Fr. Matthew Francis with Fr. Daniel (left, Dean of St. Innocent Cathedral) and Fr. Maxim in Alaska.

Creating Conversation is a weekly editorial, curated by the Centre for Missional Leadership (CML), and gives opportunity for people to speak about issues they believe are vital for the church in Vancouver.

One of the goals of this weekly article is to spark dialogue – and action. We invite you to join the dialogue here on the Church for Vancouver website.

We also invite you to use the article as a discussion starter with your small group, church staff, friends and your neighbours. Thanks for participating in the conversation!

A couple of weeks ago, I boarded a plane to Alaska for a meeting of the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative, not fully knowing what to expect.

Does that name ring a bell? Christians in Vancouver may be familiar with the Lausanne Movement, founded in the 1970s by luminaries Billy Graham and John Stott, to promote world mission. Since then, the movement has grown, inspiring leaders – particularly in the global South – to carry out Christ’s Great Commandment of making disciples of all nations.

But what does this have to do with the Orthodox Church, and why did we find ourselves in Alaska, of all places? And what relevance does this have for the Church in and for Vancouver?

‘Unreached’

At the Third Lausanne Congress held in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2010, among the thousands of attendees was His Eminence, Archbishop Angaelos, leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church in London, UK. He also happens to be President of the British Bible Society. He has a reputation as an encourager of Christian youth, and was inspired by what he witnessed at the Lausanne Congress.

Something bewildered him, though. One of the keynote speakers kept referring to traditionally Orthodox Christian majority countries in Eastern Europe and the Middle East as “unreached people groups,” that is to say, groups “unreached” by the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Archbishop Angaelos was born and raised in Egypt – in the Church of the martyrs. He was brought up and served in a Church that has suffered greatly, but is not destroyed. In fact, his own Coptic Orthodox Church in Britain was brimming with spiritual vitality.

This label of being “unreached” did not sit well, and didn’t even make any real sense. The Coptic Orthodox Church had received the Good News of Jesus Christ from the Lord’s own apostles, and had been living out that faith since then.

Instead of simply becoming offended, however, Archbishop Angaelos was moved with courage and love. He didn’t walk out of the Lausanne Congress – he reached out. Coming alongside the leadership, he let them know that it was clear that Orthodox and evangelical believers needed to get to know each other better, to deepen their understanding of each other’s alive and active faith.

Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative

From this moment, the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative was born. In no way was there any intention to diminish the honest theological differences of the traditions, but rather to foster spiritual friendship through mutual study of scripture, and praying for each other.

One stated goal of the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative brings us to the Alaskan experience, from which I gleaned some things that may help us in our own context in Greater Vancouver: “to reflect constructively on the history of relationships between Orthodox and evangelicals, and encouraging reconciliation and healing where wounds exist.”

Three historical points of reference are needed here. They expose some contextual realities between us here in the Lower Mainland of BC and our Alaskan coastal neighbours to the north.

-

- The character of the 18th century mission in Alaska was almost completely unique in the history of world mission.

- The church in Alaska was almost completely Indigenous from the beginning.

- Later historical situations created complex conflicts, damage and wounds that still need healing.

Unique character of mission

The first Christian mission to bring the Gospel to Alaska, in the late 18th century, has numerous characteristics that set it apart from almost all other examples in the history of world missions.

The first Christian mission to bring the Gospel to Alaska, in the late 18th century, has numerous characteristics that set it apart from almost all other examples in the history of world missions.

- The Alaskan Mission is the only major missionary movement to North America that began on the West Coast. All others – typically arriving from Western Europe or the population centres along the East Coast – moved West across the continent, accompanying the colonial powers.

- The Alaskan Mission is the longest missionary journey ever accomplished on foot. The missionaries travelled approximately 6,000 kilometres, from the far northwestern borders of Russia and Finland. Starting in 1793, they walked across all Siberia to the Bering Sea, where they boarded ships and travelled to the Aleutian archipelago, finally arriving at Kodiak in 1794.

- The Alaskan Mission was carried out in ‘the Orthodox way,’ which had always had a principle of using the vernacular languages of the local people in evangelization work. Similarly, if we observe the example of the St. Peter in Acts 10, the apostolic posture of mission begins with listening, as the apostle curiously asked Cornelius about his experience with God, and saw that the Holy Spirit was already present and active. This is the typical missionary ethos of the Orthodox Church, in which prayerful listening precedes proclamation and teaching of the faith.

- The Alaskan Mission was a monastic-led movement. The original group of eight missionaries was sent from Valaam Monastery on Lake Ladoga. Their primarily formation for mission work was the ancient rhythms of prayer, which they had learned in the monastery. The missionaries from Valaam were acquainted with St. Seraphim of Sarov, who provided the well-known aphorism of Orthodox mission: “Acquire the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Peace, and a thousand around you will be saved!” Maybe we should go back and read again Tim Dickau’s recent ‘Creating Conversation’ article on the potential gifts of the new monastic movements in Vancouver.

- The Alaskan Mission embraced all vocations. There were some priest-monks among the eight missionaries who walked from Valaam to Alaska, including St. Juvenaly, who later became one of the first Orthodox martyrs in North America. Nevertheless, the ‘Bright Star’ of the mission was a lay-monk who served as the group’s cook. His name was Herman (1755 – 1837). When the Russian-American Company, which controlled the fur trade, was horribly exploiting the Indigenous people, it was Herman who stood up for them, and became their ardent defender. When all of the other original missionaries either died or returned home, it was Herman who stayed. He nurtured a relationship of respect and love with the Indigenous Aleut people, never ceasing to write letters advocating to the civil authorities on their behalf. In return, they lovingly called him ‘Apa’ (Grandfather), and asked for his prayers.

Alaska: An Indigenous church

Icon of St. Yakov Netsvetov in St. Innocent Cathedral, Anchorage.

From the time of the Valaam mission in 1794, the Orthodox Church in Alaska has been more or less fully Indigenous – among both the faithful and the clergy. One of St. Juvenaly’s companions was an Indigenous leader, whose name has been lost to history. Fr. Yacov Netsvetov, the first Aleut priest, was a renowned evangelist and pastor.

To this day, despite the tragic history of the 19th and 20th centuries in Alaska – when the organic link to their completely Indigenous Christian faith was threatened by the U.S. colonial policies of assimilation and forced ‘Protestantization’ – the Orthodox faithful are still primarily composed of the Indigenous people of Alaska.

On Sunday October 2, I had the blessing to serve with His Grace, Bishop Alexei and local clergy at St. Innocent Cathedral in Anchorage. Twelve priests served with him; nine were Indigenous Yupik priests. This is the norm in Alaska.

I had the experience, as I have elsewhere in the world, of being in a minority. For us as settlers on these lands, this is a critically important experience, which I will carry with me in my heart.

The Divine Liturgy was served largely in the Yupik language, and the traditional Orthodox hymns of the Resurrection were sung with great spiritual fervor in Yupik. It was awe-inspiring to witness, and to be present.

Need for truth & reconciliation in Christ

The unique character of the historic, Orthodox Christian mission to Alaska, and the accompanying experience of Indigenous Alaskan Christian spirituality, has not been immune to the brutal realities of the past 200 years.

The unique character of the historic, Orthodox Christian mission to Alaska, and the accompanying experience of Indigenous Alaskan Christian spirituality, has not been immune to the brutal realities of the past 200 years.

After the sale of Alaskan sovereignty to the United States in 1867, much changed, and racist policies such as the implementation of residential schools – similar to what we know in Canada – happened there also. In some cases, children were trafficked by the government down to the ‘Lower 48’ for residential school.

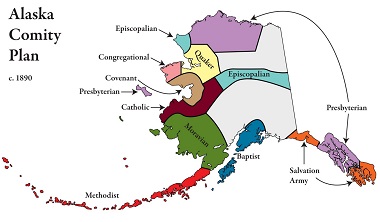

Areas that were completely Indigenous and Orthodox Christian were divided up among the other various Christian denominations to adopt a faith that was more familiar and congenial to ‘American’ values. Notably missing is the Orthodox Christian faith, which was constrained and marginalized for its association with Russia, as a colonial competitor to U.S. interests.

The resulting experience through the 20th century has been one in which largely ‘evangelical’ Christian missionary agencies have sought to carry out their work in many of the largely Indigenous villages of Alaska.

Most of these have been completely Orthodox for over 200 years, despite the ‘Comity Plan.’ Entrenched misunderstanding and bitter jealousy have sadly most often carried the day. Much false witness has been borne by committed believers from both traditions, and sadly Alaska remains rife with this tension.

Turning point?

I believe the meeting of the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative, held in Alaska just a few weeks ago, may prove to be a turning point.

Fr. Michael Oleksa, author of Alaskan Missionary Spirituality, said it well when he pointed out that the minimum we can do is to stop bearing false witness against each other.

Leaders from prominent mission organizations, as well as Orthodox faithful and clergy, had the opportunity to get to know each other, and to explore together our painful, yet shared history.

Honest words of repentance – offered spontaneously and from the heart, were given and received. Prayers were offered for each other and with each other. Spiritual friendship provided a context for healing, and a better understanding of our common witness for Jesus Christ.

I continue to process my time in Alaska, and to be encouraged by my new Alaskan friends. I hope that the faith I witnessed there will inspire me to deeper and more authentic relationships, within the Church for Vancouver.

Father Matthew Francis is the founding priest of the Holy Apostles Orthodox Mission in Chilliwack. He also serves as Regional Director for BC & Yukon with the Canadian Bible Society.

A November 10 article on the Lausanne Movement site was titled ‘Evangelicals and Orthodox Christians taking hands: The Story of the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative.’

Thank you for this beautiful testimony of God’s goodness and faithfulness. Whether they are huge steps, or faint glimmers, every act of respect and love for our fellow humans, every act of truly loving our neighbour, is a great encouragement. God is on the move! It is a privilege to work with you in the Canadian Bible Society.

Thank you Father Matthew for this highly inspiring and informative article on the history of Alaskan missions, how fascinating!

For decades, I have wondered what would have happened if our missions posture in North America would have been one of learners and listeners in order to be aware of how God was already at work amongst Indigenous communities. Surely we would have been more faithful to resist the pressure to align ourselves with the agenda of colonization and the attempted cultural genocide that occurred through residential schools.

It seems that learning and listening was the posture of Orthodox missions in Alaska, resulting in empowering Indigenous leadership and and encouraging Indigenous expressions of faith. How sad that other denominations did not have the generosity of heart to honour and recognize this. The Lausanne-Orthodox initiative is a hopeful sign that this is changing.

Thanks for this informative and inspiring account. I have visited Orthodox Church buildings in Alaska and elsewhere – including the Middle East and have always come away with a renewed sense of God’s presence in Jesus among us.

Our Anglican Church in Gibsons BC – St. Bartholomew’s – hosted the gatherings of the Orthodox community in Gibsons before COVID. We certainly hope at some point they return to us and continue to bring life to our Bethlehem Chapel worship space.

Thank you for sharing! Glory to God!