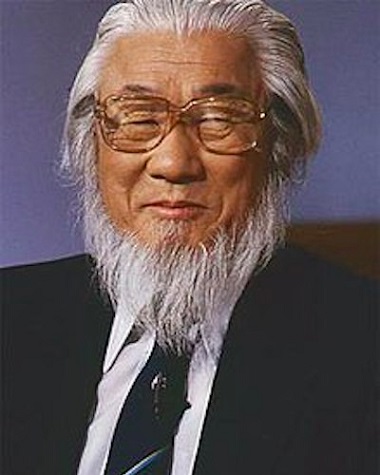

Sang Chul Lee came from South Korea to minister at Steveston United Church.

Korea has a very strong church presence and is now a major missionary force around the world. But the church is also very young, and missionaries from Canada played a significant part in introducing the gospel to the East Asian nation.

An online book launch next Monday (October 3) will look at that relationship. David Kim-Cragg will introduce Water from Dragon’s Well: The History of a Korean-Canadian Church Relationship (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022).

There are several good reasons to take note of this book.

Missionary heritage

Kim-Cragg says his church has almost entirely lost track of its missionary heritage.

After going to South Korea as an exchange student at Hanshin Theological Seminary, he was on hand when the United Church of Canada (UCC) and the Presbyterian Church in the Republic of Korea (PROK) celebrated 100 years since the establishment of mission there.

He said:

When I first arrived in Korea, I was taken by stories I learned from Koreans about Canadian missionaries, particularly their role in the South Korean Democratization Movement. . . . .

The stories I heard at that time were stories I had not heard before despite my close association with the UCC since birth. I wondered why I had not been aware of these things in Canada. After all, the stories were overwhelmingly positive and I could think of no reason why they were not being shouted from the rooftops back home.

He learned that Canadian public opinion had largely shifted away from supporting missionaries, often lumping them in with the increasingly discredited colonial enterprise:

With this shift in the culture, stories about missionaries and their exploits in Canada and overseas began to focus on the negative implications of missions for non-Western nations and peoples. . . . .

Kim-Cragg decided to deepen his understanding of Korean-Canadian church relations.

Leading the way

Missionaries who had long experience in Korea had learned that it was best not to impose their cultural perspectives on Koreans:

Missionaries who had long experience in Korea had learned that it was best not to impose their cultural perspectives on Koreans:

The irony here is that by the 1960s many missionaries [though not their home churches] had effectively absorbed the criticism of indigenous Christians overseas with whom they worked and were actually on the leading edge of attitudinal change.

What is more, they were qualified from years of close work with non-Westerners to offer guidance to the rest of the Canadian church and society as it began to navigate its way into a new postcolonial context.

Books such as Protestants Abroad and Claws of the Panda: Beijing’s Campaign of Influence and Intimidation in Canada describe such a phenomenon among missionaries from other nations as well.

In Claws of the Panda, Jonathan Manthorpe said:

Thus, the missionaries and their offspring, brought up in China, fluent in the language and cultures – the so-called Mish Kids – were instrumental in shaping public support for the early recognition of the People’s Republic of China after the Communist Party took power in 1949.

Sympathy for the CCP among the Mish Kids stemmed from two sources: antipathy toward the neo-fascist Kuomintang and politically left of centre interpretations of Christianity among Methodists and the United Church of Canada.

The Mish Kids and other scions of the Methodists, in particular, had a significant presence in the Department of External Affairs in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. They also played major roles in the evolution of Canada’s independent foreign policy after the Second World War.

(I posted “Claws of the Panda: the curious role of ‘Mish Kids’ in Canada’s China Policy” on Church for Vancouver.)

Korean missions are particularly important in Canadian history because they lasted longer than those in locations such as China and India, which expelled most elements of Western colonial power.

As well, the indigenous church was particularly strong in Korea. In time, Koreans came to have significant role in the United Church of Canada – and have planted many churches in Canada, including scores (most not connected to the UCC) in Metro Vancouver.

Local connection

Kim-Cragg said “the main objective of [Water from Dragon’s Well ] is to present the history of Korean Christians’ engagement with the United Church of Canada and its Presbyterian tributary, and the changes in both Korean and Canadian Christianity that were the result.

A key player in Canada was Sang Chul Lee, who spent four years as pastor of Steveston United Church in the 1960s before moving back east and eventually becoming Moderator of the United Church of Canada:

Lee reports having felt ambivalent about the call. His father-in-law [Kim Chai Choon, a PROK leader] . . . encouraged him to accept the invitation, however, telling Lee that after so many years of missionaries coming to Korea, it was time for something different: it was Lee’s turn to be “a Korean missionary to Canada.”

Coincidentally, Lee’s return to Canada occurred just ahead of the first wave of Korean immigration into the country. . . . [In] 1965, a steady stream began to flow through the Vancouver airport. As a result, in 1966, while still serving the English and Japanese congregations, Lee found himself responsible for an additional congregation of Koreans which met at the Union Theological Seminary (currently the Vancouver School of Theology) on the University of British Columbia campus.

Though many who arrived were not baptized, Lee’s main objective was not to make new Christians. Lee was motivated, rather, by a need to provide a supportive community for the new immigrants.

Lee’s sense of identity had deep roots, nurtured in a chaotic situation:

Born on the kitchen floor in a peasant’s home near Vladivostok, Russia, Sang Chul Lee, the son of Korean refugees, was destined to live a migrant’s life. In his English autobiography, entitled The Wanderer, Lee shares the story of his family’s flight from Siberia to Manchuria when he was a child, then his flight from Manchuria to South Korea at the conclusion of the Pacific War, and finally his voluntary migration across the Pacific to Canada. . . .

Lee nevertheless had two constants in his adult life that anchored his sense of self.

The first was a sense of nationalism as it applied not only to the Korean community into which he had been born, but also in a more broad sense of a commitment to the well-being of the community in which he found himself, a commitment that often meant opposition to larger transnational forces such as colonialism and international Cold War hegemonies that threatened these communities.

The second constant since the time Lee was a teenager attending a UCC-run mission school in Manchuria was a devotion to the Christian faith. Christianity, as he understood it, not only unlocked deep springs of spiritual power but also encouraged a sense of national commitment.

Lee’s arrival in Canada, then, was marked by the sense that he had something to contribute to his new nation and church.

Following his time in Richmond, Lee focused on social justice issues while pastoring a church in Toronto. In 1988 he was voted Moderator of the United Church of Canada.

Korean immigrants

In the book’s Conclusion, Kim-Cragg states:

The development of Korean Christianity had a significant impact on the UCC and the Canadian religious landscape. The impact cannot be fully understood outside the history of the Canadian Missionary Enterprise.

Rather than empty vessels that allowed themselves to be filled with the water of Anglo Protestant ideas and culture, Koreans who came into contact with Canadian missionaries were pioneers who filled the furrows of their newly plowed fields with waters from their own wells of history, philosophy, religion and politics. . . .

[W]ith regard to the function of Christianity in preserving a distinct Korean culture, just as the early Korean congregations had done in Korea, Korean Christian communities in Canada used the church as a way to preserve and promote their culture and language in a strange land.

Clear focus

Kim-Cragg subtitled his books as ‘The History of a Korean-Canadian Church Relationship.’ The a is important. This is by no means a history of all missionary activity in Korea. Pentecostals, Evangelicals, Baptists, Roman Catholics, Anglicans – not covered.

The many Korean church all over Metro Vancouver, and many other big cities are not featured. Nor is there any talk about the well known fact that the Korean missionary force is now the second largest in the world.

Water from Dragon’s Well still covers a lot of ground, especially in terms of United Church / (some) Presbyterian / progressive interaction between Koreans and Canadians. The upcoming book launch should be well worth attending (online). Much more attention should be paid to our missionary heritage.