of using free given energy from above our environment to sustain ourselves as there is only 45-60 years worth of oil left in the ground and put a permanent halt to Kinder Morgan using our water way as an exit to Asia with Canadian oil.

I am a strong advocate towards using the law and creative applications to enhance our chances for change and today we managed as a result of our persistence to put a halt on extending Kinder Morgan’s referendum stopping us from protesting on Burnaby Mountain after the drilling of the bore holes stop this weekend and all the civil charges against the protestors that crossed the line are now dismissed and dropped. Persistence is everything, while time is a factor for the truth that we need adapt quickly to if we are to save our planet surrender and clean it up!

I agree with Nelson Lee.

The best way for everyone to contribute and reduce the CO2 that is 95% caused by human activity is to revisit the Montreal Protocol. Remember how we quickly removed the McDonald’s foamy packaging?

Really appreciate this thorough article on the theological and ecological relevance of what’s happening on Burnaby mountain. As a committed Christian who did choose to commit civil disobedience on the mountain recently, I’m not sure that I could have said my convictions around this issue more articulately than you have, Loren.

I was struck by one particular absence, though. One of the fundamental arguments which persuaded me to get involved was the issue of First Nation sovereignty. As complex as this issue is in its ramifications, Canada has finally signed on to the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which requires that government and industry acquire “free, prior, and informed consent” from First Nations on any project impacting them and their lands and waters. In addition to the objections you mentioned, this responsibility has been glaringly overlooked by Kinder Morgan and the National Energy Board.

The Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, and Musqueam nations have all come out quite strongly against the expansion project. In fact, the Tsleil-Waututh are currently pursuing a lawsuit against Kinder Morgan for its failure to treat them as a sovereign nation and acquire consent. In the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the commitment so many made there to a renewed relationship with Native peoples, should we not also be asking how we might support our First Nation brothers and sisters as they struggle to protect their traditional territories, on Burnaby mountain and elsewhere?

Jason,

Jason,

You’re quite right; the violation of native rights should have been a fourth level of objection motivating protest. I was writing in a hurry and just forgot to mention that–though I suppose one reason I forgot is that in comparison to the huge violation which the very existence of Burnaby (and Vancouver, and for that matter “British Columbia”) represents, the Kinder Morgan violation is just the latest in a very long series. But the Kinder Morgan problem serves to remind us of a deep wound which can never be fully healed, and the First Nations perspective should never be left out. So thanks for your note (thanks too for being willing to be arrested!)

[…] Click here to read the “Kinder Morgan protests raise serious questions for Christians” article on the ‘Churches for Vancouver’ website. The article was written by Loren WIlkinson – a Regent College professor. […]

Your article is very much appreciated. I have worked with industry for the past 25 years as an environmental consultant and have been a Christian for nearly 20 of those years. I trust the science and feel that most Christians have failed to be good stewards of Creation. You and a few others are notable exceptions. I have thought long and hard about this, the political and industrial will to continue and even expand their fossil fuel development. Aside from God intervening, I think what is needed is for Christians to reduce their fossil fuel consumption. After all, industry will not produce what consumers are not buying – not for long anyways. I think Christians need to lead the way, like they did for hospitals, education, slavery, etc. how to get this going is my question. What can I do as a lay Christian? I hope for the Pope!

Nelson Lee, 778-317-7613