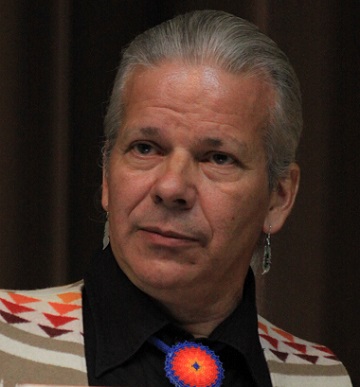

Missions Fest speaker Terry LeBlanc will bring a challenge to “deep-seated Western ethnocentrism in theology and mission.”

Missions Fest Vancouver (January 27 – 29) is upon us, and I’m very much looking forward to hearing many speakers addressing this year’s theme, ‘Justice and the Gospel.’ There is no arena is which that focus is more pressing than our relationship with Indigenous people. In this powerful comment, Terry LeBlanc, one of the keynote speakers, discusses how Indigenous theology is – or should be – changing the way we look at ministry.

When I was a young boy, my grandfather, father and I travelled some distance from our home community to go fishing at a spot known only to my grandfather. Having driven as far as roads would take us, we got out of my grandfather’s old beater and, gathering our gear, set out on the trail toward this favourite fishing spot.

We soon found ourselves in the middle of a deep, dark woods making our way along a narrow trail where, with each passing step, the way ahead and behind became less and less perceptible. On more than a few occasions I expressed my concern to my grandfather; each time he sought to reassure me.

Finally, unable to hold in my anxiety, fearful about what lay ahead of us, even more anxious that the way back would never again be found, I tugged frantically on my grandfather’s arm. “Grandfather, grandfather,” I cried out, “We’ll be lost!”

Sensing the rising fear in me, my grandfather knelt down and, after reassuring me more fully, taught me a lesson – one that has guided my thinking and actions from that day to this.

In the mixture of languages that was his habit of speech, he told me that each new trail we take could seem like it leads along an uncertain path; the way back can seem unclear, obscured by the landscape.

“But,” he said, “When you set out on a new trail, if you spend twice as much of your time looking over your shoulder at where you have come from as you do where you are going; if you fix the landmarks behind you in your mind the way they will appear to you when you turn to take the trail back, you will never become lost – you will always be able to find your way home.”

That day, my grandfather gave me the ability to find my way to and from all of the various destinations in life that would lie before me; all of which, as I set out on each new trail, were initially unknown.

Contemporary societies – not just North American – are no longer used to looking at where they have come from. They are far more fixated on an as yet unknown and unknowable future – on what comes next. Rather than use the past to help determine where they are on the trail of life in relation to where they started, they plunge ahead, frequently blindly, expecting that the future will correct any mistakes they make in navigation.

Mission’s Indigenous impact

For generations, Native North Americans and other Indigenous peoples have lived the false belief that a fulfilled relationship with their Creator through Jesus required rejection of their own culture, and the adoption of another – European in origin.

In consequence, conventional approaches to mission with Indigenous peoples in North America and around the world have produced relatively dismal outcomes. The net result has been to subject Indigenous people to deep-rooted self-doubt at best, self-hatred at worst.

As Isabelle Knockwood, a survivor of a church-run residential school observed:

I thought about how many of my former schoolmates, like Leona, Hilda and Maimie, had died premature deaths. I wondered how many were still alive and how they were doing, how well they were coping, and if they were still carrying the burden of the past on their shoulders like I was.1

Countless efforts, over the past four centuries or more, have been targeted not so much to spiritual transformation as they have been to social and cultural annihilation (many of these spawned in the 20th century alone).

The relatively unambiguous mandate of many mission conferences in the 20th century was, ostensibly, to continue civilizing and Christianizing – a task begun as far back as the earliest mission of the Jesuits at the beginning of the 17th century. Their collective failure to produce the outcomes intended might cause us to conclude that Indigenous people possess a unique spiritual intransigence to the Gospel.

But that would not tell the whole story.

The real tale is best told through a more careful examination of the numbers of Indigenous people who, despite the tragic engagement of Christian mission in their lives and communities over the centuries, still claim affinity to one tradition or another of the Christian church – and of these there are many.

The real tale is best told through a more careful examination of the numbers of Indigenous people who, despite the tragic engagement of Christian mission in their lives and communities over the centuries, still claim affinity to one tradition or another of the Christian church – and of these there are many.

Here we discover people from the Arctic to Mexico, Oceania to Australia, stumbling heavenward within the kingdom of God despite the bleakness of their current social realities – much of which is clearly and unequivocally connected to the wrong-headedness of mission to their people.2

Christianity, as presented to us over the centuries, offered soul salvation, a ticket home to eternity, but had been essentially unconcerned with the rest of our lives – lives that history makes clear, were nonetheless fully exploited by those bringing the salvation offer.

It was in 1999, with this and more in mind, that the renewed controversy over Indigenous cultural and theological contextualization of the gospel compelled our small group of Indigenous Jesus followers to respond. Since that time, our unwavering commitment has been to facilitate transformation and growth through the power of the gospel as over against the propositional, controlling, westernized, religious expression of that gospel often presented to us.

At times this has been a daunting task, since the juggernaut of Western mission, theology, and theological method has tended to decry as heterodox anything of a contrary nature.3

Central to accomplishing our purpose is the challenge of a deep-seated Western ethnocentrism in theology and mission – at least as experienced among our own people.

It is our view that the essentially mono-cultural, mono-philosophical foundations of Christian faith in North America have stultified theological and therefore missiological development for many decades, relegating the practice of faith to variant but nonetheless unhealthy patterns of self-absorbed individualism.

Our response to all of this is visible in several shifts.

Old foundations, new footings

First, we have shifted away from the dualistically framed philosophies within which European and Euro-North American theologies have been classically undertaken, to a more holistic philosophical frame of reference.

Active engagement with traditional Indigenous thinking and a more biblically faithful position toward the gospel has been the result of this shift. To Indigenous people, life is not easily captured in the simple binaries and either/or realities still so comfortably situated within Western thought. The Hebraic “both/and” is much more akin to our philosophy than the Greek “either/or.”

Consider, for example, the continuing Western struggle to understand that the whole of creation is the focus of God’s redemptive activity in Christ.

The Christian scripture is abundantly clear that redemption through Jesus’ work on the cross has implications far beyond our generally limited focus on the restoration of human beings alienated from their Creator.

If the covenant of Genesis 9 were insufficient to make the case, Paul is crystal clear that “the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time.” (Romans 8:22) The context is clear, it awaits its own redemption – a status that has been put on hold, he further notes, as it “waits in eager expectation for the sons [and daughters] of God to be revealed.” (Romans 8:19)

Seldom in evangelical writing does the idea that Jesus came to give his life so that the rest of creation might also be redeemed find a voice.4

Another shift lies in our biblical starting point. Western theology, in the firm grip of Augustine’s articulation of sin and sin’s nature, has inevitably commenced its theological undertakings with the Genesis experience of chapter three, “the fall.”

It is precisely this practice that made it theologically possible for missionaries and monarchs, popes and priests, vicars and viceroys, to proclaim our lack of humanity and soullessness – to pronounce, as did missionaries of the 17th century:

“These heathen must first be civilized so that they might then become fit receptacles of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.”5

Curious that a people who believed in the omnipresence of God could announce his absence from what they deemed to be a godless, heathen land and people!

Compounded dualisms together with this Genesis 3 start, created the European frames of reference whereby Indigenous peoples could be relegated to a state less than human and therefore subjected to a capricious death at the hands of European colonials as per Aquinas’ own thought centuries before . . .

“Unbelievers deserve not only to be separated from the Church, but also . . . to be exterminated from the World by death.” – Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1271.

This and other sentiments exactly like it are what grew (and continue to grow today) from the interlacing of a Genesis 3 starting point with theologies rooted in binary thinking.

Our history as Indigenous people, and our general disposition toward life, suggests that all of creation is of a spiritual nature – not just human beings. We see this clearly expressed in scripture (e.g. Genesis 1:28-30; Job 12:1ff; Romans 8:22ff).

This has implications for how we view the work of Jesus and the cross – not simply as providing for soul salvation, but rather ensuring the restoration of all things to the plan and intent of God. Experience with both the biblical text and life itself tells us that all of creation is possessed of a spiritual nature – and all is the focus of God’s redemptive activity in Jesus.

Christian theology has struggled to comprehend this, assigning the labels pantheism or panentheism to a more inclusive understanding of the nature of the spiritual, which includes the rest of creation as a concomitant focus for Jesus’ work on the cross.

To be sure, human spirituality is augmented, and therefore differentiated from the rest of creation by the gift and impartation of God’s image and likeness – now marred by the collapse of creation’s harmony. But this does not diminish the spiritual nature of the rest of creation, rendering it “inanimate stuff.”

Though there are other shifts we have made, one other that is significant lies in our understanding of story. To us, communal narrative serves a hugely compelling and significant function. It can be both objective and factual, containing clear teachings for life, which, if ignored, put one in dire peril, while simultaneously mythic and broadly flourished for narrative effect – all in an integral collection where one form is not valued above the other.

Each form or genre of story, each teller of a story within the grander narrative of the community, is fitted within the wider collection; a compendium the community stewards through the generations to teach about the world and the way of life within it. Removing one, subjecting one to dissection, or truncating its meaning by casting doubt on its authenticity, when the ancestors have clearly included it, destroys the whole.

As one member of our community has said, “Changing the story of the Three Little Pigs to remove the house of sticks and go directly to the house of bricks is to lose the story. My grandchildren would respond and say, ‘Nookum, that’s not the way the story goes!’”

This means, to most of us who are Christian, that the scriptures must not be dissected by literary method – or even contemporary narrative theological technique – so as to arrive at the “essence of the story” and its teachings or the central story-teller’s words; nor can we assign any new meaning we like according to our own experience; doing so truncates the story, rendering it impotent.

Our hope in making these shifts is to bring change for our people, and others who may wish to come along on the journey – all rooted in the story of the person, work, life, teaching, death and resurrection of Jesus.

1. Knockwood, Isabelle. Out of the Depths: The Experiences of Mi’kmaw Children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. 1992. P. 134.

2. Native North Americans “lead” in all the negative social statistics in Canada and the United States as well as in Mexico: poor health, addictions, family violence, unemployment, homelessness, lack of education etc.; with extremely high representation among First nations, Inuit, Métis and Native American communities.

3. It needs to be said at this point that neither conservative nor classic liberal Christians – particularly in the USA – are significantly different in this expectation. Both, with their respective points of dogma, expect their particular tracks to be followed.

4. I note the very recent work by Howard Snyder and Joel Scandrett, Salvation Means Creation Healed, as a recent change in thinking.

5. Chrestien Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia.

This article is re-posted by permission from the Mission Fest 2017 magazine.

Dr. Terry LeBlanc, a Mi’kmaq-Acadian, is executive director of Indigenous Pathways and also founding chair and director of North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies (NAIITS). He holds an interdisciplinary PhD from Asbury Theological Seminary and is adjunct professor and Indigenous Studies Program Director at Tyndale University College and Seminary in Toronto.

Thank you for such a deep insightful presentation of the great theological gap that has kept the ineffective stance of western theology in reaching our first peoples. May we come to the place that we trust that when the Spirit and the Word are germinated in the spirit of a people it will develop into its organic expression. Lord forgive us for exchanging the Life of the gospel into a theology and then using it in order to subjugate others into our image.