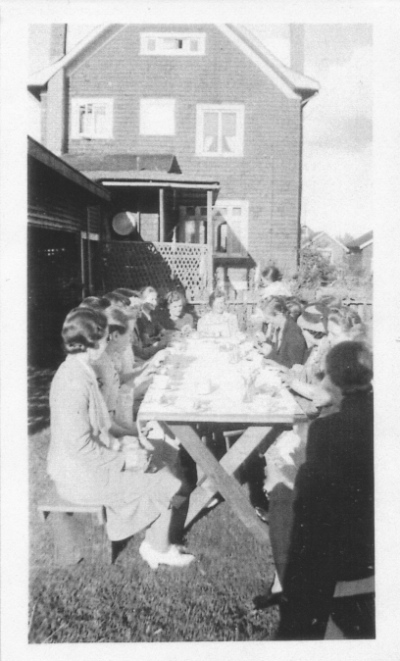

Agatha Jantzen Dyck (left) and Betty Jantzen Martens at their place of employment on East Boulevard in 1939.

Daughters in the City tells the remarkable story of ‘Mennonite Maids in Vancouver, 1931 – 1961.’

Sitting elbow to elbow in every available space and stitching patterns onto small individual squares of pre-used cotton flour sacks, a group of young Mennonite maids create a common project – a quilt. They meet as often as they can, but finding time for stitching and quilting is a challenge. They get little time away from work and need to travel by bus and streetcar to meet together. The quilt takes over a year to complete, from 1937 until late in 1938.

Who are these young women? Why are they working as maids? Where are they working? Why do they travel to this place from all over the city? Why are they stitching together in this crowded room?

Daughters in the City explores these questions and others in an attempt to preserve the significant experiences of young immigrant Mennonite women who had just recently arrived in Canada, and then were sent to Vancouver to work as maids.

Beginning with the women’s origins in Europe and Russia, this book provides an overview of their socio-cultural heritage, their attitudes towards work, the role of the church, the effects of revolution and war, the challenge of learning a new language and culture in Canada, and the burden of paying off a travel debt.

Through interviews, minutes of meetings, photographs and other historical documents, the narrative of not only one, but two Girls’ Homes for Mennonite maids in Vancouver emerges.

In the process of conducting this research, it became evident that little is known about the lives of 20th century immigrant women in Canada. Even less is known about the lives of immigrant women on the west coast.

As a first-generation Canadian of Russian Mennonite descent, I am particularly aware of the knowledge deficit surrounding the experiences of Mennonite women in their new country. Growing up in Vancouver, I heard many stories about the house where Mennonite maids gathered.

The young single women were the Mädchen (maidens) who worked as domestic workers and who still called each other “sisters” or “girls.” The Mädchenheim (maidens’ home) was part of their shared experience – the good times, the loneliness, the hard work and Thursdays off.

Many of the young Mennonite domestic servants depended on matron Tina Lehn (centre front) at the Mary Martha home.

The women also shared stories about the exotic British food, the bridge parties, ladies “who stayed in their housecoats until noon” and ate dinner at 8:00. They talked about their employers’ beautiful clothes, the boxes of castoffs and the misery of English children who had too many toys. I also heard about the Mennonite women’s superior ways of washing a floor, whitening the laundry and starching a shirt.

Nonetheless, there were embarrassments too – confusion with the English language, telephone rituals, food requests, recipe ingredients and furniture polish. Then there was the silence. Much was said by not saying.

That these young immigrant women were vulnerable and exposed to perilous working conditions is without dispute. The matrons (administrators) of the Girls’ Homes were much more aware of the hazards than the young women. But the purpose of this book is not to decode the euphemisms the women used to mask events, nor is it to divulge secrets. This publication is intended to honour the contributions of these women and to ensure that they are not forgotten.

These Mennonite maids often worked 15 hours a day. But though the work was strenuous, repetitive and often lonely, the young women had an unusual amount of autonomy and sense of self-sufficiency. They spoke of streetcar access to anywhere in the city, Sunday afternoons in rowboats at Lost Lagoon, picnics in Stanley Park, downtown shopping trips on the “maids’ day off.” Most talked about the “good times” they had both in the Girls’ Homes and on their time away from work.

However, there was little talk of good times or fun among their parents, most of whom had just recently (in the 1920s) escaped the terror of the new Communist regime in Russia.

Most families were very poor and owed a debt to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) for their travel to Canada. Everyone who was able worked in beet fields, grain fields, hop yards, processing plants, factories and sawmills.

Yet this labour did not provide the necessary cash to survive while also paying for the family’s travel debt. Desperate parents knew that their daughters could work as maids in nearby cities. Help Wanted ads in Vancouver newspapers confirmed the need for domestic workers. The wages were enticing.

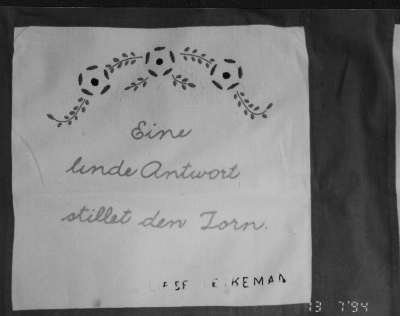

The young Mennonite maids were in vulnerable situations, working in other people’s homes. This needlework by Liese Letkeman says, “A gentle answer stills the storm.”

The choice to send their daughters into the city to work was difficult for most parents, regardless of the location of the city. Freda Brucks Derksen recalls her parents’ anxiety when her older sisters were sent to work in Lethbridge and Calgary. Mennonite families had settled in rural areas and no Girls’ Homes had yet been established in either city in the 1920s or ’30s

Although the significance of these young Mennonite maids’ experiences was not apparent for years, the more recent response to several publications from the general public, from the greater Mennonite community and from the academic community affirmed their importance. The contributions of these women were now viewed through the lenses of a general readership and also the lenses of sociology, anthropology, ethnography and gender studies.

I realized then that the experiences of these ‘girls’ were far more than simple stories. These young women had a considerable effect on the role of Canadian families and women in urban and rural spaces. Women’s domestic work in Vancouver also challenged previous assumptions about migration and settlement patterns held by the Mennonite community and by Canadians in general. Their experiences needed to be recorded in their own voice and examined under new rubrics.

As a result, I became determined to record the struggles and successes of the hundreds of Mennonite women who were associated with the two Girls’ Homes of Vancouver – the Mary Martha Home (General Conference of Mennonites) and the Bethel Home (Mennonite Brethren Conference).

Although Daughters of the City is not an academic publication, I have consulted scholarly research to provide a more comprehensive socio-historical context for the Girls’ Homes. Endnotes and recommendations for further reading are included, and interviewees are listed.

Notably, both the academic community and the Mennonite community have welcomed my previous publications and presentations. In one of my earliest lectures (late 1990s), sponsored by the Mennonite Historical Society of B.C., 300 women attended. We shared ethnic food (Zweiback, Platz, pickles, tea and coffee), we sang a ‘table song’ before the meal and we heard four matrons of the former Girls’ Home talk about their experiences.

Thus, the purpose of this book is twofold: firstly, to preserve the historical account in an accessible form for the Mennonite women and their descendants whose lives were shaped by domestic service in Vancouver; and secondly, to inform a wider audience about the role of these women who arrived in Canada in two waves of immigration (mid-1920s and 1948–50).

The Mädchen of the two Mennonite Girls’ Homes shaped the attitudes, settlement patterns and class distinctions of not only their families, but also of Canadians. They deserve to be remembered.

The Introduction to Daughters in the City (published this summer by Fernwood Press) is reposted by permission. Colleen Kimmett wrote a good article on the book for The Tyee.

Ruth Derksen Siemens is a first-generation Canadian of Russian Mennonite descent who was born in Vancouver and also lived in a traditional Mennonite community in the Fraser Valley. She is an instructor of writing and rhetoric at UBC. Her PhD in the philosophy of language (University of Sheffield) investigates a corpus of 463 letters written from the former Soviet Union by Russian Mennonites. Some of these letters appear in her edited work. Remember Us: Letters from Stalin’s Gulag (1930-37).

Sandra Borger helped Ruth with archival research, data gathering, scanning photos and interviewing some of the women.

My mother was a teenaged Mennonite live-in maid in Vancouver from 1934 until she got married in 1939. Mom was born and raised in Saskatchewan but her family moved to the west coast because of the drought in the prairies.