This vignette reflecting on Vancouver’s history appeared in the March-April issue of Faith Today.

It was the spring of 1917. Canada had been at war against Germany for nearly three years. Like everyone Canadians had expected a short war, but the end was nowhere in sight. With voluntary recruitment efforts drying up, the government proposed turning to conscription, provoking fierce divisions that lasted for decades.

The year also featured another controversy that does not get nearly as much attention, but had more spiritual importance in the long run – a debate about the future of Protestantism.

On one side were those who believed Christianity needed to change its beliefs and priorities to keep up with the times. Often called liberals or modernists, they believed modern scholarship had disproved the reliability of the Bible and were skeptical of traditional doctrines. Instead, they argued the Church’s priority should be “social regeneration” through support for political causes like the prohibition of alcohol, women’s suffrage and urban planning reform.

On the other side were more conservative Protestants, later often called Evangelicals, who continued to defend the reliability of the Bible and traditional doctrines. Some were called “fundamentalists” for their outspoken defence of the fundamentals of the faith. Although many of them also supported social reform, they saw the Church’s primary task as “soul winning” – preaching the gospel.

In Canada at the time of the First World War, this tension was largely hidden below the surface. In most of the large Protestant denominations, liberalism was gradually winning over the theological colleges, head offices and eventually most of the pulpits, but few made a public issue of this.

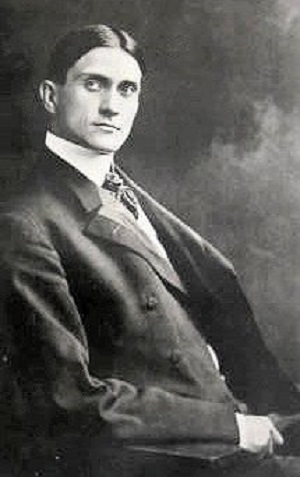

Vancouver was one of the big exceptions. As historian Bob Burkinshaw explains, the tension burst out into the open. The catalyst was Dr. French E. Oliver, a Presbyterian preacher from the Bible Institute of Los Angeles. A group of Vancouver’s evangelical professionals, businessmen and ministers from a range of denominations – Anglican, Baptist, Methodist, Plymouth Brethren and Presbyterian – invited him to come lead a six-week evangelistic campaign in May and June 1917.

Oliver preached to crowds of thousands in a purpose-built ‘tabernacle’ near the downtown. Mostly he preached a straightforward message of sin and salvation, and nearly 2,000 people gave their lives to Christ during the campaign.

But he also preached directly against the influence of liberalism, which he identified as a major threat to the gospel and the Church. He told the crowds he would not “use a feather duster” when it came to something as important as “the defence of the faith.”

The more liberal ministers in the city responded from their pulpits and in the press that Oliver was closed-minded and stuck in the past. Some even accused him of being in the pocket of business interests who wanted to prevent social reforms (Burkinshaw concludes there is no evidence of this).

Perhaps their most effective charge was that Oliver was creating unnecessary controversy and driving a wedge between the churches of the city.

The Christians in Vancouver were indeed split over Oliver’s visit. In fact, the controversy served to convince many Evangelicals the mainline denominations were indeed too liberal. Afterward they began to build independent evangelical institutions outside mainline control.

So were the critics right? Did Oliver cause division in a time when unity was needed?

There is no question he was a divisive force, and controversies can be ugly. This one had ugliness on both sides, especially when they accused each other of being pro-German, an inflammatory charge in 1917.

Oliver exposed the deep divide that already existed – between Protestants who believed in the full trustworthiness and authority of the Bible and those who did not, and between those who saw the Church’s primary purpose as soul winning and those who saw it as social regeneration.

It took decades, but those fault lines also eventually surfaced in the rest of the country. In the meantime, the voices calling for unity also ensured liberalism established a firm hold on the big denominations. By the time the divisions became painfully obvious in the 1960s, most Evangelicals had few options besides walking out.

Yes, controversy can be ugly, and division is not something to strive for. Yet sometimes controversies reveal hidden truths, and sometimes the price of unity is too high to pay.

Kevin Flatt is associate professor of history and director of research at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario. Read more in the series at www.FaithToday.ca/HistoryLesson.

This article is re-posted by permission.

While looking for information about French E. Oliver, I came across an impressive local site that I’d never seen before – Vancouver as it Was: A Photo-Historical Journey. One entry called A Tent for French has a picture of the Evangelistic Tabernacle which housed Oliver’s meetings and another of the sponsors of the event and construction workers.

This address by French on The Signs of the Times gives a sense of the controversial nature of his theology.