Isobel and John Kuhn spent a quarter of a century with the Lisu people.

China is sparing no expense or inconvenience as it prepares to welcome the world for the Winter Olympics in February. But Xi Jinping’s increasingly aggressive regime is much less receptive to international movements which are less directly under its control.

Thus, the persecution of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Controls on churches have been tightened, and many Christians workers from abroad have been forced out of the country.

Despite that climate of distrust, many Chinese Christians remember and appreciate the missionaries who brought the Christian faith to their nation. A surprising number of those missionaries were Canadian and had close ties with Vancouver.

The following stories are focused especially on the southwest of China:

* Chinese pilgrims recently visited sites of early missionaries (including Isobel Kuhn) among the Lisu people in Yunnan, just north of Myanmar and Laos.

* Aminta Arrington’s Songs of the Lisu Hills (2020) focuses on how the Lisu have indigenized Christianity.

* Chinese human rights writer Liao Yiwu dedicated God is Red (2011) to the memory of missionaries (including Dr. Jessie McDonald) in Yunnan.

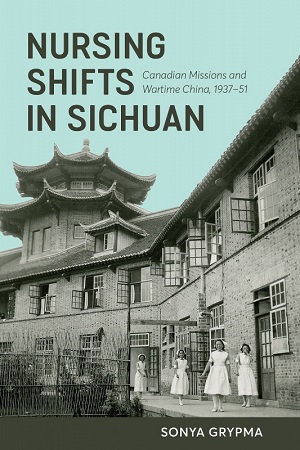

* TWU professor Sonya Grypma’s brand new book, Nursing Shifts in Sichuan (Sichuan, now Szechuan, is just north of Yunnan) examines the important role of the Canadian West China Mission in Chinese medical history.

Visiting the Lisu

A recent article describes the lengths to which some Chinese Christians have gone in order to pay homage to missionaries from the West. The article, originally from We Jinglie, was presented on the ChinaSource site in two installments.

A recent article describes the lengths to which some Chinese Christians have gone in order to pay homage to missionaries from the West. The article, originally from We Jinglie, was presented on the ChinaSource site in two installments.

It was introduced in this way:

Nine Christians from several cities in China traveled to Nujiang, Yunnan Province to find the places where early foreign Christians proclaimed the gospel among the Lisu.

During the trip they met people who knew those early workers and were impacted personally by their conversations and simply being in those places. The faith of those early workers and those still serving continues to speak to us today.

The article began with this quote and response:

I wish I could get home right away and stay in my quiet bedroom next to the deep valley. The birds sing their morning song early, joyfully and clear. The sunset glows behind clouds at evening, and the towering peaks as well, all contributing to a wonderful and glorious view.

Isobel Kuhn and her first girls’ Bible school. OMF International image

When I read this passage written 80 years ago by American missionary Isobel Kuhn, I was moved by her picturesque life.

However, when we traveled almost halfway across China, dragging our exhausted bodies, breaking through layers of pandemic barriers, and finally arrived in front of this dilapidated hut, everything seemed totally different than we expected.

The small wooden hut was a dozen or so square meters in size. The roof was covered with gray tiles. It was very dark inside and the only furniture included a small desk by the wall, a short cabinet, and several farm tools we could not identify. Even so, we still felt that it was worth the trip.

Isobel Kuhn was Canadian, raised in Vancouver, rather than American, but it is not surprising that the author was mistaken about where she came from. Her husband John was American; she met him while training at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago.

Began in Vancouver

Isobel Miller grew up in Vancouver.

Isobel Kuhn’s quarter century of service with the Lisu people of southwest China and Thailand (1928 – 1954) with China Inland Mission was hardly a foregone conclusion.

The Wheaton College Billy Graham Center Archives posted ‘Letters from Lisuland: The Ministry of Isobel Kuhn’ last spring. After referring to her graduation from UBC with an honours degree in English language and literature, the article noted:

Her university studies marked a turning point in Isobel’s spiritual life. Though she had been raised in a devout Christian home, Belle struggled with spiritual doubt during her years as a student, becoming a self-professed agnostic.

In her autobiography, By Searching: My Journey through Doubt into Faith (1959), Belle recounted how a broken engagement and thoughts of suicide provoked a spiritual crisis, resolved only by submitting her life to God’s will.

Following graduation, Belle intended to pursue her talent for writing into an academic career at the college level. But her aspirations shifted again after meeting J.O. Fraser, a celebrated missionary to the Lisu people of southwest China, at a summer Bible conference in 1924 [at The Firs in Bellingham], and her imagination was captured by the vision of spreading the Christian gospel among the marginalized Lisu people in the remote interior province of Yunnan.

Isobel sailed from Vancouver October 11, 1928, and married John Kuhn in Kunming, China just over a year later.

With the Lisu

Isobel Kuhn with her daughter Kathryn and local women.

From 1929 to 1950, the Kuhns and their children served at several China Inland Mission (now Overseas Missionary Fellowship) stations across Yunnan (though the children were often separated from them).

Their work was well known to earlier generations, in large part because Isobel wrote nine books.

By Searching tells how she became a missionary, beginning with her youth in Vancouver. In the Arena surveys their life in China.

There were plenty of trials and potential dangers along the way. For example, the Archives have a note from May 8, 1936 which records the incursions of Communist forces. Fellow missionaries were forced from their various homes and a number of them gathered in the nearby town of Tali (Dali), before they were all forced to evacuate for a period of time.

The Kuhns were able to return to their work before too long, but they were forced out of China after the Communists took power in 1949. They returned to the States temporarily, but went back to work with the Lisu in Thailand in 1952. When Isobel was diagnosed with cancer in 1954 they returned home again, and she died in 1957.

Standing guard

The Lisu remember and treasure the legacy of the early missionaries – and their culture has been transformed through that legacy. At least half of the 600,000 Lisu now living in China consider themselves Christian.

The ChinaSource writer described what the pilgrims found:

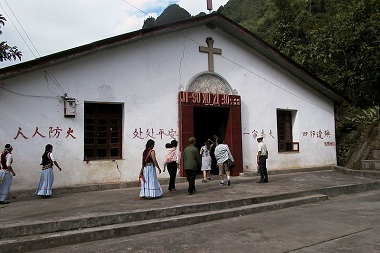

Lisu Church in Fugong (福贡), Yunnan Province, China. Author Gerard Willemsen. (Creative Commons)

It was truly God’s grace! Later, underneath white clouds and a beautiful blue sky, we drove to a church in that village. The church was located by the side of a hill, with whitewashed walls and a gray tiled roof.

Because of the pandemic, the door of the church was locked. To the left and right of the church were two large, lush trees planted by the Kuhns 80 years ago.

Beside the tree Mrs. Kuhn planted stood the Bible school; below the hill on which Mr. Kuhn’s tree stood was the hut where they had lived for 13 years.

Next to the Kuhns’ hut lived an old woman with her family. This 84-year-old woman is a follower of Jesus and welcomed us warmly when we tried to take photos of the hut. She married into this village in the 1950s. When the Kuhns left in December of 1948, she led her family to repair the outside part of the hut, while the objects inside remained untouched. She then guarded this hut for more than 60 years.

Standing on the hillside and overlooking the whole of Nujiang, which was the center of evangelization back then, we could almost see the honest and illiterate mountain people who came here, climbing over the mountains during the rainy season to study the Bible eagerly. As the Bible says: “The unfolding of your words gives light; it imparts understanding to the simple” (Psalm 119:130). And then those groups of people brought the gospel to homes in every corner of Nujiang.

But the missionaries’ faith took on a new form among the Lisu.

Lisu faith

Aminta Arrington says in her new book, that “I first heard about the Lisu when I picked up a worn copy of Isobel Kuhn’s spiritual autobiography, By Searching.”

Aminta Arrington says in her new book, that “I first heard about the Lisu when I picked up a worn copy of Isobel Kuhn’s spiritual autobiography, By Searching.”

Songs of the Lisu Hills: Practicing Christianity in Southwest China (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020) shows how seriously she has followed up on that chance encounter. The book is interspersed with references to Isobel Kuhn, as well as to John and to other missionaries have been so influential among the Lisu.

The book jacket notes:

The story of how the Lisu of southwest China were evangelized 100 years ago by the China Inland Mission is a familiar one in mission circles. The subsequent history of the Lisu church, however, is much less well known.

Songs of the Lisu Hills brings this history up to date, recounting the unlikely story of how the Lisu maintained their faith through 22 years of government persecution and illuminating how Lisu Christians transformed the text-based religion brought by the missionaries into a faith centered around an embodied set of Christian practices.

Brian Stanley, Professor of World Christianity at the University of Edinburgh, said in the Foreword to the very current Songs of the Lisu Hills:

John Kuhn leading a Bible study. OMF International image

Today, the Lisu hymnbook is a constant companion of the Bible in the hands of Lisu Christians. . . . Lisu piety is recognizably evangelical – many of the hymns they sing are radically indigenized versions of Western evangelical classics – and yet the Lisu Bible is not so much read, as orally performed in public worship, and also venerated as an object carried to church in brightly embroidered Bible bags.

Isobel Kuhn described such practices in Nests Above the Abyss (1947):

A day or so before the birthday of Christ, every Christian Lisu village is making its preparations to send a contingent, young and old, everyone who can go, to the Christmas celebration. . . as soon as the village slope is sighted, they come upon a floral arch with smiling faces peeking at them from underneath. Here they must halt while the other side tunes up.

“One-three-five (doh-me-soh)” sings out the leader of the reception committee, “Let it come!” And voices in four parts rise up from behind the flowers:

Christmas guests are at the door!

Let them in.

It is duty to receive them,

Let them in.

That of Jesus we may think,

His Great Day that we may keep;

Praise to God, we come to greet.

Let them in!

(Tune: There’s a Stranger at the Door)

Then through the arch they come, shaking hands with each of the long line of singers . . .

Arrington gives due credit to the missionaries, but also to the Lisu:

The Lisu church can be considered a missionary church, true to the roots planted by J.O. Fraser, The Cookes, the Kuhns, the Morse family and many other Lisu church elders and deacons. But at the same time, it is a post-1980 church . . . .

The initial evangelization of the Lisu happened at the missionaries’ behest and initiative. But the revitalization of Lisu Christianity, after more than two decades of dormancy, was an almost entirely Lisu project.

Many other missionaries worked, and are remembered for their work, in southwestern China.

God is Red

Several years ago a book from an unlikely source echoed the outlook in the ChinaSource article. Though not a believer himself, respected civil rights author Liao Yiwu wrote God is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived and Flourished in Communist China, about other Indigenous believers in Yunnan, just south of Sichuan.

Several years ago a book from an unlikely source echoed the outlook in the ChinaSource article. Though not a believer himself, respected civil rights author Liao Yiwu wrote God is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived and Flourished in Communist China, about other Indigenous believers in Yunnan, just south of Sichuan.

In the words of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize Winner Liu Xiaobo:

In his book, Liao wanders in those forgotten villages in the southwestern part of China and explores a spiritual world neglected by modern civilization . . . Liao’s coverage of Christians allows truth to shine in the darkness.

I wrote about the book in 2013:

Local people told him that the China Inland Mission had sent missionaries to Shanghai 150 years ago, and that they had quickly travelled to the furthest corners of China. “These foreigners, ‘with blond hair and big noses,’ [arrived] . . . just in time to save the people from a bubonic epidemic.” Liao, who had grown up in an era when missionaries were portrayed as ‘evil agents of the imperialists,’ was surprised by such stories.

“Three or four generations later,” Liao said, “Christianity was part of the heritage of each individual family and an integral part of local history . . . in the Yi and Miao villages, Christianity is now as indigenous as qiaoba, a special Yi buckwheat cake.”

But at a great price. “The circuitous mountain path in Yunnan province is red because over many years it has been soaked in blood.” His appreciation of the missionaries and his interviews with old pastors, nuns and lay people, in which their long-suffering hope for the future is so apparent, lie at the heart of this moving book.

“I was struck by the dedication of the missionaries,” Liao says. Dr. Jessie McDonald (born in Vancouver) arrived in China in 1913, and worked at a hospital in Kaifeng. When the Japanese took over that city, she moved the hospital to Dali, in Yunnan. She carried on until Communist officials seized the hospital and forced her out of China in 1951.

Go here for the full article.

Liao Yiwu dedicated his book “to the memory of those who lived and preached in Yunnan,” adding a list of more than 60 missionaries.

Nursing Shifts in Sichuan

Trinity Western professor Sonya Grypma has just completed a book about the area and time under discussion – Nursing Shifts in Sichuan: Canadian Missions in Wartime China, 1937 – 1951. Published by UBC Press in December, the book note describes the significance of its topic:

Trinity Western professor Sonya Grypma has just completed a book about the area and time under discussion – Nursing Shifts in Sichuan: Canadian Missions in Wartime China, 1937 – 1951. Published by UBC Press in December, the book note describes the significance of its topic:

Nursing Shifts in Sichuan illuminates modern nursing as one of the most consequential additions to early 20th century health care in China. In 1943, members of the elite Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) were forced to evacuate to the ‘backwater’ province of Sichuan, landing at the West China Union University campus in Chengdu.

As part of an extraordinary mass migration of students and professors to Free China during the Japanese occupation, the refugee PUMC was hosted by the Canadian West China Mission for the next three years. . . .

In the contemporary era of exponential increases in East–West educational exchanges, Sonya Grypma offers both a cautionary tale about the fragility of transnational relations and a testament to the resilience of educated women.

This is Grypma’s second book on this theme; she also wrote Healing Henan: Canadian Nurses at the North China Mission, 1888 – 1947.

In 2020 I posted ‘China’s top coronavirus-fighting hospitals have missionary roots.’ One of the four is West China Hospital, SIchuan University. My article was based on a piece in China Christian Daily, which stated:

In 2020 I posted ‘China’s top coronavirus-fighting hospitals have missionary roots.’ One of the four is West China Hospital, SIchuan University. My article was based on a piece in China Christian Daily, which stated:

The West China Hospital grew out of the Renji Hospital and Cunren Hospital which were founded in Chengdu by churches from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and other countries in 1892. The West China Union University’s medical college began operations in 1914, following the model of medical education in the West.

Go here for my article, which mainly focuses on a book about Dr. Thomas Cochrane and his amazing story, including his role in founding Peking Union Medical College Hospital, and here for the China Christian Daily article.

Still undervalued

The ChinaSource article concludes with these words:

When we left Apu’s home, it was time to wrap up our trip. Though we had come to trace the footsteps of past missionaries, as we got ready to leave, we realized that we ought to be paying more attention to the living preachers.

We show much reverence to the missionaries who have passed away, yet too often ignore those preachers who are not well-educated or skilled in speaking but have humble hearts and persevere in the poor countryside to show God’s love. Therefore, we established a fund to support them out of our meager strength.

These are good words to remember in Vancouver as well. It is so easy to overlook the hard work of those right around us.

However, I still wonder, where are the Isobel Kuhn books in our church libraries, the references by pastors to daring missionaries? The recognition of how much suffering has been endured by those who adopted the ‘western’ religion? The ongoing solidarity with those who continue to live out their faith under persecution?

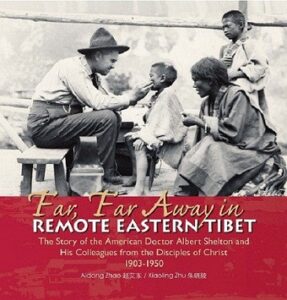

Shelton Memorial Christian Church

This book chronicles the work of Dr. Albert Shelton and his fellow missionaries.

One memorial which has now disappeared from Vancouver is the Shelton Memorial Christian Church.

Last summer the host of Vancouver As It Was posted an interesting story about a church which came and went in the first half of last century.

Go here for the story and images (the site is well worth checking out in general), but what ties the church to this story is that it was named after another pioneer missionary in southwest China and Tibet.

Dr. Albert Shelton was a missionary from 1903 until 1922, when he was shot and killed by brigands while traveling by mule near Batang, now on the very western border of Sichuan. He, along with J.O. Fraser, were missionaries to whom Isobel Kuhn looked as she considered devoting her life to China.

The man died just under 100 years ago; I wonder if he is better remembered in southwestern China and Tibet than anywhere in North America.

What happened to Kathryn and Daniel Kuhn?

I am just re-reading the three books by Isobel Kuhn (probably the fourth time). I cannot put them down! They (the faith lessons) are so relevant for today’s world and church. Yes, we need to be and find more people who say “God First!” Now I’m going back to the story of Hudson Taylor!

Thank you so much for this inspiring article chronicling the high regard still held by many Chinese citizens for pioneers of the m. endeavor in China in the first half of the 20th century. It was specially interesting to learn more detail about the impact of Isobel (Miller) Kuhn among the Lisu people in the far west of Yunnan province.

As a university teacher for many years of the human geography of China, I have been to China over 40 times, often with an emphasis on Yunnan and Guizhou provinces in the southwest where the Kuhns and others mentioned lived the Good News so faithfully and effectively. What a legacy! My parents served mostly in northwestern China before continuing in Taiwan after 1950.

Thank you Peter. What a heritage indeed.

I posted an article about Peter Foggin and his family’s strong and enduring connection with East Asia:

https://churchforvancouver.ca/peter-foggin-born-in-china-his-love-for-asia-has-remained-strong/

Flyn,

Thank you for this inspiring article about missionaries to China, especially about Isobel Miller from Vancouver and her journey of faith. Am eager now to read her autobiography and also to learn more of the Lisu Christians and their story.

Thanks for keeping Church for Vancouver going !

Dan Gowe