I began this series on ‘Christianity: a missionary religion’ in the lead-up to Mission Fest, both to remind people it was coming and to offer some insights into our rich missionary history and some of the issues and prospects as we move ahead.

I began this series on ‘Christianity: a missionary religion’ in the lead-up to Mission Fest, both to remind people it was coming and to offer some insights into our rich missionary history and some of the issues and prospects as we move ahead.

Mission Fest was a treat, over three days (February 15 – 17) at The Centre (Westside Church) in downtown Vancouver. Engaged participants visited dozens of exhibitor booths (for both local and international missions), worshiped and heard some good speakers. I gather there were about 1,000 young people at the Youth Encounter Friday evening.

The series

• Introduction

1. History of Missions

2. State of World Christianity

3. Specific Areas: Africa

4. Specific Areas: Asia

5. Specific Areas: Latin America

6. Not So Good News

7. New Approaches to Missions

I am looking mainly at some of the new books covering these various areas, but will also try to cover a few key themes along the way. It probably goes without saying that I will just scratch the surface of each topic – but I do hope that people will go on to read some of the books, which are of high quality.

V. Specific Areas: Latin America

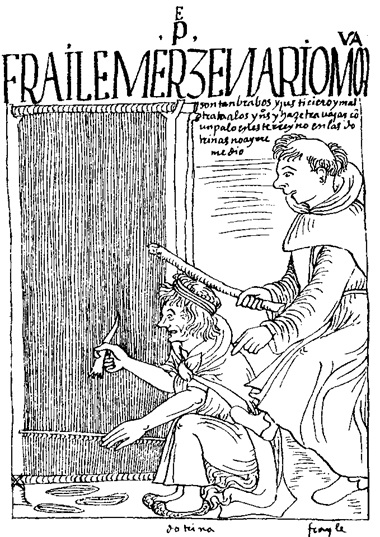

Drawing (ca. 1615) by Guamán Poma de Ayala depicting the friar Morúa beating a native worker. (Wikimedia Commons; public domain)

By chance, or maybe not, our family is reading the fascinating book-length ‘Letter to a King,’ written by Inca nobleman Guamán Poma (1535 – 1615), intended for the eyes of King Philip III of Spain. He hoped to let the ruler know about the damage that had been done to the people of the Andes under colonial Spanish rule.

Here is part of his ‘declaration’ in the book:

Your majesty, in your great goodness you have always charged your Viceroys and prelates, when they came to Peru, to look after our Indians and show favour to them, but once they disembark from their ships and set foot on land they forget your commands and turn against us.

Our ancient idolatry and heresy was due only to ignorance of the true path. Our Indians, who may have been barbarous, but were still good creatures, wept for their idols when these were broken up at the time of the Conquest. But it is the Christians who still adore property, gold and silver as their idols.

He also wrote:

Spanish couples who are blessed with big families spend all their days and nights dreaming about the gold and silver which their children are going to earn.

The husband says to the wife: “You can’t imagine how concerned I am, my dear, about our children’s education. To give them a good start in life, we must put them in the Church.

The wife answers, “Well said darling. Our son Iago can become a priest, and little Francisco can do the same. Then they’ll earn enough to let us have servants and give us lots of presents like partridges, chickens, eggs, fruit and vegetables. Later on little Alonso can be an Augustinian, little Martin can be a Dominican and little Gonzalo can join the Order of Mercy.”

There are many streams to Latin American Christianity, but it is worth remembering the salutary effect of key Latin American theologians at the pivotal 1974 gathering of the Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization (Lausanne ’74). As I noted in the Introduction to this series, “René Padilla excoriated American cultural captivity and its export around the world through missions,” pleading for “a more biblical Gospel and a more faithful church.”

Here are some recent books which offer glimpses into Latin American missions. Some of the write-ups will reflect my thoughts; others (in quotes) will simply be descriptions from the publisher.

- Samuel Escobar: In Search of Christ in Latin America: From Colonial Image to Liberating Savior (IVP Academic, 2019)

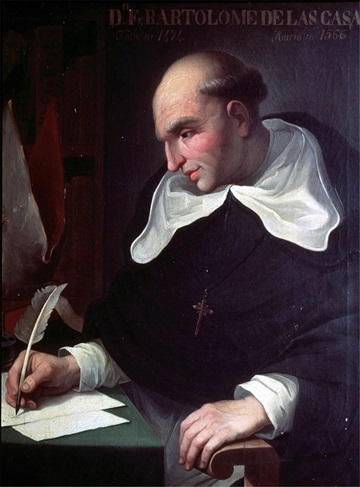

Bartolomé de las Casas was an exception to most missionaries to Latin America, who were unduly acquiescent to colonial authority.

Samuel Escobar was one of those Lausanne Congress theologians. In Search of Christ in Latin America is not primarily about missionary activity, but does include some some key insights. For example:

When the affirmation of Christ’s universality was connected to missionary outreach ‘from above,’ from the centers of power, and sometimes came intertwined with the European or North American colonializing enterprise, it was impossible to avoid a certain mark of triumphalism and imposition. . . .

Today’s Latin American missionaries do not carry the baggage of their country’s technological, military or political superiority; they are learning to do mission in the name of Jesus Christ ‘from below.’

René Padilla wrote the Foreword, highlighting the unique weaknesses of the Catholic and Protestant missionary movements:

[T]he Roman Catholic Church of the colonial period, with few exceptions, as in the case of Bartolomé de las Casas (1484 – 1566), did not produce a theology rooted in biblical teaching and with the prophetic force necessary to openly oppose the oppression of the indigenous people by the conquistadors.

In contrast to Roman Catholic Christianity, Protestant Christianity [arrived in Latin America] . . . with a predominant characteristic derived from the dominant culture [in Europe and the United States]: individualism. It is not surprising, therefore, that the churches resulting from the missionary movement of those countries would combine the valuable emphases of the Protestant Reformation (such as the centrality of Jesus Christ and the acknowledgement of grace as the basis and faith as the means of salvation) with a lack of appropriate recognition of the social and prophetic dimension of the biblical message.

A “theological awakening” only occurred in the 20th century; facing new realities which required both Catholics and Protestants “to seriously consider the theme of their present missionary responsibility.”

Escobar says:

Like those of the first century, they give themselves to the same task of crossing boundaries with the message of Gods kingdom: to serve the poor in Bangladesh or Algeria, to serve newborn Christian communities in Japan or New York City, to minister to immigrants enthusiastic in their faith in Germany or Spain.

A recent article in Christian Today describes that influx, saying there are now 4,259 evangelical churches in Spain, up from 2,944 in 2011. The growth is particularly strong in urban centres – Madrid (420), Barcelona (220) and Valencia (112). And Brazil is now one of the major missionary-sending nations worldwide.

- David C. Kirkpatrick: A Gospel for the Poor: Global Social Christianity and the Latin American Evangelical Left (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019)

A Gospel for the Poor offers some more context for Escobar’s book.

A Gospel for the Poor offers some more context for Escobar’s book.

“In 1974, the International Congress on World Evangelization met in Lausanne, Switzerland. Gathering together nearly 2,500 Protestant evangelical leaders from more than 150 countries and 135 denominations, it rivaled Vatican II in terms of its influence.

“But as David C. Kirkpatrick argues in A Gospel for the Poor, the Lausanne Congress was most influential because, for the first time, theologians from the Global South gained a place at the table of the world’s evangelical leadership – bringing their nascent brand of social Christianity with them.

“Leading up to this momentous occasion, after World War II, there emerged in various parts of the world an embryonic yet discernible progressive coalition of thinkers who were embedded in global evangelical organizations and educational institutions such as the InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students and the International Fellowship of Evangelical Mission Theologians.

“Within these groups, Latin Americans had an especially strong voice, for they had honed their theology as a religious minority, having defined it against two perceived ideological excesses: Marxist-inflected Catholic liberation theology and the conservative political loyalties of the U.S. Religious Right.

“In this context, transnational conversations provoked the rise of progressive evangelical politics, the explosion of Christian mission and relief organizations and the infusion of social justice into the very mission of evangelicals around the world and across a broad spectrum of denominations.

“Drawing upon bilingual interviews and archives and personal papers from three continents, Kirkpatrick adopts a transnational perspective to tell the story of how a Cold War generation of progressive Latin Americans, including seminal figures such as Ecuadorian René Padilla and Peruvian Samuel Escobar, developed, named and exported their version of social Christianity to an evolving coalition of global evangelicals.”

- David W. Bebbington, editor: The Gospel in Latin America: Historical Studies in Evangelicalism and the Global South (Baylor University Press, 2022)

“The shift of the center of gravity in world Christianity from the Global North to the Global South was arguably the most important development in the faith during the 20th century. One of the most salient dimensions within that broader evolution was the rise of evangelical Protestantism in Latin America, once a Roman Catholic stronghold.

“The shift of the center of gravity in world Christianity from the Global North to the Global South was arguably the most important development in the faith during the 20th century. One of the most salient dimensions within that broader evolution was the rise of evangelical Protestantism in Latin America, once a Roman Catholic stronghold.

“In the early 21st century a high percentage of Latin America was Pentecostal, but there had also been significant growth of other denominations, including Methodists and Baptists. By 2019 an estimated 19 percent of the population of Latin America identified as evangelicals.”

The Gospel in Latin America points out that at the time of the World Missionary Conference held in Edinburgh in 1910, “Latin America was then a largely barren land from an evangelical point of view.” A century later, “the region, having become the home of huge new denominations, was sending missionaries to some of the countries which in 1910 had been seen as the ‘home base’ of missions.’

One contributor, Daniel Salinas, again highlights the major contribution of René Padilla and Samuel Escobar to the work of Lausanne 1974 and beyond. He says the Latin American Theological Fellowship (Fraternidad Teológica Latinoamericana or FTL) should be considered alongside Liberation Theology as having had a major influence worldwide.

Martyrs

By far the best known missionaries to Latin America are Jim Elliott and his four partners who were killed during ‘Operation Auca’ in Ecuador. (The people once known as Auca are now called Waorani.) They were featured in publications such as Time, Life and Newsweek shortly after they were speared to death in the jungle.

The story continues to fascinate, with books commenting and speculating on the men and their movement still being released regularly. Here are a few recent publications:

- Kathryn T. Long: God in the Rainforest: A Tale of Martyrdom and Redemption in the Amazonian Rainforest (Oxford University Press, 2019)

- Joan Thomas: Five Wives (Harper Avenue, 2019)

- Elisabeth Elliott, editor: The Journals of Jim Elliott: Missionary, Martyr, Man of God (Revell, reissued 2020)

- Valerie Elliott Shephard: Devotedly: The Personal Letters and Love Story of Jim and Elisabeth Elliott (B&H Publishing Group)

Kathryn Long has written an impressive book which enlightens readers about the American missionary movement by focusing on a particular incident of martyrdom, the people involved in that outreach and the varied responses to it over the past 70 years.

Kathryn Long has written an impressive book which enlightens readers about the American missionary movement by focusing on a particular incident of martyrdom, the people involved in that outreach and the varied responses to it over the past 70 years.

“In January of 1956, five young evangelical missionaries were speared to death by a band of the Waorani people in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Two years later, two missionary women – the widow [Elisabeth Elliott] of one of the slain men [Jim Elliott] and the sister [Rachel Saint] of another [Nate Saint] – with the help of a Wao woman [Dayomae] were able to establish peaceful relations with the same people who had killed their loved ones.

“The highly publicized deaths of the five men and the subsequent efforts to Christianize the Waorani quickly became the defining missionary narrative for American evangelicals during the second half of the 20th century.”

In the Introduction to God in the Rainforest Long says:

The overarching argument is that the global expansion of Christianity as it happens on a case-by-case basis is complicated, even messy, much more so than either mythmakers or critics are willing to acknowledge. Missionaries make decisions with unintended consequences; indigenous people exercise agency in unexpected ways. . . .

The missionary-Waorani story also is fascinating because for years the inspirational accounts and even the biting criticisms have eclipsed the quotidian actions of people in Ecuador, both missionary and Waorani. Christianity may be demonstrated as much by a willingness to spoon liquid down the throats of people suffering from influenza as from feats of missionary heroism.

An old Wao warrior described himself as “a little believer” in the message of Jesus, meaning that he had a hard time understanding what the missionaries were talking about. Still, he learned enough over the years that he chose not to avenge his sister’s murder, though he clearly wanted to. His step in breaking a cycle of revenge may have reflected a spirit of sacrifice not unlike that of the missionaries he had killed years earlier on a riverbank in the rainforest.

Itota bey& t&nonamai. On behalf of Jesus, do not spear.

Five Wives is a really interesting read. A Canadian author who grew up with a couple of Elisabeth Elliott books in her home on the prairies has written “a fictionalized account of the real-life women of Operation Auca and their struggles – with grief, with doubt and with each other – as they continue to pursue their mission in the face of the explosion of fame that follows their husbands’ deaths.”

Five Wives is a really interesting read. A Canadian author who grew up with a couple of Elisabeth Elliott books in her home on the prairies has written “a fictionalized account of the real-life women of Operation Auca and their struggles – with grief, with doubt and with each other – as they continue to pursue their mission in the face of the explosion of fame that follows their husbands’ deaths.”

It is not clear exactly what Joan Thomas’s religious views are now, but she spoke of “the effects of this incursion on the Indigenous people” in a CBC interview. She was drawn back to the story when she read an article in The New Yorker about the politics of oil in Ecuador and understood that missionaries had been involved in harming Waorani interests.

Though inspired by the story as a child, she had certainly changed her mind, while retaining some empathy:

I was profoundly critical of [the missionaries] and I still am. But I think we’re kidding ourselves if we think we are so enlightened. We all live in our own bubbles. We’re all benefiting from the resource exploitation of the Amazon. I didn’t want to set myself up as being so profoundly different from them.

The book, though not the subject matter, has been warmly received by critics; Joan Thomas won the 2019 Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction.

One review in The Globe & Mail by Russell Smith gives a sense of its reception in some quarters; here is a portion:

Five Wives takes some frankly unattractive people as its subject, and presents them as purely well meaning. It is based on real events: The notoriously ill-advised Ecuadorian mission of a group of U.S. Christian evangelists in 1956 to convert an uncontacted tribe called the Waorani.

The mission resulted in five of the missionaries being killed in the jungle by the Waorani. The events then became celebrated in the world of American evangelism – not as evidence of the dangers of colonialism or religion, but as a heroic tale of bravery, sacrifice and martyrdom in the service of God. . . .

Thomas’s great skill is in making the baffling foreignness of imperialist religious zeal – unfamiliar to readers such as myself who didn’t grow up around it – if not sympathetic, then at least comprehensible. The belief of these people in the existence of pure goodness is reflected in their every action and thought. This book is 382 pages of living in the minds of crazy people, and it is a strangely reasonable place. God is behind everything: every daily event is a sign, a message to be interpreted. . . .

Thomas’s great skill is in making the baffling foreignness of imperialist religious zeal – unfamiliar to readers such as myself who didn’t grow up around it – if not sympathetic, then at least comprehensible. The belief of these people in the existence of pure goodness is reflected in their every action and thought. This book is 382 pages of living in the minds of crazy people, and it is a strangely reasonable place. God is behind everything: every daily event is a sign, a message to be interpreted. . . .

It is jarring to read such sensitivity from people whom I, in truth, think must have been, in fact, deeply stupid. Jarring, creepy, fascinating, humanizing. This exploration of the intelligence and sensitivity of outwardly conservative and unworldly people is, remember, Alice Munro’s great trick. Thomas’s remarkable feat of imagination puts her in Munro’s league.

Well, tell us what you really think! I can agree with Smith, and the GGs, that it’s a well written book; read it alongside some other books on the subject. There are many, including classics such as Through Gates of Splendor and Shadow of the Almighty by Elisabeth Elliott and Jungle Pilot (about Nate Saint) by Russell Hitt.

And they keep coming. The Journals of Jim Elliott and Devotedly: The Personal Letters and Love Story of Jim and Elisabeth Elliott are recent additions to the canon.

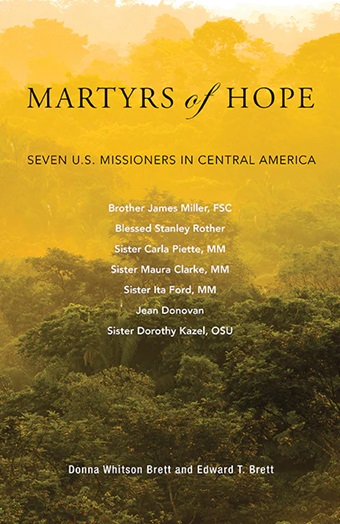

- Donna Whitson Brett & Edward T. Brett: Martyrs of Hope: Seven U.S. Missioners in Central America (Orbis Books, 2018)

Less well known, at least in my circles, is this story, which illustrates the range of circumstances in which Christian missionaries / missioners have been killed.

Less well known, at least in my circles, is this story, which illustrates the range of circumstances in which Christian missionaries / missioners have been killed.

“Martyrs of Hope tells the inspiring story of seven U.S. missioners who paid the ultimate price for the poor of Central America. Two of them have been beatified by the Catholic Church: Fr. Stanley Rother and Brother James Miller, who were killed in Guatemala.

“Four of them were women killed by the military in El Salvador: Maryknoll Sisters Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kazel and lay-missioner Jean Donovan. The seventh, Maryknoll Sister Carla Piette, who also died in El Salvador, represents what Pope Francis has recently called a “martyr of charity,” who laid down her life for her neighbors.

“All of these martyrs challenged an unjust status quo in the countries where they ministered. This book offers a riveting and troubling story of their heroic witness. Although their lives, backgrounds and beliefs varied widely, they held a common faith and hope: to better the lives of the poor among whom they lived and worked.”

Not to minimize the significance of the martyrs’ lives and contribution, but it is interesting to note the abstract about a paper by Rachel M. McCleary and Robert J. Barro (‘Opening the Fifth Seal: Catholic Martyrs and Forces of Religious Competition’), which begins:

Since Pope John Paul II’s stock-taking of 20th century martyrs, the Catholic Church has significantly increased the beatification and canonization of martyrs. Not only have the numbers of martyrs increased but the definition of martyrdom has expanded. Using a comprehensive new data set on Catholic martyrs (1588 – 2020), we argue that the Vatican’s recent emphasis on martyrs is a strategic response to competition with Protestants, especially Evangelicals.

Go here for more detail.

The Stott-Bediako Forum will look at ‘Transformation Revisited: Mission and Gospel Imagination’ in Medellín, Colombia (but also online), July 15 – 17:

The Stott-Bediako Forum will look at ‘Transformation Revisited: Mission and Gospel Imagination’ in Medellín, Colombia (but also online), July 15 – 17:

In the late 20th century, an increasing number of people, especially from the Majority World, started to reclaim and reimagine the concept of mission,’ seeking to be faithful to the witness of the early Church and the Biblical text.

These people recognized that the colonial and missionary histories of North America and Europe had often reduced and relegated the concept of ‘mission’ to the kind of verbal evangelism done by a small segment of the Church, crossing borders typically from the ‘Global North’ to the ‘Global South.’

This limited missionary imagination impeded a holistic understanding and witness of the gospel (i.e., Integral Mission), which involves the whole Church, embodying God’s kingdom in word and deed in every aspect of life on earth, as she dwells in and expands to and from all corners of the earth.

At least one of the speakers – Ruth Padilla DeBorst – has taught at Regent College, and another – Shadia Qubti – recently graduated from Vancouver School of Theology

Infemit, which is sponsoring the gathering, says of itself:

Feeling the dire need to grow in the integration of evangelism and social justice, to promote theology as a practice of the Whole Church that emerges from and informs daily life, as well as to give voice to churches in the non-Western world, an international group of evangelical theologians organized together to form INFEMIT to advance holistic, contextual mission theology not only for the worldwide evangelical community, but for the whole church.

Go here for more information.