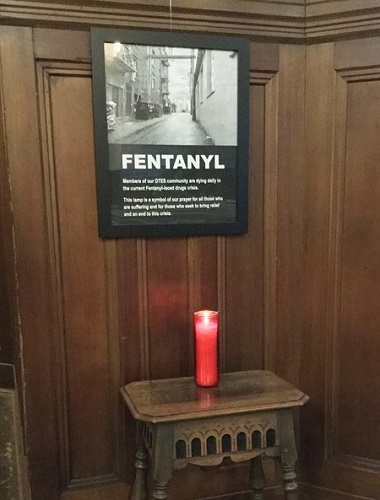

St. James Anglican Church and Fr. Matthew Johnson’s Street Outreach Initiative have created a Fentanyl Memorial in the church’s sanctuary.

Fr. Matthew Johnson serves in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside with the Street Outreach Initiative, a joint program of the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster and St. James Anglican Church.

British Columbia finds itself in a life and death crisis. All around us, fellow citizens are dying. Men, women and teens. Their humanity – now cold, still, lifeless – removed from our midst. This is the opioid overdose crisis. And it is killing two British Columbians every day.

Opioids are a class of drug derived from opium, used to relieve pain. They include morphine, codeine, heroin, methadone, oxycodone and hydrocodone. There are also synthetic opioids, most notably fentanyl and carfentanyl. This class of drugs is extremely addictive. And when an overdose is taken, it can be deadly.

It is easy to diminish this epidemic as something affecting only drug users on the street. People mistakenly caricatured as ‘out there,’ different from us, and somehow less worthy of respect.

This, however, is not the case, for opioid addiction affects all manner of persons. In the language of the Book of Common Prayer, “all sorts and conditions of men.”

It is possible that you are personally acquainted with someone whom you do not know is addicted. Many addicts have stable lives, hold down responsible jobs, and function effectively in day-to-day life. Some people become addicted following medical problems or surgery, for which opioids may be prescribed. Even short-term use of opioids can result in dependency.

There is also a class of opioid users who are not addicted. ‘Recreational users’ may use opioids on an occasional basis, most typically on weekends. This includes middle class people, and the more affluent. It is interesting that the highest number of overdose fatalities occur on weekends. And it is not just injection drug users who are dying. Overdose with opioids can occur equally with orally administered drugs in pill or tablet form.

Fentanyl

Death by overdose is nothing new in BC. What is new is the vast increase in the number of fatalities. Figures provided by the BC Coroner’s Service are staggering. In the first 11 months of 2016, 755 people died by opioid overdose. In 2015 443 people died. That’s a 70.4 percent increase in deaths.

This alarming increase is due to fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, which drug traffickers add to heroin and other drugs to increase overall supply and therefore maximize profits. Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more powerful than heroin.

The danger of fentanyl, when added to another drug, is that it becomes difficult for injection drug users to gauge the overall potency of a single dose. When adulterated by fentanyl, an amount of heroin that might normally be safe to inject can easily contain a more powerful dose than anticipated. The result is overdose, sometimes fatal.

Fentanyl is also used in counterfeit pills labelled as oxycodone or other opioid pain killers. The pills look like the real thing, but contain fentanyl, sometimes in lethal amounts.

A study by Insite, the safe injection facility in our parish, found that 90 percent of the heroin tested contains the additive fentanyl.

Fentanyl has also been detected in drugs like cocaine and the party drug ecstasy (MDMA), both of them popular with those who are not street involved.

Street ministry

Fr. Matthew Johnson on the street. Photo from Outreach Initiative page on Anglican Diocese of New Westminster website.

On the streets of the Downtown Eastside, where I work, fentanyl stalks our neighbourhood like the reaper. Every month, on and just after cheque issue day, there has always been a slew of opioid overdoses. Ambulances screaming by for two or three days in a row.

With the advent of fentanyl, the sirens are constant throughout the month. Ambulances, their lights flashing and strobing, can be seen on streets and in alleys numerous times every day. It is never-ending.

I started to notice the increase in deaths about a year and a half ago. People on the street, who I knew for years, started to turn up dead. Others reported they were losing their friends and family members. I started to attend and participate in more memorial services. And on the street, I witnessed more overdoses.

I work with many people addicted to heroin or other drugs. People of infinite value in the sight of God. And I worry about them. Having already lost many acquaintances, the question is: Who will be next?

On daily ‘rounds’ on the street, I carry a pack with everything from holy water and prayer cards to hemostatic bandages. To this I have added a naloxone kit, containing three syringes and three phials of naloxone.

Naloxone is an antidote to opioids and can reverse an overdose in a matter of seconds. It is injected intra-muscularly, usually in the upper arm or thigh. Along with artificial respiration, this can save a life. Although I have dealt with overdoses in the past, I have not had to use naloxone yet. But it is at the ready at all times, one more part of the street ministry toolkit.

Making a difference

The most effective preventative measure against overdose is to remove the shame associated with drug addiction.

The behaviours associated with addiction – any addiction – are self-destructive, it is true. Drug users need to be supported at each step in the process of addressing addiction and seeking recovery.

But nothing is gained by stigmatizing those who struggle with addiction. Shame and stigmatization make it difficult if not impossible for users to disclose their addiction to family, friends and people who care. They use in secret and alone. And they die alone.

Indeed, during this fentanyl and opioid crisis, many have been shocked by the overdose death of someone they knew well and would never suspect was using drugs.

If you know or suspect that a friend, family member, co-worker or other acquaintance is using drugs, establish a relationship where they know they will not be judged or condemned if they speak openly about it. A guideline to this is provided in the words of the Baptismal Covenant, in which we promise to “respect the dignity of every human being,” whether we agree with their choices or not.

When appropriate, speak about the following overdose prevention strategies:

- do not inject or consume drugs alone, where overdose will go undetected

- do not mix drugs

- use a supervised injection facility where available

- obtain a naloxone kit to use if you suspect an overdose

- call 911 if you suspect an overdose

The establishment of supervised injection sites also saves lives. Note, these programs are not about condoning drug use. A decade ago, I had initial misgivings about the supervised injection facility in our parish. I was concerned that it might somehow normalize self-destructive behaviour.

On reflection, I concluded that honouring life first means preserving life. These sites preserve life by preventing overdose deaths and preventing the transmission of HIV and Hep-C. If a person is to ever have a chance to address addiction and pursue recovery, they must first be alive.

For your part, if you know or live with someone who uses drugs, obtain naloxone training and keep a naloxone kit, so that you can take direct action if an overdose should occur. Naloxone kits are available at a cost, without a prescription, from pharmacies in your community. Pharmacists can provide training at the time you purchase it. See this website for more information.

This op/ed, written in mid-December, will be available in the February issue of Topic, the publication of the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster. It is re-posted by permission.

Christ Church Cathedral, also part of the Anglican Diocese, hosted Johnson and others for their Conversations4Community gathering January 25, in order to “learn more about the facts and implications of the fentanyl overdose crisis and how we individually and collectively might best respond with compassion and love.”

CBC Radio host Stephen Quinn will host a ‘Fentanyl Fix’ Forum January 31, asking ‘What policies and practices are necessary to reduce this epidemic?’ Quinn will be joined by policy makers, medical experts, addicts and family members who have lost loved ones for a discussion focused on solutions.