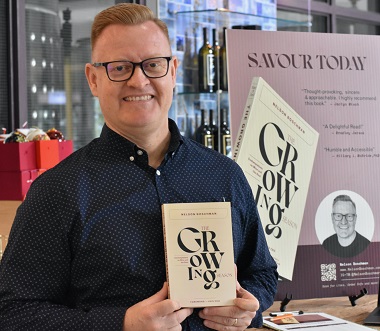

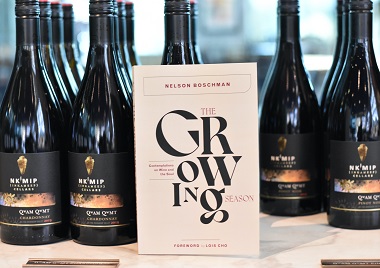

The first launch for ‘The Growing Season’ took place at Nk’Mip Cellars in Osoyoos, where Nelson Boschman was an intern in 2018.

This article is from the Introduction to The Growing Season: Contemplations on Wine and the Soul, by Nelson Boschman.

Who could have been more invested in physical life on earth than Jesus? I’ve been preaching lately on “consider the lilies of the field.” The way he could look around and see anything and make it part of what he was talking about. – Barbara Brown Taylor

By taking a long and thoughtful look at what God has created, people have always been able to see what their eyes as such can’t see . . . – Romans 1:20, The Message

I’ve been searching for a more this-worldly spirituality.

Something not so fixated on questions of where we go when we die.

Something more inclined to explore what it means to live well, to flourish as humans, here and now.

Something a little less pearly gates and a lot more consider the lilies.

I’ve been searching for a good while. I’ve met obstacles and challenges. For one thing, I’m a pastor, and as it turns out, many church folk are fairly focused on the next world.

I’m also a musician and I’ve led musical worship in church for years. One time, I got some feedback I didn’t expect and will never forget.

The vineyards from Nk’Mip Cellars.

The sermon was about an ancient Israelite king acting in a way that was consistent with God’s intent: rebuilding Jerusalem, restoring city walls, looking after the poor.

I wanted our worship that morning to reflect God’s clear concern for the here and now. I felt energized by these physical, earthy, this-world themes. (You know, because of my ongoing search.)

In preparation, I went to the Psalms. In this ancient prayer book, rocks and trees, fowl and fish, streams and stars are all handiwork of the Divine, elements of a world God loves and invites humans to care for.i Because creation matters deeply, we also find poetic prayers about what it means to govern with justice and mercy in the Psalms.ii

For worship that morning, I chose songs that echoed that same language. Songs that were both this-worldly and centred on Scripture. They spoke of God as the God of the broken, the friend of the weak. The God who lifts the needy from the ashes and heals the barren.

In my mind, it was one of the most down-to-earth worship sets I’d ever put together. The congregation seemed super into it. They sang loudly, with lifted hands and hearts ablaze.

As soon as I sat down after the last song, a kind, older woman sitting in the row behind me tapped my shoulder. I turned around. She leaned in close and whispered,

“When you lead worship, you lead us right up to the gates of heaven.”

You have got to be kidding, I thought. I’m putting down city-building and justice and she’s picking up fluffy clouds and cream cheese.

“Thank you,” I said quietly and turned back around.

She meant well. I received it as a compliment. Musical worship ought to give rise to a sense of the transcendent. I’m glad those songs helped that woman feel something Beyond. But at that moment, I cared more about the Immanent.

There’s a healthy tension here, of course. All of it matters. Unseen and seen. Spirit and body. Heaven and earth. But, to me, things seemed out of balance.

The spirituality I’ve been searching for invites me to notice what Jesus noticed. Lilies and sparrows. Sheep and shepherds. Vines and branches. He always seemed to call folks’ attention to the concrete. To the material. To things people can see, in order to evoke a different kind of seeing.

Jesus’ spirituality was next-level earthy. It was also radically inclusive.

In one breath, he’s telling us that God cares about birds. In the next, he’s saying, “God loves humans even more.” People who wrote the earliest accounts of Jesus’ life said he was never without a story.iii He wanted those he encountered to see themselves, to see their own lived experience, in what he said and taught. There was room for everyone in his stories, including those society excluded. And he made it a regular practice to call out anyone who claimed otherwise.iv

Like so many others, I’m becoming more and more captivated by what Jesus embodied most clearly: a spirituality for the rest of us.

I’ve been searching for a more this-worldly spirituality.

I’ve been searching for a more this-worldly spirituality.

And like a gravitational pull, there’s been a growing sense that it’s been searching for me.

In many ways, this book is a chronicling of that search. One that has only intensified over the years. One that led me to spend my sabbatical in more agrarian settings than I usually inhabit.

One that deepened my interest in wine.

Footnotes

i Psalm 8.

ii Psalm 72 is a good example of a prayer that links themes of creation and justice explicitly. I love how verse 3 is rendered in The Message: Let the mountains give exuberant witness; shape the hills with the contours of right living.

iii Matthew 13:34-35; Mark 4:33-34.

iv In several texts within the gospels, Jesus intentionally includes people who could be grouped in categories of last, least, lost, and little. Check out a few here: Matthew 20:16 (last); 25:40 (least); 18:11 (lost); 19:13-14 (little).

Nelson Boschman is a pastor, writer, spiritual director, jazz musician, wine enthusiast, husband and father of one in Vancouver. He is the pastor of spiritual formation at Artisan Church, and a partner of SoulStream, a community that seeks to nurture contemplative experience with Christ, leading to inner freedom and loving service. Follow on Instagram @nelsonboschman.

Congratulations, Nelson! Very exciting stuff. Maybe heaven is right at our finger tips. Thankfully, there seems to be more people exploring this theme lately. Check out Alexander Hampton, assistant professor of religion at U of T and his Dawn Chorus project (interviewed on CBC radio) as he explores the intersection between spirituality, the natural world and music.