A recent Angus Reid poll shows the Canadian public falls into four broad categories in terms of religious belief.

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat made a plea April 15 “that many of this newspaper’s secular liberal readers should head en masse to church.” The conservative Catholic (who delivered the Laing Lectures at Regent College in 2014) urged them to return in Save the Mainline:

Do it for your political philosophy: More religion would make liberalism more intellectually coherent (the “created” in “created equal” is there for a reason), more politically effective, more rooted in its own history, less of a congerie of suspicious “allies” and more of an actual fraternity.

Do it for your friends and neighbors, town and cities: Thriving congregations have spillover effects that even anti-Trump marches can’t match.

Do it for your family: Church is good for health and happiness, it’s a better place to meet a mate than Tinder, and even its most modernized form is still an ark of memory, a link between the living and the dead.

Many religious Canadians might have had similar thoughts as they perused some recent poll results:

Angus Reid / Faith in Canada 150

A study released April 13 in the National Post is the first installment in a year-long partnership between the Angus Reid Institute and Faith in Canada 150. The headline tells the story: Canadians may be vacating the pews but they are keeping the faith: poll.

Following are the key findings, according to the study:

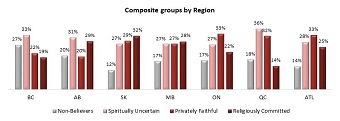

- Four broad segments of this spectrum are analyzed in this survey: The Non-Believers (19% of the total population), the Spiritually Uncertain (30%), the Privately Faithful (30%) and the Religiously Committed (21%)

- Though most Canadians do not rule out personal faith, they are more likely to view the word “religion” negatively (33% do) than positively (25%)

- Higher levels of belief are correlated with higher levels of personal happiness, charitable giving, volunteerism and overall community engagement

The most devout religious followers in Canada are more likely to be found in the prairies. Approximately three-in-ten from Saskatchewan (32%), Alberta (29%) or Manitoba (28%) fit into this end of the spectrum as Religiously Committed. By contrast, 14 percent of Quebec residents and 19 percent of British Columbians can say the same.

For their part, Quebecers are most likely to be found in the middle segments. Two-thirds of Quebecers fit the two middle categories (68%), the largest such grouping in the country. BC is home to the highest proportion of Non-Believers at just over one-quarter (27%) and is second only to Quebec in Spiritual Uncertainty (33%).

• The poll found 45 percent of British Columbians oppose even partly funding private schools, whether they’re religious or not.

• British Columbians were mixed on many spiritual issues, with 42 percent believing “mindfulness meditation should be allowed in public schools.” Just 35 percent opposed the meditative practice which teachers are increasingly teaching their public school students. It is linked most strongly with Buddhist and Hindu spirituality.

• Though the Lord’s Prayer was banned five decades ago from BC public schools, 39 percent of British Columbians believe Christian prayers should be allowed in schools, while roughly the same proportion were opposed.

• A firm two of three British Columbians reject Muslim ceremonies and prayers in public schools. The only group that backed Islamic prayers in schools were BC. Muslims, by a whopping 89 percent margin.

The BC Education Act requires public schools to be “secular” and not favour one religion over another.

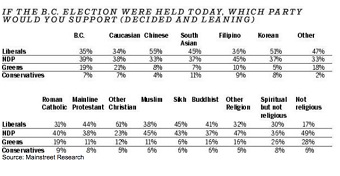

Todd also reported on another Mainstreet Research opinion poll for Postmedia News which reveals the leanings of BC voters based on their religion or lack of it, and ethnicity.

Todd also reported on another Mainstreet Research opinion poll for Postmedia News which reveals the leanings of BC voters based on their religion or lack of it, and ethnicity.Evangelical Christians [who make up most of those in the “other Christian” category] are leaning strongly toward the BC Liberals in the next election.

The large numbers of British Columbians who say they are “not religious” are far more likely to opt for the front-running NDP, with some favouring the Greens.

And Metro Vancouver’s large Sikh population is on track to split its votes between the Liberals and NDP, at the same time as they join other visible minorities in rejecting the Green party. . . .

BC’s Roman Catholics and mainline Protestants, accounting for one in three British Columbians, more or less follow province-wide voting trends.

Go here for the full article.