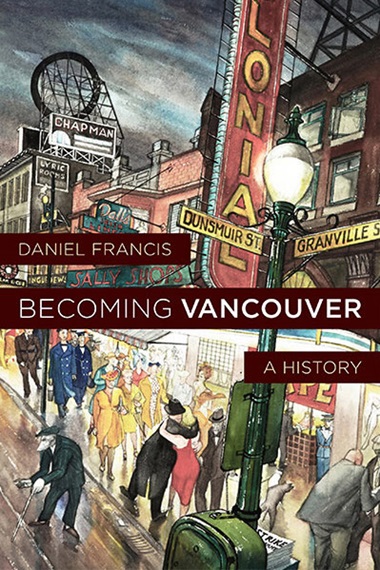

Daniel Francis: Becoming Vancouver: A History (Harbour Publishing, 2021)

Daniel Francis: Becoming Vancouver: A History (Harbour Publishing, 2021)

I should have written this long ago – but fortunately everything in this book is old news anyway. And they say you can learn from history.

For example, it may soon come in handy to be reminded that Vancouver has in fact won the Stanley Cup – in 1915. Or that the fire season in 1886 was worse than this year is projected to be – most of the city burned to the ground. Or that the poor folks planning to move into the new Shaughnessy Heights neighbourhood in 1909 were faced with “a requirement that no home cost less than $6,000, six times what a middling house cost elsewhere in the city.”

Vancouver artist/author Michael Kluckner said of Becoming Vancouver:

Daniel Francis has written the first complete, chronological history of Vancouver in half a century, bringing the story up to date with engaging accounts of Indigenous life, as well as local politics, entertainment and crime that show the city in all its glory.

Francis is writing for a broad audience. Each of the eight chapters covers roughly 20 years or Vancouver’s history between the building of Hastings Mill on the south shore of Burrard Inlet in 1865 until 2020. (The mill survived the 1886 fire and now houses a small museum at the foot of Alma Street in Point Grey.)

Writing in BC Studies in early 2023, John Belec said:

Becoming Vancouver is organized chronologically and is character-driven. Fortunately for the author, Vancouver offers an abundant supply of characters from which to draw, some with familiar names, such as Gassy Jack, Cornelius Van Horne, Joe Fortes, Gerry McGeer, Tom Campbell and Arthur Erickson. However most of the cast will likely be new to the reader.

August Jack Khatsahlano, his wife Swanamia (Marrian) and a child in a dugout canoe, looking east at Kitsilano Indian Reserve in 1907. City of Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-203

Francis begins the book with August Jack Khahtsahlano who was born in 1877 in the village of Sen-ákw [Snauq], located at the mouth of False Creek.

The forced relocation of Khahtsahlano to the Capilano Reserve in North Vancouver establishes a context: Vancouver is built on stolen land: “mainstream Vancouver . . . removed the Indigenous people who originally lived within the city’s borders and pretty much erased them from its memory.” (223).

Here are just a few highlights from the book:

Emily Carr painted ‘Indian Encampment, Vancouver’ based on the shores of False Creek during her time in Vancouver from 1906 – 1910.

• Indigenous land: When August Jack Khahtsahlano was asked “How many Indians do you suppose lived around Burrard Inlet and English Bay before the white man came,” he responded, “About a million!” Possibly exaggerated for effect, Francis notes, but the point was made. Khahtsahlano added: “There was a settlement at E-yal-mough (Jericho), another at Snauq (Burrard Bridge), at Ay-yul-shun (English Bay Beach), at Stait-wouk (Second Beach), at Chay-thoos (Prospect Point), at Xway’xway (Lumberman’s Arch), at Homulcheson (Capilano), at Ustlawn (North Vancouver, at Chay-chil-wuk), Seymour Creek . . .” Francis benefits from Jean Barman’s Stanley Park’s Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point, which I wrote about here.

Dupont (now Pender) Street in 1904, then as now the centre of Chinatown. Philip Timms photograph, Vancouver Public Library

• Chinese immigrants suffered racism in a number of forms, but one sometimes-overlooked source of animosity was workers and unions who feared losing jobs and benefits: “John McDougall was public enemy number one during Vancouver’s earliest days. McDougall was a contractor who specialized in land clearance. People in town called him ‘Chinese’ McDougall because he insisted on employing Asian labourers (at half the wages he paid anyone else), despite the fact that the white majority wanted the ‘Celestials’ gone from the community.”

• Drug use is not a new problem in Vancouver. “By the early 1920s the Chinese were blamed for the spreading problem of drug abuse and for corrupting young white men and women by seducing them into Chinatown drug dens.” Won Alexander Cumyow (whose image in now being considered for the next $5 bill) refuted those claims. “In 1958 Maclean’s magazine dubbed [an intersection just down Hastings from Main] ‘Canada’s most notorious underground rendezvous.’ The Maclean’s reporter paid a visit to Harry Rankin, then a young lawyer but soon to be one of the city’s longest-serving aldermen, who gazed down ruefully from his office window and declared ‘it’s not a street anymore, it’s a scene from Gorky’s Lower Depths.'”

Well-off Vancouverites lined up to buy houses in the new Shaughnessy Heights development in 1909. CVA 677-526, City of Vancouver Archives.

• Dramatic growth has been an ongoing theme in Vancouver. Artist Emily Carr wrote before World War I: “Vancouver was then only a little town, but it was growing hard. Almost every day you saw more of her forest being pushed back, half-cleared, waiting to be drained and built upon – mile upon mile of charred stumps and boggy skunk-cabbage swamp, root-holes filled with brown stagnant water, reflecting blue sky by day, rasping with frog croaks by night, fireweed, rank of growth, springing from the dour soil to burst into loose-hung, lush pink blossoms, dangling from red stalks, their clusters of loveliness trying to hide the hideous transition from wild to tamed land.”

• Bicycles: Vancouver really was a bicycle city at one time: “Major Matthews [Vancouver’s first archivist] said that by 1900 a bicycle “craze” had hit the city: “The ‘machines’ were so numerous that City Council ordered special bicycle paths constructed on those streets which were most frequently used.” However, before too long bikes were largely replaced by the streetcar and automobiles as the main mode of urban transportation.

• Pandemic: Just over 100 years ago, Vancouver suffered through a major pandemic: “Demobilized soldiers returning from Europe brought with them the deadly infection, known as the Spanish flu. . . . Dr. Underhill [Vancouver’s medical health officer] gave in to mounting public alarm and declared the city ‘closed,’ meaning that a ban was placed on public gatherings [including churches] and most businesses locked their doors.” Over about six months, from October 1918 to April 1919, some 900 Vancouverites died of the flu.

•

A parade through Japantown in the 1930s. City of Vancouver Archives

WWII internment: It is quite well known – but valuable to be reminded – that Japanese Canadians were forced from their homes and relocated to camps in the Interior or across Canada during World War II: “‘After the war,’ recalled Japanese Canadian resident George Nitta, ‘Powell Street [Japantown] was nothing but a ghost town.'” Italian Canadians were affected as well. Some men were interned in Alberta and the east, and “about 1,300 local Italians who were considered enemy aliens were required to report monthly to the RCMP for the duration of the conflict.”

For those of us who are a little bit older, and have been around the city for a while, there will be personal points of contact to events mentioned in the book.

In my case, I recall the Town Fool (Joachim Foikis) coming to visit us at Lord Byng High School; picking up garbage (for the city) on Granville Island when it was still one of False Creek’s “prime industrial areas”; waving off Greenpeace’s Phyllis Cormack at Jericho as it sailed to Amchitka in 1971; hitchhiking up the hill to my home in Point Grey (where Francis also grew up, attending Lord Byng) with then-major Mike Harcourt; articling with the above-mentioned Harry Rankin; and taking part with our young family in a massive mid-80s peace march from Kitsilano across Burrard Street Bridge to the West End.

Of course, one forgets, or never knew, much of what went on, so Becoming Vancouver fills in many gaps.

Religion?

I do have one issue with Becoming Vancouver. Francis has done a good job reminding us of several overlooked elements of our history. But not with religion.

What has he not covered, religion-wise? Pretty much everything. Despite noting that “Vancouver devours its own history” and that “as a historian, I am unsympathetic to this exercise in urban memory loss,” he more or less ignores our spiritual heritage.

Joe Fortes, the ‘mayor’ of English Bay, taught generations of people to swim. Vancouver Public Library 83598

Religion doesn’t warrant a mention in the Index. There are some tidbits along the way – Rev. Andrew Roddan and First United Church (properly) get a couple of mentions for their social gospel presence in the Downtown Eastside; Christ Church Cathedral is referred as the site of Pauline Johnson’s funeral; the Women’s Christian Temperance Union is noted not for its contribution to women’s suffrage, but for a letter of complaint about a “breach of etiquette” in the ‘Great English Bay Scandal,’ which involved a woman showing a little too much flesh (up to her knee) while swimming with (too close to) English Bay’s famous lifeguard, Joe Fortes.

There is no interaction with works about our religious heritage. In the book’s list of Sources, for example, Robert Burkinshaw is cited for his False Creek work, but not for his important Pilgrims in Lotus Land: Conservative Protestantism in British Columbia, 1917 – 1981.

Nor does Francis point to books such as Infidels and the Damn Churches: Irreligion and Religion in Settler British Columbia (Lynne Marks) or Asian Religions in British Columbia (DeVries et al).

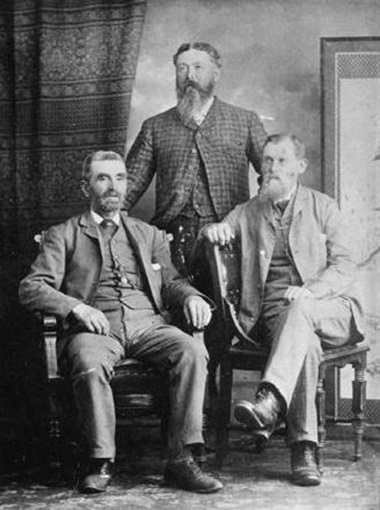

John Morton (right) was one of ‘the Three Greenhorns,’ who originally owned the West End; he was also very active as a Baptist. J.D. Hall photo, City of Vancouver Archives, AM54-S4-: Port P775

There is no discussion of key denominations such as the Roman Catholics, Anglicans or United. Big churches – Broadway, Coastal, Westside – are not mentioned. Significant figures, institutions and movements are overlooked, including Bernice Gerard (about whom UBC Press will publish a book this fall), Bob Birch, the Bentalls, Union Gospel Mission, the Salvation Army, Vancouver School of Theology, Regent College and the Charles Price evangelistic meetings in the 1920s. . . .

Some key players do appear, but their Christian faith – which was central to their lives – is not mentioned. For example, though John Morton is recognized as one of ‘the Three Greenhorns’ who originally owned and saw the potential of much of what is now the West End, Francis does not mention his key role in supporting BC Baptists and their churches.

One might imagine that Francis is anti-Christian, but other religions receive barely a mention either. Francis does cover one stain on Vancouver’s history, the Komagata Maru incident, in which authorities refused the mostly Sikh passengers permission to disembark.

Nonetheless, I’ll admit that retired history professor Patricia Roy made a valid point in The British Columbia Review: “In 250 or so pages, Francis could not possibly cover every aspect of the city’s history so listing omissions may be quibbling, but there are some imbalances.” She points to lacks and/or imbalance with regard to the arts, education and sports.

The City of Vancouver officially observes Komagata Maru Remembrance Day each May 23. Photo from its site.

Roy concluded, though:

Let us hope that this excellent book – likely to be the ‘standard’ history of Vancouver for some years – will inspire more Vancouver residents, both new arrivals and old timers, to have greater respect for the city’s natural beauty and its historic built environment.

John Belec, writing in BC Studies, agreed, saying: “In Becoming Vancouver, Daniel Francis has written the definitive story of Vancouver.”

So, the book is well worth reading. Now will someone please write a companion volume on Christianity (maybe religion?) in Vancouver.

A couple of other good books to follow up with:

- Michael Kluckner: Surviving Vancouver (Midtown Press, 2024)

- Eve Lazarus: Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020)

In my post above, I practiced a little ‘tongue in cheek’ in communicating that I could not quite recall who wrote the church ‘walking tour’ piece. The point I wanted to make was that Chuck Davis knew that churches and other religious institutions were important to Greater Vancouver’s history. There were many west coast journalists who could have written the story. Chuck had the wisdom to see that churches mattered. I was honoured that he asked me to say so.

Your comments with respect to the lack of religious context in the Francis book brought to mind another tome, a coffee table volume by the late and beloved Vancouver journalist, Chuck Davis, entitled The Greater Vancouver Book, published in 1996.

It had a fairly detailed section that could be described as a ‘walking tour’ of Vancouver area churches with some interesting asides that brought various sectors of the Christian faith community into a broader context. I cannot quite recall, at the moment, who wrote that particular part of the book. In 2011, a year after Chuck’s death, the book was updated and re-released as The Metropolitan Vancouver Book. I do not know if the church section was included.

Thanks for this review. To your latter points, it’s ironic the author perpetuates the erasure of important stories by writing his book from a 21st century lens and not from the vantage point of what was considered important within the eras he writes. Also, like you, I’d be very interested in reading a book on the Christian history of this city.