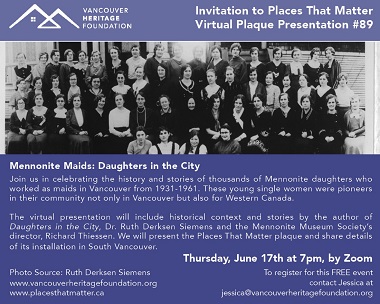

The Vancouver Heritage Foundation will host a ‘Places that Matter Virtual Plaque Presentation’ June 17 to celebrate the history and stories of thousands of Mennonite daughters who worked as maids in Vancouver between 1931 and 1961.

The Vancouver Heritage Foundation will host a ‘Places that Matter Virtual Plaque Presentation’ June 17 to celebrate the history and stories of thousands of Mennonite daughters who worked as maids in Vancouver between 1931 and 1961.

The virtual presentation will include historical context and stories by the author of Daughters in the City Ruth Derksen Siemens and the Mennonite Museum Society’s director Richard Thiessen.

Who are these Mennonite maids? These daughters in the city? Where are they from? Why are they working in Vancouver? Why does a Mennonite minister send this dire warning?:

May the hour soon come when none of our people can be found in Vancouver, or any other large city . . . Unfortunately, I must report some shadows, some stumbling and falling. Two of our young girls have fallen as deep as a girl can fall. The slippery sheet of temptations in a large city is treacherous, especially when it is a port city.

I cannot refrain from pleading with parents, “Don’t send your daughters to the city unless you are in dire straits”. I do not commend parents from Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta who send their daughters to work in Vancouver because of higher wages . . .

The dangers are increased by the lack of moral standards in a harbour city. At the same time, family ties are weakened by prolonged absence. . . . (Rev. Jacob Thiessen, Protocol, November 1942).

Yet in spite of this warning, young women continued to leave their parents, extended families and communities. From historical records and personal accounts, it is clear that hundreds of young immigrant Mennonite women came to Vancouver beginning in the late 1920s and into the 1960s.

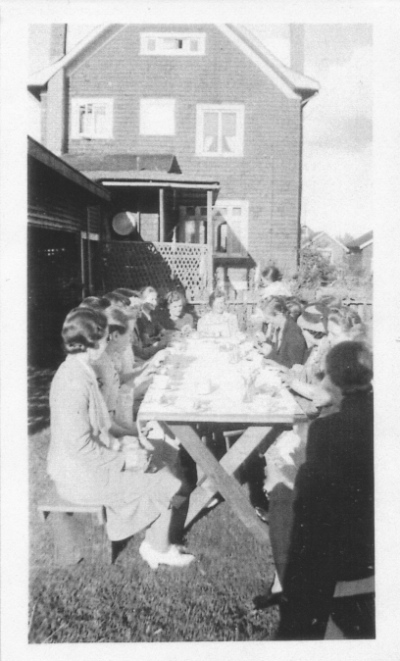

Backyard Sunday supper at the Bethel Home (6363 Windsor Street)

They were maids (domestic workers) employed in homes of upper-class families. Many were adolescents – some as young as 14.

Initially upon their arrival, they slept on benches in the train station, or rented a cheap hotel room or a boarding house room until they found live-in employment through newspaper ads.

The first group of girls and their families had arrived as refugees from Russia in the 1920s, escaping the terror of Stalin’s regime.

The financial burden on their parents was severe – to pay the Travel Debt to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) for their transport to Canada.

Everyone who was able worked. Besides working as maids in Vancouver, they worked in hop yards, grain fields, raspberry farms, processing plants, factories and sawmills.

A second group arrived after World War II, having endured the trauma of the war in both Russia and Europe. Some had sponsors or relatives in Canada to depend on, but others had few connections. Some had been orphaned in Russia.

These young women were members of an immigrant ethnic minority who had few of the material assets needed to survive in a foreign country.

Facing language challenges, cultural barriers and loneliness, these young women together with the church established two Girls’ Homes: Bethel Home (Mennonite Brethren) and Mary Martha Home (Mennonite Church Canada).

Matron Tina Lehn (centre front) at the Mary Martha Home (6460 St. George Street).

Through interviews, minutes of meetings, photographs and other publications, the reality of everyday life for these young women has emerged.

They have shared stories about exotic British food, bridge parties, ladies “who stayed in their housecoats until noon” and ate dinner at 8 pm. They have talked about their employers’ expensive clothing, boxes of castoffs and the misery of English children who had too many toys. But they have also been proud of their superior ways of washing a floor, whitening the laundry and starching a shirt.

There were inevitable embarrassments too – English language use (confusing ‘kitchen’ and ‘chicken’), learning telephone rituals, understanding laundry requests and using furniture polish. But there has also been silence. Much has been said by not saying.

That the young immigrant women were vulnerable and exposed to unsafe working conditions is without dispute. The matrons of the Girls’ Homes appeared to have been very aware of the hazards the young women faced. These caretakers were fiercely protective over their wards’ welfare.

A large wall map at the Mary Martha Home guides Helen Rempel to her employer’s house.

Employees in domestic service often worked 15 hours a day. But though the work was strenuous, repetitive and often lonely, the young women found time to explore the city.

Enforced by the matrons, Sundays and Thursday afternoons were the ‘maids’ day off.’. They gathered for games and bag lunches at the Girls’ Home, rode the streetcar all over the city, watched the rowboats at Lost Lagoon, or had picnics in Stanley Park.

Most talked about the “oasis” and “refuge” experienced when speaking their own language, sharing ethnic food and telling stories of their week.

There is no doubt that the two Mennonite Girls’ Homes (Mӓdchenheime) of Vancouver shaped the attitudes, settlement patterns and class distinctions of these young women. But significantly, they also influenced their families, communities and the generations that followed. They deserve to be remembered.

The website www.daughtersinthecity.com offers further information and details about ordering the book, Daughters in the City: Mennonite Maids in Vancouver, 1931-61.

Ruth Derksen Siemens is a first-generation Canadian of Russian Mennonite descent who was born in Vancouver and has also lived in a traditional Mennonite community in the Fraser Valley. She is an Emeritus instructor of writing and rhetoric at UBC.

Her PhD in the philosophy of language (University of Sheffield, UK) investigates a corpus of 463 letters written by Russian Mennonites from the former Soviet Union. Some of these letters appear in her edited work. Remember Us: Letters from Stalin’s Gulag (1930-37) and the documentary film Through the Red Gate (YouTube).