Three years ago this month, 70,000 Vancouverites took to the streets in the Walk for Reconciliation, committing to a new relationship between settlers and Indigenous peoples. Coming up soon (October 14 – 15), Walking from Wrongs to Rights will help the church take another step in that journey.

Three years ago this month, 70,000 Vancouverites took to the streets in the Walk for Reconciliation, committing to a new relationship between settlers and Indigenous peoples. Coming up soon (October 14 – 15), Walking from Wrongs to Rights will help the church take another step in that journey.

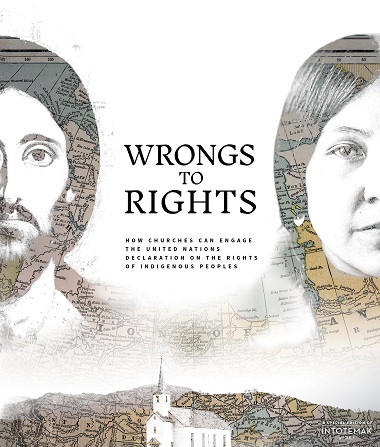

Presumably the conference is named after – or in sympathy with – a recent collection of writings: Wrongs to Rights: How Churches Can Engage the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Local pastor Laurel Dykstra wrote one entry, ‘Declaration and Action: Indigenous Communities and Relationship to Land.’ This comment is posted by permission.

A couple of weeks ago, members of our community joined a circle of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in our diocese to respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action and were struck by the heavy reliance that these calls have on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The circle was made up of people who have been involved in the slow work of church-Indigenous relationship building before and after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, mostly from a justice perspective. Some are very grassroots, some have an abundance of credentials and degrees, but the only one in that gathering who had actually read the full text of the Declaration was a university student in an Indigenous Feminisms class.

So the questions, for me and my community – and more broadly for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Christians who are seeking to address issues of global climate change and ecological injustice – are these: How important is the Declaration? What does it contain? How do we begin to engage with it?

I am not an expert. I am a person for whom a confluence of factors – the biblical mandate for justice, a knowledge and love for the plants and creatures of these Coast Salish territories, the powerful witness of Indigenous land defenders, residential school survivors, cultural practitioners and historians, activists and elders – call me to stumbling and imperfect action for climate justice.

I write to those who share that constellation of concerns and vocations out of a profound urgency. Around the world, Indigenous communities, northern communities, coastal communities are dying because their land and water are poisoned and leaders are silenced (even killed) when they speak out or organize community defence.

What I have to offer is a brief tutorial on the Declaration and some observations as to what it might mean for Christians concerned with environmental justice.

First a quick and dirty look at the Declaration from an environmental justice perspective. Nearly half the Declaration pertains to the relationships of Indigenous people to land. The preamble to the document emphasizes colonization and removal from land; the right to land, territories, resources; the threat and opportunity of land development; and the militarization of Indigenous land.

After the “rights of indigenous people,” the third most used word in the content of the Declaration is “land,” the second is “develop” and the fifth is “territory.” Nine articles refer explicitly to Indigenous peoples’ rights and relationships to their land; one article is concerned with treaties. A further eight seemingly less controversial articles – like the rights to practice traditional sciences, medicines and education, retain place names, access sacred sites, maintain cross-border relationships and even speak Indigenous languages all involve relationship to and control over land.

In terms of environmental justice, the most important parts of the Declaration are Articles 29, “the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources,” and Article 32, “the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources,” which includes the key phrase “free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources.”

So what might this all mean for Christians who are concerned about environmental justice?

First of all, not everybody has the inclination or capacity to read a 16-page, 42-article, legal-language, international body-generated, rights-based document that, unlike international trade agreements, is nonbinding. Nor do they need to.

To give just a few examples, many Indigenous clergy in my denomination serve isolated and geographically dispersed communities facing poverty, addictions, suicide and unemployment. While these issues have their roots in displacement from land, a UN Declaration is far from addressing their practical and immediate needs.

Some Indigenous and land-defender communities believe the Declaration is a European, rights-based model at odds with their understanding of relationship and responsibility to their traditional territories. Moreover, Indigenous peoples are actively practicing the principles recognized by the Declaration and have been for centuries, not based on the external authority of an international document but on the lived experience and authority of Indigenous culture in relationship to land.

So the Declaration is not everything, but it is important in a number of ways. Whether you read it or not, it is useful to know that the document exists, that it is profoundly concerned with land, and that many Indigenous peoples helped create it and are hopeful that persistently leveraging its growing legal authority will result in real change for their communities.

The emphasis on land makes it clear that it is not possible to meaningfully engage with issues of environment, creation or the earth without relationships with Indigenous people. Yet some of us Christians and environmentalists persist in operating from a kind of residual Terra Nullis understanding of “the environment” as empty land.

This, combined with the Church’s role in displacing Indigenous peoples from land through “industrial” residential schools, promotion of farming and outlawing of traditional ceremonies (like the Potlatch), means that we have a great deal of work to do to become trusted conversation partners, much less collaborators in action.

The Declaration affirms Indigenous peoples’ rights to “free, prior and informed consent” to whatever happens to them and on their land seven times. The Canadian government has refused to acknowledge this right. Anglican Indigenous Bishop Mark Macdonald has suggested that supporting Indigenous communities, while corporations and governments try to short-cut their right to free, prior and informed consent, might be one of the most critical opportunities churches have to take action for reconciliation.

It is possible for churches and faith communities to build relationships and take action that supports Indigenous communities in their land and environmental struggles without reference to the Declaration. God’s kingdom of justice and mercy will not come when a critical mass of Declaration study groups have met.

We need to combine our study of this document with learning from Indigenous people where we live what their land issues are. We can follow the leadership of communities, peoples and clans actively practicing their relationship to the land. When we plan solidarity actions, we can follow local protocols for letting First Nations know about our actions on their territory.

We can support them financially, practically.

• At the request of Haudenosaunee organizers, Christian Peacemaker Teams witnessed and documented anti-hunt protesters’ attempts to impede hunters Treaty rights to hunt deer in Short Hills Provincial Park.

• Streams of Justice and Grandview Baptist Church in Vancouver hosted fundraising and education events in support of the Unist’ot’en encampment on traditional lands in the pathway of several pipeline projects.

Christians need to balance being bold for justice with being humble in the face of Indigenous knowledge experience; the situation is so dire and our shared history is so fraught, that over-stepping, disagreements and painful miscommunication are inevitable. But slowly, incrementally, some within churches are growing the relationships and the skills for something that might look like reconciliation in action.

Laurel Dykstra is the priest of Salal and Cedar, a community in the lower Fraser/Salish Sea watershed whose mission is to grow Christians’ capacity to work for environmental justice. In the language of the global Anglican communion, what we do is “strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth.”

Another good (though unrelated) initiative is the TRC Reading Challenge. Its sponsor, Jennifer Manuel, says: “Join us. Take the pledge to read the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report. There’s no deadline. It’s not a race. It’s a commitment.”

[…] Please click on: Wrongs To Rights […]