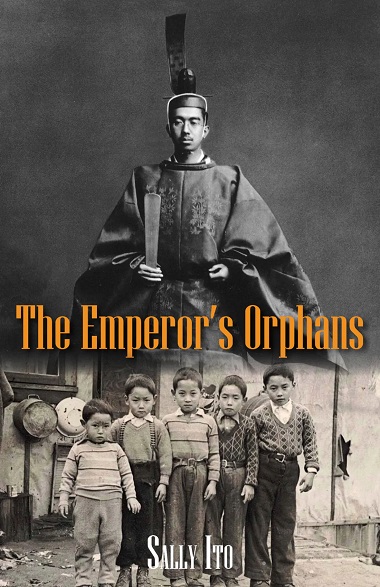

The Emperor’s Orphans is, in part, a metaphor for Japanese who are positioned between cultures – born or raised somewhere other than Japan, but still drawn deeply to their ancestral roots.

The Emperor’s Orphans is, in part, a metaphor for Japanese who are positioned between cultures – born or raised somewhere other than Japan, but still drawn deeply to their ancestral roots.

In telling her story, Winnipeg author Sally Ito combines the perspectives of branches of her family which chose very different paths.

First we have the stories she was told by her great aunt Kay, who spent World War II in an internment camp in the interior of British Columbia and thereafter settled on the Prairies.

Second, through the meticulous diaries and records kept by her maternal grandfather, Toshiro, for his descendants. He stayed in Japan, but visited Canada.

The third perspective is author Ito’s, who from her childhood begged for stories and treasured her grandfather’s printed records, even before she was able to read them in Japanese. She went on to research branches of the family and took a deep interest in their land, both in Japan and in Canada.

We are treated to exciting accounts of Ito’s great-grandfather Saichi recklessly fishing out of Richmond in the 1890s (he would make of point of going out during storms, so there would be less competition) and how he built a small fortune.

She describes a visit to what remained of aunt Kay’s lovely and fecund farm in Surrey – lost during WWII – along with stories of a visit to Slocan and Lemon Creek where the older generation were interned.

We read how her parents sojourned in the Northwest Territories (her father worked as a radio operator), of her family home in Sherwood Park, near Edmonton, and of her attachment to her aunt Kay’s farm in Opal, Alberta. Woven into all these glimpses of Canadian homesteads are trips back to Japan, and the land and houses and family of the relatives who stayed in, returned to and visited the home country, Japan.

Reading The Emperor’s Orphans felt like an odd mirror to my own life: growing up in Japan as the child of missionary parents, and even in adulthood feeling the pull toward Japanese culture. Ito’s appreciation

of the daily beauties of Japanese culture is my own.

Last fall we hired my former Japanese flower arranging teacher to guide us so we could decorate for my daughter’s wedding to a second-generation Japanese-Canadian. The groom had also taken lessons and

joined in. Last year I hired a professional kimono maker and teacher to help me sew a kimono for my eldest grand-daughter. Most of my closest friends are Japanese-Canadians. I taught Japanese in a public high school for 25 years.

Japan does not let us go. I also sometimes feel that crushing sense of ‘duty’ – and, like many of Sally’s ancestors, have generally fought it.

Sally Ito

Ito’s last chapter on the search for her grandfather Saichi’s land is at times painfully detailed, but it reminded me of the crucial point in my father’s work in Japan.

He was trying to buy land; the legalities were so convoluted that he began to see it as a crisis in his ministry. He could get the land and do violence to his conscience, but then he might as well give up on his ministry – how could he ever encourage people to trust God with the difficult things in life?

It was heart-warming to see Ito choose to give up her branch of the family’s right to Saichi’s land for what could be seen as a generous and greater purpose – to support someone who had, out of the sense of duty to his ancestors, taken on a familial burden.

Sally Ito does not spare herself or her relations. The Emperor’s Orphans is an honest, inside look at a courageous family.

This article was first published in the Imago Arts newsletter and is re-posted by permission.