Will Wilding spent 40 years as an influential architect in Vancouver, putting his stamp on the design and construction of churches throughout the province (see the accompanying story).

Will Wilding spent 40 years as an influential architect in Vancouver, putting his stamp on the design and construction of churches throughout the province (see the accompanying story).

But that future was surely never imagined by him or his family in his early days. The spiritual nature of Wilding’s work might have derived from growing up in a missionary family, though his exposure to Modernist influences must have been minimal.

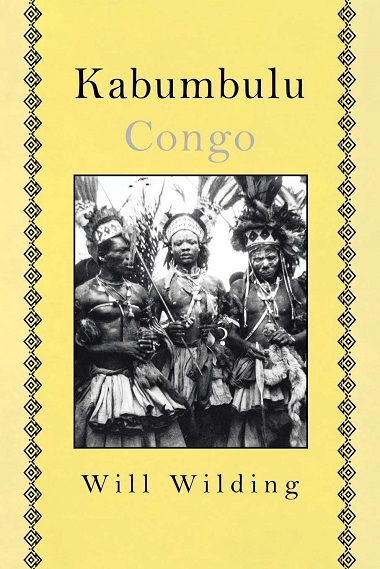

Wilding recently published a book describing his experiences as a child in Africa. Kabumbulu Congo recounts the story of his family living in the southeast corner of the Belgian Congo between 1914 and 1935.

The youngest of Robert and Martha Wilding’s three children, he spent his first eight years in Kabumbulu, before moving to Cape Town, South Africa for further education.

He said that while many memories are faint, “the stories, songs and pictures of the Lubaland left a deep impression on me as a child that has lasted throughout my adult life.”

Focus on parents

Although Wilding would have been too young to fully appreciate much of the work his parents were doing, he does provide some insights.

The Wilding family (Robert and Martha, with Will, Pearl and Alf) on the verandah of their home where, apparently, cannibals sometimes came to dance.

Regarding his father, for example, he writes:

Eventually, the vast work of translating parts of the Bible was undertaken by my father with John Clark and a team of Africans. This translation work was started in 1917 when he established a mission in Kabumbulu . . .

My father spent many years on the work, and after we moved to South Africa, he returned for a year to complete the first five books of the Old Testament.

About his mother, he says:

My mother set herself to the task of [medical work] as a priority. The Belgian government supplied medications for the many ills such as malaria, blackwater fever and other diseases. Once the Africans learned to trust the missionaries, the lines would extend far down the hillside. Word would be sent by means of the effective native drum.

The Kabumbulu hospital was built on a hillside close to our house. It was designed as a village where family who brought the sick could stay, help the staff and prepare meals. The location was chosen because of shade trees.

A couple of elements of the book appealed to me particularly – the description of faith missions and the influence of an earlier generation of missionaries.

Faith missions

Unfortunately, many people will have developed their sense of missions in the Congo by reading The Poisonwood Bible (as I am doing right now). Very well written, it leaves a most unpleasant aftertaste regarding the missionary enterprise. The more fortunate, many fewer in number, no doubt, may have read Helen Roseveare’s inspiring works.

(I was fortunate enough to meet some missionaries who had been forced out of the southeast corner of what was then Zaire (formerly Belgian Congo, now Democratic Republic of the Congo) during the late 1970s. They were being hosted by a family with whom I was staying – and where I became a Christian – in Zambia. It wasn’t the first time they had had to move their family out to avoid violence. They impressed me.)

Kabumbulu Congo offers insights into one family’s experiences, though they did broadly represent the faith missionary movement. Those who went overseas in this way displayed real courage, and considerable confidence in God’s provision

In the preface, University of Cambridge professor David Maxwell states:

Missionaries were a very different type of expatriate from colonial administrators, prospectors and traders. They learned local languages and lived in proximity with African communities, often for decades.

They made mistakes and sometimes misread indigenous culture, but the images in this book suggest that they were also able to cultivate friendships – relationships of intimacy and trust – upon which local churches were founded.

He adds, referring to Open Brethren missionaries:

Brethren missions were formed in reaction to the work of established missionary societies and their programs of commerce, civilization and Christianity.

Particular concerns were raised about the bloated establishments, churches and chapel buildings; missionary housing; and the employment of teachers and medical missionaries. Critics demanded simplicity and turned to the Brethren for models of governance out of which the faith mission emerged. . . .

Professional fundraising activities were deemed unnecessary because gifts would be supplied through faith in God’s provision. . . . The promotion of Western culture with Christianity was to be avoided. Released from direction by home committees, and wholly nondenominational in approach, missionaries were to assimilate themselves to indigenous modes of living.

Thus, new faith missions deliberately sought isolated and unfamiliar territory, far from the contaminating influence of European colonialism and preexisting missions, usually called “regions beyond” in missionary literature.

Missionary models

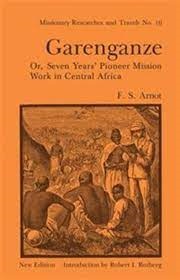

The Wildings followed in the footsteps of Frederick Stanley Arnot.

Wilding’s parents were strongly influenced by a couple of pioneer Scottish missionaries. Robert was “deeply challenged to consider becoming a missionary” when he read David Livingstone’s journals while serving in the Royal Navy.

Livingstone also had a major impact on Frederick Stanley Arnot, who “established a chain of missions from the coast of Angola into the interior.”

After Robert had decided to devote his life to missions, he studied at Livingstone College near London. While there, he heard Arnot speak, and that played a large role in helping him decide where he should serve.

An entry in The Evangelical Dictionary of World Missions includes this description of Arnot:

He was a peacemaker to King Lewanika of the Barotse, and dissuaded him from attacking the white settlers. After working in Angola, he went in 1885 to the Belgian Congo, invited by King Mushidi of Garenganze and there established a mission station.

Like Livingstone, Arnot was criticized both for his independence (he was linked to no missionary society and happily helped colleagues of other denominations) and for doubling as an explorer, which brought him a fellowship of the Royal Geographic Society.

Arnot nevertheless established many mission stations, despite multiple obstacles including disease and lack of food and water. His example brought other workers . . .

A more extensive description of Arnot and his legacy can be found in the Dictionary of African Christian Biography.

Kabumbulu Congo is particularly admirable in placing Wilding’s family in the context of broader missionary activity in the region. Wilding has left several books by and about Arnot to his family archive, along with others, including:

Kabumbulu Congo is particularly admirable in placing Wilding’s family in the context of broader missionary activity in the region. Wilding has left several books by and about Arnot to his family archive, along with others, including:

- Back to the Long Grass (Dan Crawford)

- Thinking Black (Dan Crawford)

- Dan Crawford: Missionary and Pioneer in Central Africa (George Edwin Tilsley)

- Dawn in the Dark Continent (James Stewart)

- Turning the World Upside Down (W.T. Stunt)

- African Footprints: A Sixty Year Safari (Zelma Virgin)

I wish more families would point their heirs to our missionary history. Wilding’s book, and the others he mentions, are a treasure.

Several thousand words

Photos (which take up a good portion of the 110 page book) tell much of the more personal side of Wildings’ story – the three children with African children, a Luban bridal party, young marauding lions killed by villagers, a 1915 ‘welcome’ to Garenganze, his mother in a nursing uniform, women gathered for Bible study . . .

Photos (which take up a good portion of the 110 page book) tell much of the more personal side of Wildings’ story – the three children with African children, a Luban bridal party, young marauding lions killed by villagers, a 1915 ‘welcome’ to Garenganze, his mother in a nursing uniform, women gathered for Bible study . . .

“Missionaries took many photographs.” Maxwell notes, adding that some of those images – disfigured people and animals killed by the local people, for example – “will doubtless shock modern viewers.”

The pictures were not just for family consumption. They were also for the home audience, in part to educate and inspire, but also to help raise funds, and prayers, for the faith mission.

Unique heritage

Is there any link between Will Wilding’s missionary upbringing in the Belgian Congo and his 40-year career as an architect in Vancouver? Hard to say, though a pioneering spirit, a desire to avoid worn out forms and practices and a strong streak of perseverance, do show through.

“My connection with designing such buildings was the example my father gave in doing the same in the Congo,” he emailed me, which suggests the wide variety of activities one must undertake as a pioneering missionary.

Will Wilding is a man of independent character, and it is good to know that he can look back on both his family’s missionary service and his own creative efforts, surrounded by family, in his old age.

Thank you! I’ve ordered the book.

So grateful to have read this.

Rob Visser