Glenn Smith will be in town February 5 to lead a training session on how to ‘read’ your neighbourhood.

Glenn Smith will present How to Read Your Neighbourhood: 20 Steps for Assessing Your Missional Context next Thursday (February 5) at Salvation Army Divisional Headquarters in Burnaby. Following is an interview he did in Missional Voice, published by Forge Canada, which is re-posted by permission.

Missional Voice: Thanks, Glenn, for taking the time to talk with us this morning. Could you tell us a bit about Christian Direction? What is it and what kind of work are you up to?

Glenn Smith: Christian Direction is a multifaceted, metropolitan ministry that works in Quebec. We have teams of people that work in boroughs on the island of Montreal in partnership with congregations and social service agencies.

We are committed to the social and spiritual transformation of these neighbourhoods, beginning with kids – we have a bias in our work toward kids and their families. But we have learned over time the importance of seeking the social and spiritual transformation of communities as well. We have learned that one cannot divorce the social and spiritual transformation of people from the social and spiritual transformation of the milieu in which they are found.

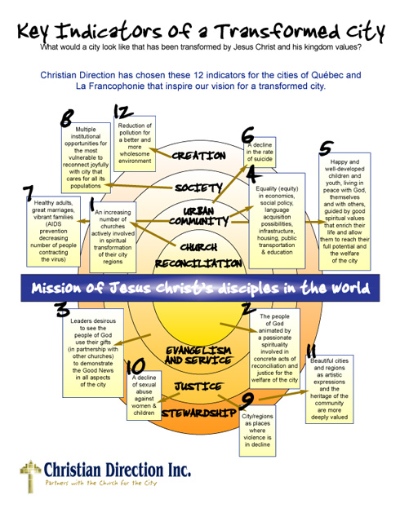

We also do research, lay-equipping, and theological education in large cities in the francophone world. What we are best known for is our indicators of a transformed city.

MV: When you talk about the well-being of the neighbourhood, what are these indicators? How did you discover these?

GS: The vision of Christian Direction is that we want to see God transform urban communities by the concerted actions of committed Christians. In a staff meeting in 2005, I asked my colleagues, “what would it look like if God did it? What does community transformation look like?”

This led to extended research – engaging churches, neighbourhood groups, our board – and that is when we came up with the 12 indicators. They now help us pay attention to how we might attend to the peace and well-being of the city. We know now of over 100 churches and communities around the world that have drafted their own indicators. We have definitely taken the approach that encourages churches and communities to not photocopy our indicators – don’t copy what we said, but do what we did.

This led to extended research – engaging churches, neighbourhood groups, our board – and that is when we came up with the 12 indicators. They now help us pay attention to how we might attend to the peace and well-being of the city. We know now of over 100 churches and communities around the world that have drafted their own indicators. We have definitely taken the approach that encourages churches and communities to not photocopy our indicators – don’t copy what we said, but do what we did.

MV: Neighbourhood and place is obviously very important to you and your work. What are some of the theological and missiological reasons for your focus on neighbourhoods?

GS: I first became interested in Montreal back in 1975 when I was working with Christian Direction to partner with churches and denominations and nonprofits that were going to do an outreach in Montreal during the Olympic Games in 1976. I began to study neighbourhoods to assist this outreach and I began to see some patterns in Montreal that really interested me.

Later, when I did my doctoral studies at the end of the 1980s, I worked with Roger Greenway, Harvey Conn and Ray Bakke. It was at that time that we coined the term ‘exegeting the neighbourhood.’ We began to say that what we do hermeneutically in the scriptures is what we need to also do hermeneutically to understand the city. Our biblical hermeneutic and our social hermeneutic need to have the same underpinnings.

What I mean by this is that the same cultural, historical and narrative attention that we give to understanding the scriptures – reading them in light of God’s ongoing work in the world but also in their original context – we also need to bring to the neighbourhood. We need to understand our neighbourhoods, their history, culture and narratives on their own terms. We need a biblical and social hermeneutic.

MV: What role does research play in your work with neighbourhoods and churches?

GS: Research is a big part of what we do because it lets the context shape the things we do. We will not do anything in a neighbourhood without first doing research because we’ve learned the hard way that new initiatives without a community assessment and exegesis gets us into all kinds of trouble. The research helps us to understand what we should do, but it also creates a network of congregations and social service agencies.

The role that it plays now is that we never embark in a borough without first doing the assessment, publishing the exegesis and identifying a church network. After publishing the exegesis, we then identify the ‘white space,’ what came out of the exegesis – the things we do not see done in the neighbourhood. We launch our initiative after this.

It is important to do all the steps so as to arrive at a published exegesis of the community. It is not unlike what we see with Nehemiah, Jonah or Paul in Athens – who all do some research before taking action. We have this sense that the Spirit is at work before we get there, and that the Spirit uses his people to begin identifying those things that we ought to be doing. We are now known as an organization that does the hard research.

Lately, we’ve gone a step further. Before we do anything new in one of our boroughs, we will go back to the original research and bring that research up to date before we proceed. We are constantly letting the context inform both what we do and how we do it.

MV: Lately it seems like everyone wants to talk about neighbourhood. Can you comment on this ‘turn’ to the neighbourhood? Why do you think this has become such a popular topic?

GS: Let’s begin by saying that this is not new. The church – whether Catholic or Orthodox or Protestant – was always rooted in neighbourhood, that’s the whole parish system. And this history is not a panacea, the Roman Catholics can teach us about turf wars.

Things changed with the automobile and highway system. What has brought us back has been the forces of globalization. What happens in globalization is that both time and space get squeezed. Here you and I are – we are on Skype three hours different from each other, but time and space becomes meaningless to this conversation. And that’s not a bad thing. It facilitates communication.

But what goes on with globalization theologically is that globalization evacuates transcendence because we control time and we control space. There is no room left for the transcendent. Everything is immanent. Therefore, congregations are working and continue to work hard with how they give a sense of transcendence to people.

And as Christians, incarnation becomes a critical part of the gospel. God becomes flesh. In John 1, God ‘tabernacles’ with us. God becomes present. The struggle here is that far too often in the evangelical tradition, the gospel becomes focused on the immanent and the interior. We don’t engage the neighbourhood because we are so preoccupied with self.

The turn to the neighbourhood reflects the fact that globalization divorces people from where they live, and I think people are becoming fed up with that. We are now beginning to wonder how do we actually live in our neighbourhoods?

Missiologically, congregations are increasingly learning that we compromise the gospel – Jesus is Lord – when we use neighbourhoods. If you buy a building or property and worship in that place and you don’t give back to the neighbourhood, that is to say implicitly that Jesus is not Lord of place.

I think a lot of this turn to the neighbourhood has good theological and missiological roots to it. But I wouldn’t, by any stretch of the imagination, see it as a finished game. I think we constantly need to help people think about this. I’ve been around long enough to see these pendulums go back and forth. We’ve got to help people think about this exegetically, missiologically and theologically.

MV: What advice do you have for church leaders who may want to take place and neighbourhood more seriously? What first steps might they take in terms of research or engagement?

GS: We have a document with 20 steps for churches and church leaders. The 20 steps are practical ways for congregations to begin to participate in neighbourhood transformation.

A couple of points I can make here:

First, we are really big on congregations in a neighbourhood working together to do exegesis. It is an important ecumenical experience, but it is also practical.

Second, churches can attend to history. I’m always struck that churches will have me in because they want to learn about exegesis in the neighbourhood, and they will tell me that they know their neighbourhood. But then I’ll ask them a history question, and they look at me in confusion. I don’t think people understand communities. The first step in the 20 steps is to understand the history. Why do streets look the way they do? Why do neighbourhoods get cut the way they do? All of this is really important to understanding a place. So that is one practical step – to learn history.

Third, congregations can do prayer walks or do more qualitative research by walking the neighbourhood attentively and asking questions. Lots of congregations want to get the socio-demographic data, and so they access it through Statistics Canada, but they often don’t know how to read it or what to do with it. In our 20 steps, the demographics are just one of the steps. We think we can learn the neighbourhood through the numbers, but demographics is only one of the steps.

In the end, the most important thing is to have the congregation move into the neighbourhood and live in the neighbourhood.

MV: What are the big questions that you are working on right now? What are you thinking about and learning?

GS: Three big things:

1. I’m engaged in a big study regarding church planting in Montreal the past 30 years. It’s frightening. I am interested to find out who is going to publish and read this research. I think that church planting has over-promised. The numbers are really quite discouraging. I think we’ve really got to pay attention to that.

2. I think that the ongoing displacement and diffusion of poverty in Canadian cities is going to be a two-edged sword. Twenty years ago if I flew into Vancouver and asked you to show me the poor part of town, you would know where to go. Now, you can take me just about anywhere in the metro area. I think a large part of that is housing policies and what is going on with condos. And that is going to be a mixed blessing because with the rapid aging of the population in Canadian cities, people my age are selling their homes and moving into condos and we are forcing the poor out. They are just going everywhere.

3. I don’t think we can ignore gentrification. Like globalization, gentrification is not unambiguous. But it’s going to have huge implications for the church. We see churches selling the church hall in downtown cores to become a condo, that cannot help but shape the mission of the church. Cities in Canada have become the poor cousins of the confederation. The only way that cities can get money is to tax the air. That is why we have this condo boom going on. Cities need more revenue, so unless we have restructuring regarding how cities are funded in Canada, this condo boom will not go away. And I think this will change the place conversation. What does it mean to have a theology of place when you live in a 20-storey building?