James Packer has had a major influence on generations of evangelicals Christians.

This profile is from the Faith in Canada 150 Thread of 1000 Stories. Faith in Canada 150 exists to celebrate the role of faith in our life together during Canada’s anniversary celebrations in 2017.

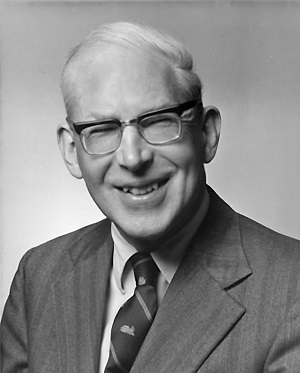

The life story of James Innell Packer is the story of a shy, introverted young boy of humble beginnings who became a dominant voice guiding the development of British and North American evangelical Christianity after World War II.

Such was his influence that in his 1997 biography of Packer Alister McGrath could write, “An entirely appropriate subtitle for this work might have been ‘James I. Packer and the Shaping of Modern Evangelicalism.’”1 This stream of Christianity emphasizes the centrality of the Bible and spiritual rebirth in Christian experience.

Packer’s prodigious influence and leadership in the evangelical world began early. In the face of periodic opposition and criticism – some of it severe and wounding – and being alienated by segments of evangelicalism whose views diverged from his on controversial issues, he charted a straight, sometimes painful, course through the theological currents of the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st.

He has remained faithful to and consistent in his convictions and theological positions, and their application to the Christian life and the ministry of the church. In so doing he has emerged as one of the giants of the evangelical world, whose influence will continue for years to come.

Packer’s inauspicious beginnings belie the prominent and influential leader he would become. Born July 22, 1926, in the village of Twyning, near Gloucester, southwest England, where his father worked as a clerk for the Great Western Railway, he began life as a shy, socially awkward, introverted boy in this working class family.

Upon entering school in 1933 he was bullied, and on a fateful day at the beginning of the first term, another boy chased him into the path of a passing bread van, which struck him, throwing him to the ground. He sustained a major head injury that sent him to hospital, where he underwent surgery to remove bone fragments and repair the damage as much as possible. It left him with a hole in his head, over which he wore a metal plate until he entered college. The scar has remained.

This event, with its six-month convalescence away from school, led to his immersing himself in books, and gaining a new love of reading. The whole experience became one of his defining moments, setting him on a track of reading, study and scholarly accomplishment. His parents’ gift of a typewriter on his 11th birthday provided him with a tool he would use throughout his lifelong writing career.

As a child, Packer attended church along with his parents, and at age 14 went through confirmation. At this stage his Christian faith was nominal. He had never heard anything about conversion.

He began to read the Bible and to think through matters relating to the Christian faith. His coming in contact with the writings of C.S. Lewis sparked his thinking further and “. . . reinforced his growing interest in the truth of Christianity.”2

When Packer arrived at Oxford in 1944, he came in contact with the Christian Union. It proved critical, for at an evening lecture on Sunday, October 22, 1944, Packer suddenly had a vision of being on the outside looking in. He immediately recognized what he had to do. He had to “come in.” So at the invitation he responded, and at that moment experienced Christian conversion.

Six weeks later, at a Sunday evening Bible study, Packer came to a stark realization about the nature of the Bible. “At the beginning of the meeting, Packer was a gentle skeptic; at its end, he was convinced that the Bible was the Word of God. Something had happened to bring him to a conscious realization that Scripture was not human instruction for wisdom about God, but was in fact God’s own instruction about himself.”3 He had experienced what Calvin called “the inward witness of the Holy Spirit” revealing the truth to him.

A final note of significance – while Packer did attend an Anglican church in Oxford, he also came in contact with the Plymouth Brethren, a group Wikipedia describes as “a conservative, low church, nonconformist, Evangelical Christian movement whose history can be traced to Dublin, Ireland, in the late 1820s, originating from Anglicanism.”4

For two years Packer attended many of their Sunday evening meetings. It was here that he became personally acquainted with James Houston, who years later would be the catalyst in Packer’s move to Canada, taking up a position at Regent College, Vancouver.

Packer’s time as a student at Oxford (1944–48) began to lay the foundation for his career. He became a classical scholar, achieving first class honours. “The rigorous linguistic, philosophical and historical training which Packer would receive during his time at Oxford is widely regarded as being reflected in his ability, shown in many of his books, to handle complex arguments with ease and clarity.”5

Here he also decided to pursue ordination in the Church of England, a process completed on December 21, 1952, when he was ordained a deacon, and on December 20, 1953, when he was ordained a priest.

At Oxford he became influenced by the writings of George Whitfield and, most important of all, he discovered the Puritans, notably John Owen and Richard Baxter. Baxter would become the focus of his doctoral thesis in 1952 – the topic: The Redemption and Restoration of Man in the Thought of Richard Baxter.

Here he found a robust theology of salvation and sanctification (bringing one’s life more and more into line with the teachings of Christ). He also found personal help for his own spiritual struggles, and a touchstone for his future theological thinking. The essence of Puritanism is not the public caricature often imposed upon them, but a lively, sincere, and devoted spirituality based on the Bible’s teachings translated into one’s personal life.

During his year at Oak Hill College (1948–49), Packer discovered he could teach. He became convinced that British evangelicalism needed a more robust, scholarly defense, and he saw the possibility of providing that in a teaching career.

Then at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford (1949–52), he took his theological education, eventually graduating with his Doctor of Philosophy degree.

Packer proved during his education years to be a top-rated scholar, impressing both his professors and fellow students. He had become a Puritan scholar, and with his friend O. Raymond Johnston, helped establish the Puritan Conferences, the first of which took place on December 19 and 20, 1950. He and Johnston had invited Dr. Martin Lloyd-Jones to join them and to lead the conferences.

“The importance of these Conferences is clear. A rising generation of theological students and younger ministers were being offered a powerful and persuasive vision of the Christian life, in which theology, biblical exposition, spirituality and preaching were shown to be mutually indispensable and interrelated. . . . It was a powerful antidote to the anti-intellectualism which had been rampant within British evangelical circles in the immediate post-war period . . . the Conference acted as the nucleus of a new and emerging constituency within British evangelicalism.”6

James Packer moved to Regent College after serving in several roles in England.

Leaving Wycliffe Hall, Packer spent the next two years as curate at St. John’s Harborne in Birmingham. There he got valuable experience in pastoral ministry and proved that he could communicate theological truth to ordinary, thinking lay people.

While there he completed his doctoral thesis and even had time for romance. He became engaged to Kit Mullett, a young nurse he had met at a conference in 1952 where he was the main speaker. He became convinced that he should marry and that Kit was the right woman. They married on July 17, 1954.

Kit was the exact opposite of Packer. Wendy Zoba describes her as someone “. . . who possessed all those qualities that [Packer], in his bookish way, seemed to lack. She was practical, relational, lively and independent.” Biographer Leland Ryken adds, “Kit feels comfortable in challenging Packer’s ideas and debating them.”7

The Packers adopted three children – Ruth, Naomi and Martin.

Packer’s time as lecturer at Tyndale Hall, Bristol (1955–61) raised his profile as a teacher and theologian. Here also he became embroiled in his first major controversy – one of many – in his attack on the Keswick teaching on sanctification. His article in the Evangelical Quarterly in 1955 created a firestorm that nearly cost him his teaching position.

His next major foray came in his blockbuster book, Fundamentalism and the Word of God (1958). This book, which to this day has never gone out of print, constituted an evangelical response to Bishop Michael Ramsey’s article, The Menace of Fundamentalism.

This book would “. . . transform the general perception of Packer within evangelicalism, and . . . significantly extend his influence and enhance his reputation.”8 Suddenly British evangelicalism had a new champion.

His second book, Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God (1961), became one of his most influential and widely read books.

Packer’s role in creating a vision, along with colleagues John Wenham and Richard Coates, for an evangelical research institute at Oxford, led to the establishment of Latimer House, Oxford, in 1961. Latimer House became “. . . the leading evangelical think tank and resource centre for evangelicals within the Anglican Church,”9

Packer became the warden, placing him in a unique position of leadership and influence for the next decade (1961–70). Packer sought “. . . to recall the church to its theological and historical roots in the English reformers of the 16th century . . . and subsequently the Puritan writers of the 17th.”10

While there he tackled the radical theology of the 1960s when he published a response to Bishop John A. T. Robinson’s book Honest to God. Packer’s 20-page pamphlet, Keep Yourself from Idols, characterized Robinson’s book as “a plateful of mashed up Tillich fried in Bultmann and garnished with Bonhoeffer.”11

He also became a leading figure in opposing a 1963 proposal to unite the Anglican and Methodist churches, a plan that eventually failed.

Back at Tyndale Hall, Bristol Packer served as principal (1970–72). He totally reorganized Tyndale’s governance structure to resemble the theological institutions he had become familiar with in North America. He also gave “. . . new direction to theological education . . .”12 And he put in place a stellar faculty. “Packer would prove to be a reforming principal . . . .”13

The Anglican Church, however, put all this in jeopardy when it decided to close some of its theological colleges and amalgamate others. A long and convoluted battle ensued, with Packer in the middle of it.

The Anglican Church, however, put all this in jeopardy when it decided to close some of its theological colleges and amalgamate others. A long and convoluted battle ensued, with Packer in the middle of it.

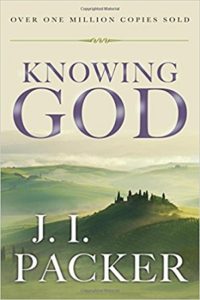

What eventually emerged on January 1, 1972, was a new theological training institution – Trinity College, Bristol. Packer became associate principal (1972–79). He now had time to write, and it was there he wrote the book that made him a household name among evangelicals the world over – Knowing God (1973). By 1992 it had sold a million copies.

Packer also led in the inerrancy debate – the Battle for the Bible. In 1997 he became a founding member of the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, and a key player.

Toward the end of his time at Trinity, Packer found himself in situations that tended to isolate him from mainstream developments in Anglicanism, not the least of which were revisionist ideas among younger Anglican evangelicals. These ideas articulated new approaches to theology that contradicted the long-standing theological positions Packer had championed. In essence he’d lost the battle. “It persuaded Packer that the time had come to leave England.”14

Packer moved to Canada because his longtime friend James Houston, who had come to Vancouver earlier and became the principal architect of the newly founded Regent College, invited him to move here. Regent had developed from Brethren roots, and received its provincial charter in 1968. It opened its doors for the first regular semester in 1970, and placed a strong emphasis on providing graduate level theological education for lay people.

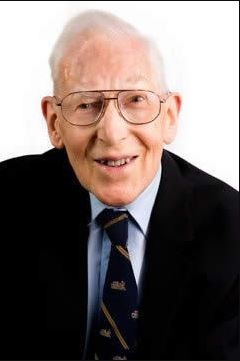

Packer could have had a number of other teaching positions in high profile seminaries in the United States, but he chose the fledgling Regent College, where 38 years later he is still involved – in his 91st year.

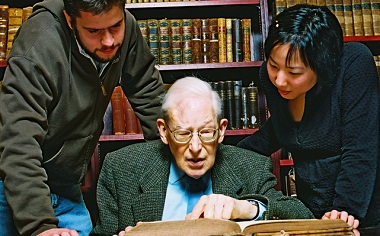

James Packer taught courses at Regent College this spring.

Packer’s long tenure at Regent has been a blessing to him, and to all who have come to study under him. And the icing on the cake, as he describes it, is his longtime association with Christianity Today, serving for decades in an editorial capacity, and in writing many articles. He has become well known as a leading figure among evangelicals in Canada, the United States and around the world.

Early on he made a deliberate choice to direct most of his writing toward the thinking layperson. This emerged from his conviction that theology should serve the church, that good spirituality is but the working out in life of good theology and that churches need biblically informed lay people. This has stood at the centre of his mission.

Controversy often surrounds religious leaders, and Packer has certainly had his share. It has taken its toll on him. He explains that he “is not a controversialist by nature but by necessity.”15 He had followed a bilateral policy – serving evangelical Anglicans as well as those in other denominations. Initially they all looked to him as a friend, but as a result of several controversies many deserted him and some severely criticized him for various associations and stands he took on issues.

Packer also followed a policy of “collaboration without compromise,” a position whereby he would cooperate with other Christian denominations on points in common without agreeing to doctrinal issues on which they disagreed. This became a serious controversial issue with Packer’s participation in a symposium called Evangelicals and Catholics Together (1994).

Perhaps the most tragic consequence of controversy was the Bishop of New Westminster’s revocation of Packer’s license in 2008. His uncompromising stand against the Anglican Church of Canada’s blessing of same-sex marriages led to his withdrawal from fellowship and his “suspension.”

However, Packer was “. . . relicensed by the Archbishop of the Southern Cone and received into the Anglican Church of North America.”16 He remains highly honoured, a leader to whom the members of this recently formed Anglican fellowship look for guidance.

Packer told his biographer Leland Ryken that he “never wanted to be a leader,”16 and had not cultivated it. He became a leader, however, by taking several leadership positions, a leading role in various movements, serving on boards and committees that made a permanent mark on evangelicalism, and through his teaching, writing and speaking. He never set leadership as a goal, but “. . . thought of [it] as a burden of responsibility generated by circumstances . . .”18

His leadership sprang from deeply rooted convictions about God, the Bible, doctrine and the church, and his determination to defend orthodoxy and tackle key theological issues in public debate, often entering into controversy that cost him personally. Yet these adverse reactions and deep wounds did not deter him from steering a straight and steady course, providing resources to fellow evangelicals who saw in Packer the champion of their movement.

Packer’s decision early on to write for thinking lay people helped catapult him into spheres of influence he would not have experienced had he stayed within the confines of scholarship and academia.

The term collaborator may well describe Packer’s most telling leadership quality. He loved working as a member of a team, and he did so on numerous occasions. Perhaps the best example was his role as general editor in producing the English Standard Version of the Bible. Interestingly, Packer himself sees this as his most significant contribution.

J.I. Packer’s star began to rise when, early in his career, he grabbed the attention of evangelicals in Britain and became a “go to” authority on biblical and theological issues. He extended his influence worldwide throughout his long career of teaching, speaking and writing, and remains a person of influence. As a naturalized Canadian he deserves a prominent place among truly great leaders in the religious world of Canada and the United States.

1 Alister McGrath, J.I. Packer, A Biography, (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House Co. 1997), 280

2 ibid, 9

3 ibid, 19

4 “Plymouth Brethren,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plymouth_Brethren

5 McGrath, 14

6 ibid, 63

7 Leland Ryken, J.I. Packer, An Evangelical Life, (Wheaton, Illinois: 2015), 82

8 McGrath, 86, 87

9 ibid, 116

10 ibid, 101

11 ibid, 109

12 ibid, 151

13 ibid

14 ibid, 217

15 Ryken, 410

16 ibid, 409

17 ibid, 116

18 ibid, 114

Neil Bramble is a freelance writer, editor and speaker living in Surrey. A teacher by profession, he joined the staff of The Gideons International in Canada and served for many years as editor of The Canadian Gideon. Packer was his staff advisor and systematic theology professor at Regent College in 1979. He holds the Master of Christian Studies degree from Regent College.

This article is re-posted by permission from Thread of 1000 Stories, an initiative of Faith in Canada 150 which features Canadian leaders whose leadership positions are inseparable from their faith. The profiles draw on the work done by senior editorial advisor, Lloyd Mackey in the Online Encyclopedia of Canadian Christian Leaders as well as presenting new stories from writers across Canada.