Several recent books explore the ways in which Christianity has been considered a foreign religion in China.

“If you had no other choice but to stick to China’s state media – and, given censorship, that is the case for quite a few people on the mainland – you might believe that protests in Hong Kong are entirely staged by hostile foreign forces bent on destabilizing the government.” (Michele Penna: China media blame foreign meddling for Hong Kong protests, Asian Correspondent)

The ongoing demonstrations in Hong Kong are a complex phenomenon, but two recurrent themes stand out for me. As Michele Penna points out, the Chinese government fears, and exploits the fears, of threats posed by external forces.

And many commentators, as in the widely-cited

Wall Street Journal article

Hong Kong Democracy Protests Carry a Christian Mission for Some, highlight the significant role of Christians in the demonstrations: “The protests now roiling Hong Kong are about democracy. But there is an undercurrent of another, much older tension: Between Christianity and Communist China.”

Antagonism to foreign intervention is deeply woven into modern Chinese history, and that animosity has often been directed against Christianity.

It is true, after all, that Christian missionaries arrived at the same time as onerous conditions were being imposed on China by colonial powers. While European ships full of opium were arriving at Chinese ports in the mid-1800s, the numbers of converts to Christianity were increasing.

Penna puts it this way:

The fear that foreigners are bent on damaging the country dates back to the Opium Wars [1839 – 1842 and 1856 – 1860], and has developed through years of vexations – the age which, to use a common phrase in Chinese rhetoric, is deemed the ‘century of humiliation.’ “Nationalism born of humiliation,”

says Orville Schell, one of America’s foremost experts on China, is “like genetic material you can’t get off the genome. It keeps re-expressing itself.”

Several recent books touch on these themes, from various points of view.

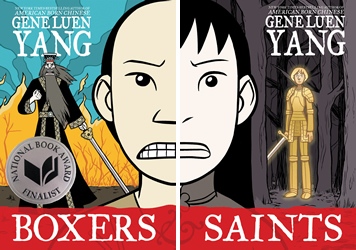

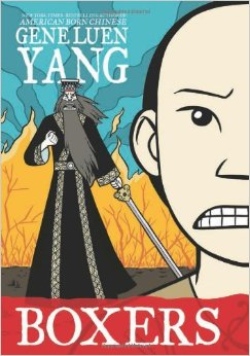

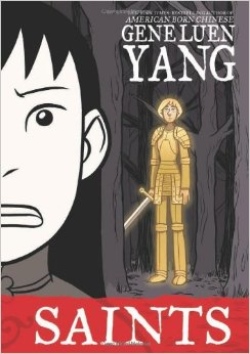

Boxers & Saints

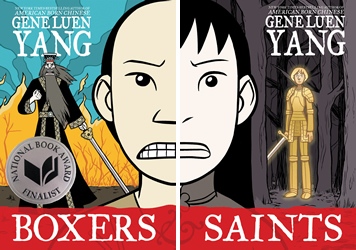

By far the most accessible of these works is

Boxers & Saints, a two-book boxed set which came out last fall. Though these books are a very easy read, they open up a world little known to most of us.

Here is how the author, Gene Luen Yang, describes the project:

The Boxer Rebellion was fought on Chinese soil over 100 years ago. Back then, the Chinese government was incredibly weak. Western powers were able to establish concessions – pieces of land that functioned as colonies – all across China.

The poor, hungry, illiterate teenagers living in the Chinese countryside felt embarrassed by their nation’s weakness, so they came up with this ritual that they believed would give them mystical powers. Armed with these powers, they marched across their homeland into the major cities, killing European missionaries, merchants, soldiers and Chinese Christians. Because their martial arts reminded the Europeans of boxing, they became known as the Boxers.

Boxers & Saints is a two-volume project. In the first volume, the Boxers are the protagonists. In second, their Chinese Christian enemies are.

I wanted each volume to be distinct from the other. Boxers is much longer, almost twice as long as Saints. It’s my attempt at a comics version of a Chinese war epic, full of glory and color and bloody battle sequences.

Saints is shorter, more intimate, more humble. The scope of the story is more limited, as is the color palette. I pulled from the aesthetics of American autobiographical comics, and I hope it reads like a personal journal.

Graphic novels aren’t really my thing, and it goes without saying that

Boxers & Saints does not provide much historical context. But I found the story and the images quite moving; bolstered by further reading, the books offer some real insights into the depth of anti-foreign feeling which has been so significant a reality over the past 150 years or so.

Probably most appealing aspect of the books is the degree of balance Yang brings to his work. As a Chinese-Catholic-American, he clearly feels empathy for all his characters. In a long and interesting

interview in

School Library Journal, he said:

I first became interested in the Boxer Rebellion in 2000, when Pope John Paul II canonized 120 Chinese Catholic saints. My home church was incredibly excited about this. We had all sorts of celebrations and special masses.

When I looked into the lives of these saints, I discovered that many of them had been martyred during the Boxer Rebellion. The more I read about the Boxer Rebellion, the more conflicted I felt. Did I sympathize more with the Boxers or their Chinese Christian victims? That’s why the project ended up as two volumes. The protagonists in one are the antagonists in the other.

Some might disdain the graphic novel approach to major historical issues; I recommend giving it a try.

The Missionary’s Curse

In his

New York Review of Books article, Ian Johnson says: “

The Missionary’s Curse is a rich piece of microhistory, replete with violent priests who bullied their flocks and pious missionaries who spent their lives in hiding. But the tale is even more ambitious than the recreation of this bygone era, with Harrison using it to challenge contemporary ideas about how foreign ideas are absorbed in China.”

Harrison compares the way in which the Chinese state views the relationship between foreign powers (religions) and China, and the way in which the Catholics of Cave Gulley village see the situation. Here, in her words, is the mainstream Chinese view:

The current version of this history is shaped by the Chinese Communist Party, but it has its origins in the perceptions of Qing dynasty officials in the 1860s, who thought that the Catholic villages they saw around them were made up of people converted by the missionaries who had entered China since the Opium War. The missionaries themselves encouraged this idea, and the communal violence of the 1900 Boxer Uprising made it part of popular culture.

Then in the early 20th century it was absorbed into the story of a great national struggle against foreign imperialism, which was later inherited by the Chinese Communist Party. In this story of heroic struggle, Christians found themselves placed on the side of the villains. . . . Today, Catholics [and other Christians] are no longer under pressure to renounce their religion . . . but this version of history remains pervasive in textbooks and newspapers, on the television and in the minds of those they meet whenever they go beyond the village.

On the other hand, according to Harrison, “The Shanxi Catholics’ own version of their history is very different.” They remember ancestors who converted to Catholicism in the 18th century, and are proud that their own representatives went to Rome to protest missionary domination of the Chinese church. Their communities were massacred by the Boxers in 1900, and faithful believers resisted heroically during sustained persecution during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s.

Harrison challenges the pervasive understanding, through much of the 20th century, that it is not possible to be both Chinese and Christian, that “Christianity can only be successful and authentic as it gradually adapts to local culture.” She responds:

This book has argued, against this framework, that we should instead understand the history of Christianity in China as one in which Christians have over the centuries come to relate increasingly to the church as a global institution.

Johnson says: “Her book is especially timely because the new government under Xi Jinping [president of China and general secretary of the Communist Party] is in the midst of trying to define what is China’s ‘dream’ – what are Chinese values after a century of absorbing so much from the outside world?”

Although Johnson wrote this before the Hong Kong demonstrations, it is hard not to apply his words – and Harrison’s – to the current scene. He adds this comment:

Harrison argues for a broader view of Chinese people’s hopes and aspirations. She acknowledges that China has borrowed liberally from other cultures – her book, after all, is about a Catholic village – but writes that Christian ideas have not been Sinicized as much as many imagine.

On the contrary, the first foreign conceptions that were adopted were the ones most acceptable to Chinese, and over time people strove to add foreign content, not subtract it. Thus ideas in China have tended more toward international norms, not Chinese versions of them.

The trend is slow – frustratingly so for many who argue that China over the past decade has moved further away from international standards, especially in the field of human rights, or even economic regulation. But Harrison has a long view. . . . deep familiarity with China allows her to see connections between her specific narrative and the bigger thread of how China has been confronted with the outside world for the past two centuries.

More than most other books I’ve read on China in recent years, it’s one that rings true, and reinforces the long-term optimist’s view against Chinese exceptionalism, and for a country bound to international institutions and norms.

The Missionary’s Curse is a scholarly work, but it is well written and interesting, not beyond the reach of the average reader with an interest in China.

Some related books

There are an increasing number of books looking at the ways in which the Christian church has become increasingly indigenous while at the same time retaining marks of its international roots.

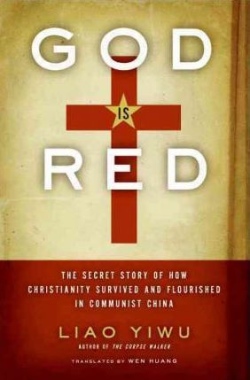

One of my favourite books about China is God is Red. Go here for my review, but this will give you a taste:

One of my favourite books about China is God is Red. Go here for my review, but this will give you a taste:

Local people told [Liao Yiwu, the author] that the China Inland Mission had sent missionaries to Shanghai 150 years ago, and that they had quickly travelled to the furthest corners of China. “These foreigners, ‘with blond hair and big noses,’ [arrived] . . . just in time to save the people from a bubonic epidemic.” Liao, who had grown up in an era when missionaries were portrayed as ‘evil agents of the imperialists,’ was surprised by such stories.

“Three or four generations later,” Liao said, “Christianity was part of the heritage of each individual family and an integral part of local history . . . in the Yi and Miao villages, Christianity is now as indigenous as qiaoba, a special Yi buckwheat cake.”

But at a great price. “The circuitous mountain path in Yunnan province is red because over many years it has been soaked in blood.” His appreciation of the missionaries and his interviews with old pastors, nuns and lay people, in which their long-suffering hope for the future is so apparent, lie at the heart of this moving book.

(Speaking of China Inland Mission – now

OMF International – 2015 is their 150th anniversary. When its missionaries first arrived in China, there was minimal Christian presence; now there are between 50 and 100 million believers.)

China’s Saints by Anthony Clark covers some of the same ground as

The Missionary’s Curse, but on a much broader scale. The subtitle, ‘Catholic martyrdom during the Qing (1644 – 1911)’ tells the story. “While previous works on the history of Christianity in China have largely centred on the scientific and philosophical areas of Catholic missions in the Middle Kingdom,

China’s Saints recounts the history of Chinese martyrdom, precipitated as it was by cultural antagonisms and misunderstanding.”

Two recent books about prominent Canadian diplomat and politician Chester Ronning provide a glimpse through one missionary family into the very foreign yet captivating world of China from the late 1800s through to the mid-1900s.

The Remarkable Chester Ronning: Proud Son of China, by Brian Evans, and

China Mission, written by Ronning’s daughter Audrey, both tell a fascinating story.

China Mission features a rather exciting chapter called ‘Escaping the Boxers.’ Warned by an urgent telegram from Lutheran mission headquarters in Minneapolis in the fall of 1899 to leave immediately, the Ronning family was unable to find transportation right away.

One day they found this warning tacked on their gate:

The foreign devils disturb the Middle Kingdom urging the people to join their religion, to turn their backs on Heaven, to venerate not the gods, and forget the ancestors. Foreign men violate human obligations, women commit adultery. Foreign devils are not produced by mankind. If you doubt this, look at them carefully. The eyes of all foreign devils are blueish.

Eventually, a runner warned them: “You must fly tonight! The Iron Fists have sworn to kill you tomorrow.” Donning black clothes, they headed for the waterfront and boarded a river junk. Before they could cast off, a band of Boxers ran towards the junk, shouting, “Kill the long hairy ones.”

The Boxers swarmed aboard, and a pitched battle ensued. The family would likely have died right there – as did some 250 missionaries and their families throughout China during the Boxer Uprising – except for a dramatic incident of self-sacrifice.

Halvor Ronning, Chester’s father, knocked one of the Boxers into the river as they fought – then jumped in to save him. A fellow missionary – fortuitously a doctor – then saved the man’s life by performing artificial respiration. After an agonizing wait, the Boxer revived, and there was enough of a lull in the fighting for them to cast off.

In his book, Brian Evans reports that “As he approached his teens, Chester sympathized with these anti-government and anti-foreign feelings. . . . [he] later concluded that the Chinese were not actually anti-Christian but against the privileges given to foreigners that the missionaries also enjoyed.”

**************

Whatever happens in Hong Kong, and whatever the role of Christians is determined to be in those protests, deep-seated perceptions about foreign influences and foreign religions will no doubt persist.

I can’t help but think that it’s time to take a fresh look at Christianity and its catalyzing effect on political transformations around the world. Most people in Hong Kong aren’t Christians – so what is it about this particular faith that seems to predispose its adherents to activism? Surely that’s worth examining.

The churches of China will continue to grow and exert greater influence upon all levels of society. This will cause social tension, not only with the [Chinese Communist Party], but also with other religious and ideological groups. Thus, Christians should be attentive to social backlash, especially if the church appears to be triumphalist and dismissive of other Chinese religions, ideologies, traditions and sensitivities.

Earlier optimism about an open hand toward Christianity during President Xi’s term does not appear likely to be borne out any time soon. Preferential treatment will be given toward Buddhism and Chinese traditional religions. The surge of nationalism and the growing perception of ‘infiltrating forces’ from the West will likely increase restrictions on the church in the near future.

However, one would assume that more moderate policies will prevail over time:

- The presence of Christians in the highest circles of society means that even leading CCP officials have Christian acquaintances, Christians working for them or even family members who are either secretly or openly Christians.

- Once faith becomes personal it gets harder to move against it. In China, if it comes to a choice between fidelity to Party and fidelity to family, family usually wins out, and it is unlikely that even the most zealous party members would sacrifice family members upon ideological altars.

The Lausanne authors urge Chinese Christians to be reflective and self-critical. “Triumphalism that seeks to proffer Christianity through appeals to grand buildings and accumulation of power, wealth and influence rather than humility and the cross will ultimately fail.”

Related

By far the most accessible of these works is Boxers & Saints, a two-book boxed set which came out last fall. Though these books are a very easy read, they open up a world little known to most of us.

By far the most accessible of these works is Boxers & Saints, a two-book boxed set which came out last fall. Though these books are a very easy read, they open up a world little known to most of us. Graphic novels aren’t really my thing, and it goes without saying that Boxers & Saints does not provide much historical context. But I found the story and the images quite moving; bolstered by further reading, the books offer some real insights into the depth of anti-foreign feeling which has been so significant a reality over the past 150 years or so.

Graphic novels aren’t really my thing, and it goes without saying that Boxers & Saints does not provide much historical context. But I found the story and the images quite moving; bolstered by further reading, the books offer some real insights into the depth of anti-foreign feeling which has been so significant a reality over the past 150 years or so. The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village, by Oxford University professor Henrietta Harrison, is a fascinating book. It focuses on one Chinese village that has been Catholic since the 1700s – but has broad implications for the way in which we view Western and Christian interactions with China.

The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village, by Oxford University professor Henrietta Harrison, is a fascinating book. It focuses on one Chinese village that has been Catholic since the 1700s – but has broad implications for the way in which we view Western and Christian interactions with China. One of my favourite books about China is God is Red. Go here for my review, but this will give you a taste:

One of my favourite books about China is God is Red. Go here for my review, but this will give you a taste: Two recent books about prominent Canadian diplomat and politician Chester Ronning provide a glimpse through one missionary family into the very foreign yet captivating world of China from the late 1800s through to the mid-1900s. The Remarkable Chester Ronning: Proud Son of China, by Brian Evans, and China Mission, written by Ronning’s daughter Audrey, both tell a fascinating story.

Two recent books about prominent Canadian diplomat and politician Chester Ronning provide a glimpse through one missionary family into the very foreign yet captivating world of China from the late 1800s through to the mid-1900s. The Remarkable Chester Ronning: Proud Son of China, by Brian Evans, and China Mission, written by Ronning’s daughter Audrey, both tell a fascinating story. Eventually, a runner warned them: “You must fly tonight! The Iron Fists have sworn to kill you tomorrow.” Donning black clothes, they headed for the waterfront and boarded a river junk. Before they could cast off, a band of Boxers ran towards the junk, shouting, “Kill the long hairy ones.”

Eventually, a runner warned them: “You must fly tonight! The Iron Fists have sworn to kill you tomorrow.” Donning black clothes, they headed for the waterfront and boarded a river junk. Before they could cast off, a band of Boxers ran towards the junk, shouting, “Kill the long hairy ones.”